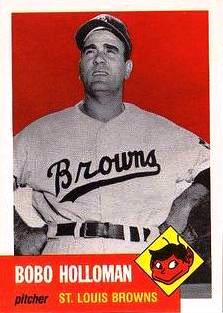

Bobo Holloman

Who was the first major-league pitcher in the modern era to throw a no-hitter in his first start? The answer is the St. Louis Browns’ big right-hander, Alva Lee “Bobo” Holloman. “Improbable” was the adjective most often used to describe Holloman’s gem of May 6, 1953 — and its odd distinction would come to stand out more. As is always recounted, that was the only complete game Bobo pitched in his short career — he was out of the majors before the end of the 1953 season with only three victories to his name.1

Who was the first major-league pitcher in the modern era to throw a no-hitter in his first start? The answer is the St. Louis Browns’ big right-hander, Alva Lee “Bobo” Holloman. “Improbable” was the adjective most often used to describe Holloman’s gem of May 6, 1953 — and its odd distinction would come to stand out more. As is always recounted, that was the only complete game Bobo pitched in his short career — he was out of the majors before the end of the 1953 season with only three victories to his name.1

More than six decades passed before any other pitcher matched Holloman’s feat, until Tyler Gilbert of the Arizona Diamondbacks threw a no-hitter against the San Diego Padres in 2021 in his first start and fourth career appearance. Holloman was only the eighth rookie since 1900 to throw a no-hitter2, and from then on, the newspapers have told the tale of “Bobo’s No-No.”

Some will qualify Holloman’s feat, noting that two other men before him pitched no-hitters in their first big-league start. However, they came before 1893, the year in which the pitching mound was moved back to its current location, 60 feet, 6 inches from home plate. On October 4, 1891, 22-year-old Theodore Breitenstein of the St. Louis Browns in the old American Association allowed no hits in an 8-0 win over the Louisville Colonels. Just over one year later, on October 15, 1892, 22-year-old Charley “Bumpus” Jones pitched a no-hitter in his major-league debut as the Cincinnati Reds defeated the Pittsburgh Pirates, 7-1.3

Alva Lee Holloman Jr., was born in Thomaston, Georgia, to Alva Lee Sr. and Hattie Holloman on March 7, 1923.4 Alva Lee was the fourth of six children — Edward, Baynard, Connie, Alva, Richard, and Carol — and he soon came to be called “Junior.”

As a boy, Junior helped his father, a truck farmer. In fact, amid the Great Depression, he was forced to quit high school after just one year. Father and son hauled sweet potatoes and watermelons to Florida and brought oranges back to Georgia.

In 1940, the Hollomans moved about 100 miles northeast to Athens, Georgia. There Junior met Nan Stevens, daughter of Jessie and Maxine Stevens. Nan recalls the Sunday night “that good-looking, coal-black haired, brown-eyed ‘new’ boy in town” gave her a ride home from the Mars Hill Baptist Church.5 They were married on January 24, 1942. Holloman served in the United States Navy, and early in their marriage he was stationed at Port Hueneme near Oxnard, California. He then shipped overseas for 11 months until his discharge in December 1945.

Holloman played sandlot baseball as a youth; while at Port Hueneme, he pitched for the base’s team. Back at home in 1946, he tried out for the Macon Peaches, a Class-A baseball team affiliated with the Chicago Cubs in the “Sally” (i.e., South Atlantic) League. The team liked what they saw in the 6-feet-2, 200-pound hard-throwing right-hander, and assigned him to the Moultrie Packers, a Class-D team in the Georgia-Florida League. There he enjoyed an all-star season, striking out 184 batters in 216 innings and compiling a 20-5 record with a 2.33 ERA for his favorite manager, Jim Poole. At one point, he pitched a doubleheader to make up a turn, so he could come home for the birth of his son, Gary Lee, on July 4, 1946. Six weeks later, young Gary, nicknamed “Little Papoose” since his papa was “Big Indian Chief” to the Moultrie fans, witnessed his first baseball game. The Big Chief pitched and won and hit a home run.

