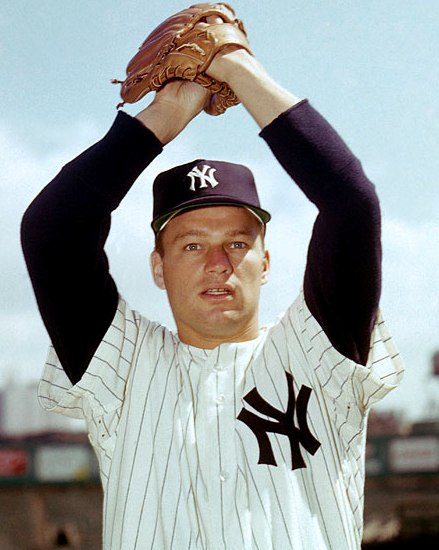

Jim Bouton

Although he became a star for the most famous team in baseball, for whom he helped win three pennants and a World Series, Jim Bouton’s most lasting contribution to the sport would come a few years later, after he lost his fastball and returned to the major leagues as a struggling knuckleballer for an expansion team in Seattle. Bouton’s diary about his 1969 season, Ball Four, became one of the best selling and most beloved of baseball books, making its author either a humorous outsider or a social leper, depending on your point of view. What is not in dispute is that Bouton caused fans to look at the game in an entirely new way, and revolutionized baseball journalism and literature.

Although he became a star for the most famous team in baseball, for whom he helped win three pennants and a World Series, Jim Bouton’s most lasting contribution to the sport would come a few years later, after he lost his fastball and returned to the major leagues as a struggling knuckleballer for an expansion team in Seattle. Bouton’s diary about his 1969 season, Ball Four, became one of the best selling and most beloved of baseball books, making its author either a humorous outsider or a social leper, depending on your point of view. What is not in dispute is that Bouton caused fans to look at the game in an entirely new way, and revolutionized baseball journalism and literature.

While Bouton did not like the way the baseball business was run, he loved the game itself so much that he gave up a high-paying television career to return to the minors several years after his career had ended, and was still playing competitively when he was in his late 50s. A few years later his campaign to save a beloved old minor-league ballpark led him to help form the Vintage Base Ball Federation, bringing 19th century baseball rules, uniforms, and atmosphere to cities and town across the country. Bouton’s detractors had called him a communist during his playing career, but in many ways he was actually a traditionalist, a man who fought on the side of baseball for five decades.

James Alan Bouton was born on March 8, 1939, in Newark, New Jersey. His father, George Hempstead Bouton, of French and English heritage, was attending night school at Columbia when Jim was born but later became a business executive. His mother, Trudy Vischer Bouton, was German and Dutch. Jim was the first of three sons, followed by Bob and Pete, and spent the first 15 years of his life in suburban New Jersey, in Rochelle Park and Ridgewood. He recalled spending much of his spare time trying to make money—delivering newspapers, collecting pop bottles and old newspapers, mowing lawns, and washing cars.[fn]Jim Bouton and Leonard Shecter (editor), I’m Glad You Didn’t Take It Personally (William Morrow, 1971), 177-178.[/fn] The Bouton boys were New York Giants baseball fans and often went to the Polo Grounds to watch the team, seek out autographs, and try to retrieve baseballs during batting practice.

Bouton was not a big kid and not particularly athletic, but he possessed an extraordinary desire that would stick with him through his later baseball career. Sports did not come easily, but he worked harder than other people and found that he could compete. The challenge became greater when his father’s job took the family to Chicago Heights, Illinois, about 30 miles south of Chicago. His new high school, Bloom Township, was much larger, and he found he could make neither the football nor basketball team, and barely made the baseball team. In his sophomore year he was known as “Warmup” Bouton, because the coach would let him only warm up until the final game. He later had success both for the high-school team (pitching a no-hitter his senior season) and in American Legion ball. He threw a variety of pitches, including a knuckleball, but did not throw particularly hard.[fn]Bouton and Shecter, I’m Glad You Didn’t Take It Personally, 179-186.[/fn]

He enrolled at Western Michigan University with the assurance that a good season for the freshman baseball team would earn him a scholarship for his sophomore year. He pitched well and got the scholarship, and then played in a Chicago amateur league during the summer of 1958. He pitched two great games in the league tournament, and suddenly professional scouts were coming around and asking him to work out. George Bouton wrote a letter to all 16 major-league teams telling them that his son was planning to sign a contract by Thanksgiving, advising them to get their bids in. The New York Yankees’ Art Stewart offered $30,000, and the Boutons signed in late summer.[fn]Jim Bouton, with Leonard Shecter (editor), Ball Four: My Life and Hard Times Throwing the Knuckleball in the Big Leagues (World, 1970), 40-42.[/fn]

The 20-year-old Bouton split the 1959 season between two Class D clubs, the Auburn (New York) Yankees in the New York-Pennsylvania League, and Kearney (Nebraska) in the Nebraska State League. He did not pitch particularly well, a combined 3-8 with a 5.52 ERA in 22 games, but showed enough promise to get promoted to Greensboro, in the Class B Carolina League, for 1960. There, he finished 14-8 with a league-leading 2.74 ERA that season, and followed in 1961 with a 13-7 record and a 2.97 ERA for Amarillo in the Double-A Texas League. Both teams won their league’s pennants easily, and Bouton was one of the principal reasons.

Bouton went to spring training with the Yankees in 1962 with little expectation that he would make the team, but a string of good outings earned him a spot as the last man on the staff. Bouton had been given number 56 in spring training, a number indicative of someone not likely to make the team, but he wore this number for the rest of his career, as a reminder of how hard he’d had to work to make it. The Yankees that Bouton joined were a legendary bunch, led by Mickey Mantle, Whitey Ford, Yogi Berra, and Roger Maris, fresh off setting the single-season home run record the previous year.

Bouton pitched only once in April 1962, and got his first start in the Yankees 21st game, on May 6 against the Washington Senators at Yankee Stadium. On that day he allowed seven hits and seven walks, but held on for a complete-game 8-0 shutout. For the season, the 23-year-old Bouton pitched 36 times, including 16 starts, and finished 7-7 with a 3.99 ERA. The Yankees beat the Giants in the World Series, though Bouton did not pitch.

After serving a six-month hitch in the Army, Bouton broke through spectacularly in 1963, finishing 21-7 with a 2.53 ERA despite not joining the starting rotation until May 12. He ended up with 30 starts and 10 relief appearances. Bouton also pitched an inning in the All-Star Game, retiring Ken Boyer, Dick Groat, and Julian Javier in order. On September 13 his shutout over the Twins clinched the Yankees’ fourth straight pennant. He started the third game of the World Series in Los Angeles, but lost 1-0 to Don Drysdale, and the Yankees fell to the Dodgers in a four-game sweep.

Bouton had thrown a number of pitches in the minor leagues, including the knuckleball, but it was a conversation with Johnny Sain in 1961 that turned him into more of a traditional fastball-curveball pitcher. Bouton was a tremendous competitor throughout his career, famous for throwing so hard he often lost his cap after releasing the pitch. Asked about his competitiveness in 1965, he allowed, “I would smash into a second-baseman to break up a double play, or do anything I possibly could to win.”[fn]Max Nichols, “Harmon Killebrew and Jim Bouton: A Ballplayer’s Image,” Sport, July 1965, 31.[/fn] The sportswriter Maury Allen gave Bouton his enduring nickname of Bulldog.

By 1964 the Yankees had dominated baseball for 40 years, with a seemingly unending supply of new talent flowing into the system. Bouton was part of the latest wave of promising youngsters that included Joe Pepitone, Tom Tresh, Phil Linz, and Al Downing, portending many more World Series checks for Bouton. In the meantime, his life was progressing off the field. At Western Michigan he had met Bobbie Heister, whom he married in 1962. Their son Michael was born right after the 1963 World Series, and the family settled in suburban New Jersey not far from where Jim had lived as a boy. By the end of the decade they added Laurie and Kyong Jo, a boy they adopted from Korea who later took the name David.