That winter, Holloman pitched in Cuba with the Oriente team in La Liga de la Federación (an “alternate” league that existed for one season in the wake of the Mexican League’s player raids). It was not an especially successful season, as he lost a league-leading six games in a brief 40-game schedule.6 Back in the United States in the summer of 1947, Holloman won 18 games and lost 17 for Macon. He began the 1948 season with Macon but was promoted to the Nashville Vols, the Cubs’ Double-A affiliate in the Southern Association. He played there on and off through 1951. His combined record in 1948 was 15-5; in 1949, spent entirely with Nashville, he was 17-10.

It was in “Music City” that Alva Lee became “Bobo.” At the time, 6-feet-2, 220-pound right-hander Bobo Newsom was an American League All-Star pitcher. Larry Gilbert, the Vols’ owner, gave Holloman the same nickname saying, “You’re big, you have a strong arm, you like to pitch and you like to talk. You remind me of Bobo Newsom.”7 Holloman was a boastful, overenthusiastic, harmonica-playing, hot-headed man. Bobo was also superstitious: each time he entered a game, he would stop near the foul line on his way to the mound, bend down and draw the initials “GN” in the dirt — letters that stood for his son Gary and wife Nan. He considered using “NG” — but that, he said, did not connote a positive outcome.

In 1950 Bobo pitched over 200 innings for the fourth time in the first five years of his professional career. He picked up 13 wins against 13 losses while pitching for both Nashville and Shreveport, Louisiana, a Texas League team. In 1951, after a poor start at Nashville, Holloman and the Cubs parted ways. They sold his contract to Albany of the Eastern League, which in turn sold him on to Augusta, an unaffiliated club in the South Atlantic League. With an 11-9 record, he pitched well enough to be noticed by fellow Athens, Georgia, resident Spud Chandler. The former New York Yankee pitcher, then a scout, influenced Augusta to sell Bobo’s contract to the Syracuse Chiefs (also unaffiliated) of the International League in 1952. At age 29, he was at last just a step away from the majors.

During the ’52 season Holloman had an appendectomy and lost about one month of playing time. Yet he put together a rather impressive 16-7 record and 2.51 ERA in 183 innings pitched, with 12 complete games including a one-hitter. He allowed 123 hits, the fewest of any pitcher in the International League that year — and only six of them were extra-base hits.8

Bobo Holloman loved to throw. In the days before pitch counts and relief specialists, he averaged more than 210 innings per year over the first seven seasons of his pro career (1946-1952), not counting winter ball or spring training.

The best of those winter seasons came in 1952, right after his success with Syracuse. At the suggestion of his International League opponent, future Brooklyn Dodger Junior Gilliam, Bobo played for the Santurce Cangrejeros club in Puerto Rico. Holloman was both the Crabbers’ ace and workhorse, leading the league with 15 wins.9 In the Puerto Rican league finals against San Juan, he pitched a 13-inning 7-5 victory on two days’ rest, enabling Santurce to reach the Caribbean World Series in Cuba. Despite his heavy workload, he got two of the team’s six wins in the round robin, both over the Caracas Leones.10 The Crabbers were undefeated.

Coupling his regular-season and postseason output for Santurce with his Syracuse victories, he probably had more wins that year than any other professional pitcher. On the strength of that outstanding performance, Big Bobo was finally headed to the big leagues. In October 1952 he had been traded by Syracuse to the St. Louis Browns for pitcher Duke Markell and $35,000 ($10,000 up front and $25,000 if Holloman remained on the Brownies roster past June 15). The Browns had resided in or near the basement of the American League since 1946, and Bobo was hoping to make a difference.

Bobo Holloman made his major-league debut on April 18, 1953, in relief. He thought he was best as a starter, but manager Marty Marion used Holloman only out of the bullpen. And even at that, Bobo was not very effective in April. In four brief outings, he pitched 5 1/3 innings, allowing five runs on 10 hits and three walks. His ERA was nearly 9.00.