Even before his stardom, Bouton drew quite a bit of attention in the baseball press. Partly this came about because Bouton liked to have fun, play practical jokes, and imitate characters like Crazy Guggenheim. Before his 1963 World Series start he got on the team bus with a phony newspaper he had had printed up, with a headline that blared, “Bouton Pitches Perfect Game; Fans 18 to Beat LA.” But what drew some of the reporters to him was something else—there was the sense that Bouton put baseball in perspective, and that there was more to him than just the day’s ballgame. After he lost the World Series game, he was emotional, but also recalled losing a big game in high school. “That game was as big to me then as the World Series. I cried after that one.”[fn]Leonard Shecter, “Jim Bouton—Everything in its Place”, Sport, March 1964, 71-73.[/fn]

There was a growing divide in the New York press at this time, between the old-school writers who believed their job was to present the players as heroes, and the new wave of journalists who were looking for a story, or some deeper understanding of what the players were thinking on and off the field. The Yankees players and management were used to being treated as royalty by the likes of Jimmy Cannon, and resented the young writers, whom Cannon derisively referred to as “chipmunks.” When Bouton joined the team he was warned to stay away from the press, but he soon found that he had a lot in common with the newer writers, men like Stan Isaacs, Vic Ziegel, and Steve Jacobson. For their part, the writers discovered that Bouton liked to paint, and to make jewelry, and to talk about more than just the day’s game. When asked his opinions about the Vietnam War, or about civil rights, Bouton would answer directly and honestly. Bouton was good copy, though becoming less popular with his teammates and management.

“After two or three years of playing with guys like Mantle and Maris,” Bouton later wrote, “I was no longer awed. I started to look at those guys as people and I didn’t like what I saw. They were fine as baseball heroes. As men they were not quite so successful. At the same time I guess I started to rub a lot of people the wrong way. Instead of being a funny rookie, I was a veteran wise guy. I reached the point where I would argue to support my opinion and that didn’t go down too well either.”[fn]Bouton and Shecter, I’m Glad You Didn’t Take It Personally, 190.[/fn]

Before the 1964 season, Leonard Shecter, a writer for the New York Post and a friend of Bouton’s, wrote a glowing profile in Sport magazine. In summarizing Bouton’s hobbies and goofy personality, Shecter wrote, “All this is enough to have earned Bouton a reputation as a bit of an oddball. Of course he is not. He stands out because he is a decent young man in a game which does not recognize decency as valuable.” One can imagine what his teammates must have thought while reading the story. Shecter described Bouton as someone who, if things didn’t work out, would find another way to “make the world a better place.” But Bouton left no doubt where his heart lay. “Baseball is what I wanted,” he said.[fn]Shecter, “Jim Bouton—Everything in its Place.”[/fn]

Bouton also battled with the Yankees over his contract every year and, even worse, told the press the details of what he was asking for and what the Yankees were offering. Ralph Houk, who became the Yankees’ general manager after the 1963 season, asked Bouton why he was telling the writers what he was making. “If I don’t tell them, Ralph,” Bouton said, “maybe they’ll think I’m asking for ridiculous figures. I just want to let them know I’m being reasonable.”[fn]Bouton and Shecter, Ball Four, 7.[/fn] This angered Houk, but Bouton was proved right. When the writers discovered that the Yankees forced Bouton to accept just $18,500 for the 1964 season, most of them took the pitcher’s side.

In 1964 Bouton had another excellent year, finishing 18-13 with a 3.02 ERA, while leading the league with 37 starts. He started and won two World Series games, a 2-1 Game Three victory decided by a Mickey Mantle home run in the bottom of the ninth, and an 8-3 victory in Game Six. Over three World Series starts in his career, Bouton now had a 2-1 record with a 1.48 ERA. Despite Bouton’s victories, the Yankees lost to the St. Louis Cardinals four games to three, and the season would prove to be the end of the Yankees’ run of pennants, and the stardom of James Alan Bouton.

The pitcher showed up in 1965 with a sore bicep, but he and the Yankees decided he would just pitch through it. As it happened, his arm never really recovered. For the season he finished a dreadful 4-15 with a 4.82 ERA, while his team dropped all the way to sixth place, their first losing season since 1925. The next season was considerably better for Bouton, as his ERA dropped to 2.69, the best on the team among 100-inning pitchers, but the Yankees’ inept offense was the primary cause of Bouton’s 3-8 record and the team’s last-place finish. Now 27 years old and just two years removed from World Series stardom, his place was suddenly no longer secure on the major-league team.

Bouton made the Yankees in 1967 but a string of poor outings got him demoted to Syracuse, the Yankees’ Triple-A affiliate, in late May. He put up a 3.36 ERA in the minors, which earned him a 2-8 record in 15 starts. The demotion did help launch Bouton’s writing career, as he published an article for Sport on his life in the minor leagues. He spoke mainly of the difficult working conditions, but concluded, “The roughest part is having to admit I’m not good enough, and this is the biggest reason why I’ll be fighting to make it back to the big leagues.”[fn]Jim Bouton, “Returning to the Minors, Sport, April 1968, 30.[/fn] Bouton returned to the Yankees in August and pitched better, reducing his season ERA from 6.27 (at the time of his demotion) to 4.67 for the season.

He made the Yankees again in 1968, but after he posted a respectable 3.68 ERA in just 12 games, his contract was sold to the Seattle Pilots, a team that would not begin play until 1969. In the meantime he played the remainder of the 1968 season with the Triple-A Seattle Angels. Though he started poorly, late in the season he made the fateful decision to rely almost exclusively on his knuckleball and ran off a series of good starts. As the year ended he had hopes that he could make the Pilots’ staff the following spring.

Making Bouton’s job a bit tougher was his continued willingness to speak up when he felt there was a worthy cause at stake. In early 1968 he signed a statement supporting an American boycott of the coming Mexico City Olympic Games if South Africa’s whites-only teams were allowed to participate in international competitions. The country had been barred by the Olympics beginning in 1964, but still took part in other events around the world. Bouton went to Mexico City to try to meet with representatives of the US Olympic Committee about the issue, but was rebuffed. He wrote about the cause and his ordeal in an article for Sport the next winter.[fn]Jim Bouton, “A Mission in Mexico City,” Sport, August 1969.[/fn]

In the meantime he had begun taking notes on what was to become his historic book. In 1969 he spent most of the season with the new Seattle Pilots, with a brief demotion to Vancouver and a late-season trade to the Houston Astros. Overall he pitched in 80 games, almost all of them in relief, and finished the season in a National League pennant race. It was easily his best season since 1964, and at 30 years old he had reason for optimism that he had resurrected his career, albeit in a lesser nonstarring role for the Houston Astros.

In the meantime he had begun taking notes on what was to become his historic book. In 1969 he spent most of the season with the new Seattle Pilots, with a brief demotion to Vancouver and a late-season trade to the Houston Astros. Overall he pitched in 80 games, almost all of them in relief, and finished the season in a National League pennant race. It was easily his best season since 1964, and at 30 years old he had reason for optimism that he had resurrected his career, albeit in a lesser nonstarring role for the Houston Astros.

More importantly for his place in history, Bouton took notes and spoke into a tape recorder almost every day all season and sent the tapes to Shecter, who worked with him to turn the material into a book. After a few rejections, World published Ball Four—My Life and Hard Times Throwing the Knuckleball in the Big Leagues, in the spring of 1970.