Nevertheless, Holloman nagged his manager on several occasions begging for a chance to start. A few times in early May when Marion thought he might start Bobo, the game got rained out. But finally “Slats” yielded to Holloman’s constant pleas and started him against the Philadelphia Athletics in a night game on May 6 at old Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis. Team owner Bill Veeck explained why he agreed with Marion to start Holloman. He said the Athletics were the “softest competition we could find” and if the Browns didn’t give Bobo his chance, “he’ll be on our ears all the way to the train station.”11

May 6, 1953, was a rainy night. Only 2,473 fans were in attendance — including Gary and Nan — when Holloman took the mound for the home team. Veeck gives one of the best accounts of what happened next in his autobiography Veeck — As In Wreck:

[E]verything he threw up was belted. And everywhere the ball went, there was a Brownie there to catch it. It was such a hot and humid and heavy night that long fly balls which seemed to be heading out of the park would die and be caught against the fence. Just when Bobo looked as if he was tiring, a shower would sweep across the field, delaying the game long enough for him to get a rest. Allie Clark hit one into the left-field stands that curved foul at the last second. A bunt just rolled foul on the last spin. Our fielding was superb. The game went into the final innings and nobody had got a base hit off Big Bobo. On the final out of the eighth inning, Billy Hunter made an impossible diving stop on a ground ball behind second base and an even more impossible throw. With two out in the ninth, a ground ball was rifled down the first base line — right at our first baseman, Vic Wertz. Big Bobo had pitched the quaintest no-hitter in the history of the game.12

The Browns won, 6-0. Holloman struck out three, but six batters reached base — one on an error (Holloman’s own) and five on walks. Three of those walks were in the ninth inning. And to top off this amazing night, Bobo’s improbable pitching performance was matched only by his improbable batting performance. He collected three RBIs that night with two singles — his only hits and RBIs in his major-league career.

Bobo Holloman never pitched another complete game. He came close on June 21 when he defeated the Red Sox on two hits, 2-0 — his third and last major-league victory — but he needed relief help from Satchel Paige in the ninth inning. Plagued with a sore arm, Bobo pitched in his final major-league game on July 19, 1953. His pitching line for that season — and for his career — is 22 appearances, 10 starts, 65 1/3 innings, 3 wins, 7 losses, 25 strikeouts, 50 walks, 5.23 ERA…with one complete-game shutout.

On July 23, 1953, the Toronto Maple Leafs, a Triple-A team in the International League, purchased Holloman’s contract from Bill Veeck. Holloman appeared in 13 games, starting eight of them, but he clearly was not regaining his form. He allowed 53 hits and 31 earned runs and walked 43 batters in 55 innings. Bobo returned to Puerto Rico for the Winter League, but left early with an 0-2 record and a sore arm.13 The following summer he bounced around playing for five different teams in five different minor leagues. But by the end of 1954 Holloman was out of baseball entirely at age 31.

He returned to Georgia and made a living driving trucks for a while, as he had done during his playing days. He then worked as a foreman at Roper Hydraulics, a tool and die company in Commerce, Georgia. The local hero stayed involved in athletics in a small way by coaching Little League baseball and officiating high school football, but he kept his competitive juices flowing in a big way by taking up golf. He soon became a par golfer, and along the way, he imparted the love of the game to his son, Gary. At about age 14, the Little Papoose caddied for the Big Chief until Gary himself became quite good in his own right. Following his collegiate golfing career at the University of Georgia, Gary got his Professional Golf Association card in 1974. Over the years, father and son entered and won several tournaments in Georgia.

But Bobo was a disappointed and resentful man when his powerful right arm betrayed him and forced him out of baseball. Always combative on the field, now his battle was with alcoholism. Yet, just as he fought through the ninth inning in his miracle game on that rainy night in St. Louis, he fought off his sickness in 1972. On the 30th anniversary of his marriage to Nan, Bobo swore off drinking forever.14

He turned his energy to starting his own advertising company which he called BoNanGa, named, of course, after Bobo, Nan, and Gary. In 1974, he also worked as a part-time scout for the Baltimore Orioles in the Georgia area. He was invited back to participate in several Old-Timers games in major league parks. On May 1, 1987, Alva Lee “Bobo” Holloman Jr. died of a sudden heart attack at his home in Athens, Georgia. He was 64.