Other than a few roommates, few people knew that Bouton was working on a book. The first excerpts were published by Look magazine in May 1970 and caused a firestorm within the game. Former and current teammates, other players and baseball writers around the major leagues, and baseball management were outraged at Bouton’s stories of ballplayers’ drug use and sexual hijinks. Bouton was hauled before Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, who publicly admonished the pitcher. Bouton later credited Kuhn for helping book sales.

On the bright side, once the book was released on June 21 it received mainly glowing reviews from the respected book critics and journalists, who looked past the titillating passages to see the struggles and joys Bouton endured while trying to hang on in the big leagues with an expansion team. (For a more detailed look at the book and its response, read the accompanying article.)

Although Bouton began the 1970 season in the Astros’ rotation, he did not pitch well at the start of the season or after. By the time the book came out, his ERA was over 6.00, and the anger over the book likely did not help. In late July Bouton (4-6, 5.40) was demoted to Oklahoma City, where he was bombed in two straight starts. After the second outing, Bouton decided to retire from baseball, beaten down by his poor pitching and the continued fallout from Ball Four. In the coming decades, Bouton retained some friendships with his former teammates, but the baseball establishment, especially the New York Yankees for whom he had starred, continued to shun him.

Bouton’s first post-baseball career was on television, working as a sportscaster in New York City. His penchant for doing things his own way continued in his new profession, as he focused less on the high-profile professional teams and more on girls high-school basketball teams or weightlifting clubs. His reportage also led him to participate in roller derby matches and rodeo events, to bring his audience closer to the action. Bouton’s broadcasts were popular with the public, though the local professional teams were unhappy that he had no interest in simply promoting their businesses as television had been doing for years. In 1971 he put out a second book, I’m Glad You Didn’t Take It Personally, about the reaction to Ball Four, his retirement from the game, and his early days as a sports reporter.

In 1973 Bouton landed a part in his one and only movie, playing the bad guy Terry Lennox in Robert Altman’s cult classic The Long Goodbye, which also starred Elliott Gould. In 1976 CBS aired five episodes of a television version of Ball Four. Bouton was one of the creators and primary writers for the show and played the main character. The critics blasted the show and the audience stayed away, leading to its quick cancellation.

Meanwhile Bouton continued to play baseball in various adult leagues in suburban New Jersey, still loving the competition and the game. In 1975 he spent a few weeks with the Single-A Portland (Oregon) Mavericks (Northwest League), pitching five games and putting up a 4-1 record and a 2.20 ERA. Two years later he decided to put his lucrative television career on hold and get back to baseball full time. He began the year with Knoxville, the White Sox’ Double-A affiliate in the Southern League, for whom he went 0-6 before drawing his release. From there he traveled to Durango to pitch in the Mexican League, where he finished 2-5. Finally he landed back with the Portland Mavericks, and again found success, with a 5-1 record. Still, it was the lowest level in the minor leagues and Bouton was now 38 years old.

He persevered. He met Ted Turner, the young maverick owner of the Atlanta Braves, who promised him another shot. After Bouton pitched well in the spring, and then beat the Braves in an exhibition game in May, Turner gave him a job with Atlanta’s Southern League affiliate in Savannah, where he found his knuckleball again. In 21 games, all starts, Bouton finished 11-9 with a 2.82 ERA, and Savannah won the league title. Miraculously he was called up to the Braves in September, more than eight years after his retirement.

The 1978 Braves were a bad team going nowhere, but Bouton was facing big-league hitters again, including the Dodgers, Giants, and Reds, who were fighting for the division title. He started five games, and pitched well in three of them. He beat the Giants 4-1 on September 14, his first major-league victory in eight years. After a 2-1 loss to the Reds, their manager Sparky Anderson allowed, “We didn’t even hit the ball hard off of him, and got two runs we shouldn’t have gotten.”[fn]Jim Bouton, Ball Four Plus Ball Five, 1981.[/fn] Bouton finished 1-3 with a 4.91 ERA in his three weeks back at the top. After the season he retired again, saying that he had achieved his goal and had nothing left to prove to himself.