In February 2006, Bobo was inducted into the Thomaston-Upson Sports Hall of Fame. His adoring widow, Nan, accepted the plaque.

Nan Holloman died on March 19, 2023. She was 99 years old. She was survived by their son, Gary, and two grandchildren, Shane William Holloman and Christopher Travis Holloman.

Last revised: May 8, 2023 (zp)

Author’s note

I cannot write this biography without acknowledging the truly spiritual joy I experienced by meeting Bobo’s widow Nan Holloman. Nan spoke with me by phone from her home in Athens, Georgia, on May 23, 2005. To help my research, she sent me one of her last remaining autographed copies of This One and That One: The True Life Story of BoBo “No-hit” Holloman, the book she wrote in 1975 (printed by Southeastern Color Lithographers, Athens, Georgia). Thank you, Nan.

However, with apologies to Nan, in this biography I spell Alva Lee’s nickname as “Bobo.” Although in her book and in her letters to me, Nan spelled her husband’s nickname as “BoBo,” in all other published accounts that I found, his nickname was spelled as “Bobo.”

Sources

In addition to the sources in the notes, the author relied on Holloman’s player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, as well as to several baseball-related websites and, accessed online, from the New York Times, Chicago Daily Tribune, and Baseball Digest. Other resources not already cited in the endnotes include:

Various Authors. The Ol’ Ball Game: A Collection of Baseball Characters and Moments Worth Remembering (New York: Barnes and Noble, 1990).

Graham, Frank. Great No-Hit Games of the Major Leagues (New York: Random House, 1968).

Notes

1 The second-fewest wins by a major-league pitcher who threw a no-hitter: 7, by George Davis.

2 The list of rookies includes pitchers who pitched their no-hitters in a year after their debut year — in the case of Sam “Toothpick” Jones, four years after his MLB debut! — in accordance with MLB rules.

3 Wilson Alvarez on August 11, 1991, and Clay Buchholz on September 1, 2007, threw their no-hitters in their second major league start; Charlie Robertson threw his on April 30, 1922, which was his third start; and two others threw their no-hitters in their fourth major-league start — Bo Belinsky on May 5, 1962, and Burt Hooton on April 16, 1972 (the first start of his first full major league season).

4 Published accounts of Holloman’s date of birth vary from 1923 through 1926. For the March 7, 1923, date of birth used in this biography, the author relies on: (1) This One and That One (1975, Self-published: Third Print 2006) by Nan Holloman, at page 3; (2) the presentation at Holloman’s induction into the Thomaston-Upson Sports Hall of Fame (see http://www.tusportshalloffame.com/ALVA%20LEE%20HOLLOMAN.htm); and (3) the online player profiles published at www.baseball-almanac.com, www.baseball-reference.com, and www.retrosheet.org.

5 Nan Holloman. This One and That One (1975, Third Print 2006), 5.

6 Jorge S. Figueredo. Béisbol Cubano: a un Paso de Las Grandes Ligas, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1995), 251-252.

7 Lowell Reidenbaugh. “Holloman, Facing Axe, Hurls No-Hitter,” The Sporting News, May 13, 1953. See also Nan Holloman, 23. However, some accounts say it was Holloman who named himself “Bobo.”

8 Holloman, 40.

9 Jose A. Crescioni Benítez. El Béisbol Profesional Boricua (San Juan, Puerto Rico: Aurora Comunicación Integral, Inc., 1997), 86.

10 Thomas Van Hyning. The Santurce Crabbers (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1999), 41-42.

11 Bill Veeck, with Ed Linn. Veeck — As In Wreck (Chicago: University of Chicago Press ed., 2001), 297.

12 Ibid., loc. cit. Veeck’s memory was a bit faulty, as it was elsewhere in his memoir. It was Vic Wertz who recorded the last out, but he was the right fielder for the Browns that night, not the first baseman.

13 Thomas Van Hyning. Puerto Rico’s Winter League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1995), 55.

14 Holloman, 85.

Full Name

Alva Lee Holloman

Born

March 7, 1923 at Thomaston, GA (USA)

Died

May 1, 1987 at Athens, GA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.