Bouton’s life off the field was changing dramatically as well. His marriage with Bobbie, whom readers had come to know so well in his books, became rocky after his first retirement and ended in the late 1970s. Their three children remained close with both parents. He soon met and married Paula Kurman, an academic and writer, and the two blended their families (Paula had two teenage children of her own) and their professional lives.

Bouton remained in the public eye, speaking on college campuses all over the country about his big-league career and famous book. He and Rob Nelson, a teammate in the late 1970s with the Portland Mavericks, developed a product called Big League Chew, shredded bubble gum designed to look like chewing tobacco, a popular vice among ballplayers. They sold the idea to Wrigley, and 30 years later the gum was still selling well. Bouton invented and sold a few other ideas, including personalized baseball cards for fans.

He continued to write occasional stories for newspapers and magazines, and updated his best-selling book in 1981, 1990, and again in 2000. In 1994 he teamed up with Eliot Asinof on Strike Zone, a novel about baseball that received positive reviews.

Bouton suffered a tragedy in 1997 when his beloved daughter Laurie was killed in an automobile accident. The devastated Bouton retreated into depression, an ordeal he describes fully in an epilogue to the 2000 edition of Ball Four.[fn]Jim Bouton, with Leonard Shecter (editor), Ball Four: My Life and Hard Times Throwing the Knuckleball in the Big Leagues, revised (Bulldog Publishing, 2000).[/fn] A year later his oldest son, Michael, wrote an op-ed in the New York Times, telling of his father’s suffering and asking that the Yankees forgive Bouton for his book, and invite him the next month to Old Timers Day, an annual event that had long shunned him. The Yankees did invite Bouton, leading to an emotional reunion with his fans, his old ballpark, and many of his teammates. He faced just one batter, but to the delight of the crowd got his cap to fall off on his first pitch.

In 2003 Bouton got involved in a fight to save baseball in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, a town whose beloved Wahconah Park, an old WPA-era ballpark, had been deemed inadequate by baseball’s minor leagues. The politicians in Pittsfield backed the construction of a taxpayer-funded stadium, built on (Bouton helped discover) polluted land owned by General Electric, who were eager to sell the land to the city. Bouton’s campaign helped saved Wahconah and defeat the proposed ballpark, but the city did lose minor-league baseball until 2010, when a team from the independent Canadian-American League moved into Wahconah. Bouton told the frustrating tale of his ordeal in the 2003 book Foul Ball (Bulldog Publishing), which he substantially updated in 2005 (Lyons Press).

Bouton never fades too far from the public eye. Anytime there is an anniversary for Ball Four, or some organization comes out with a list of great sports books (Ball Four always near the top), Bouton is called on to speak about it again, and he tells many of the same stories. Among many honors, his book was named one of the Books of the Century by the New York Public Library, the only sports book on their list. The critics have largely melted away, and the baseball writers of today not only read his book as a child, but might have become journalists because of his book. The unfair labor conditions Bouton wrote about are relics of the past, and he played no small role in turning the public in favor of the players in the 1970s.

In 2010 Bouton and his wife, Paula, were still living in their home in the Berkshires, where Bouton kept occupied by building stone walls. In September 2010 he attended a 40th-anniversary celebration of his classic book in Burbank, California, leading to another round of national media interviews. Among other things, the world learned that Bouton was working on writing a theatrical musical version of Ball Four. The famous last sentence of Bouton’s book (“You spend a good piece of your life gripping a baseball and in the end it turns out that it was the other way around all the time”) relates to how an aging journeyman pitcher loved the game and could not give it up. Forty years on, baseball fans showed no signs of setting aside their appreciation for his master work.

Postscript

Bouton died at the age of 80 on July 10, 2019, at home with his wife, Paula Kurman, after battling a brain disease linked to dementia for several years.

Full Name

James Alan Bouton

Born

March 8, 1939 at Newark, NJ (USA)

Died

July 10, 2019 at Great Barrington, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.