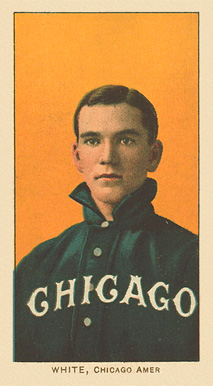

Doc White

The Los Angeles Dodgers clubhouse was filled with press and well-wishers the evening of June 3, 1968, all there to celebrate the fifth consecutive shutout of veteran right handed pitcher Don Drysdale. Amid the throng came longtime clubhouse man Nobe Kawano, holding a telegram for Drysdale that had just come in from Silver Spring, Md. Drysdale asked him to read the telegram, which contained the following sentiment:

The Los Angeles Dodgers clubhouse was filled with press and well-wishers the evening of June 3, 1968, all there to celebrate the fifth consecutive shutout of veteran right handed pitcher Don Drysdale. Amid the throng came longtime clubhouse man Nobe Kawano, holding a telegram for Drysdale that had just come in from Silver Spring, Md. Drysdale asked him to read the telegram, which contained the following sentiment:

“CONGRATULATIONS ON WINNING YOUR FIFTH STRAIGHT SHUTOUT AND EQUALLING MY RECORD. I WILL BE ROOTING FOR YOU TO BREAK IT. IT WILL BE A GREAT SATISFACTION TO ME TO HAVE SOMEONE WHO IS A CREDIT TO THE GAME BREAK MY RECORD.”

The telegram was signed G. Harris “Doc” White — and came from a man who had pitched five straight shutouts himself 64 years earlier. White’s record remains his greatest legacy, yet was only part of the remarkable career of a true baseball renaissance man whose talents extended far beyond the diamond.

Guy Harris White was born the seventh son of a seventh son on April 9, 1879 in Washington, D.C. His father, George White, was a powerful business force in the nation’s capital and owned its only iron foundry at the time. One of his George’s sons, Charles Stanley White, became one of Washington’s most prominent physicians, and his youngest child was also urged to go into the medical profession. Along the way, Guy White developed a secondary interest in playing baseball, at which he excelled at Washington’s Central High. During his high school years, White also met his future wife, Iva Martin, with whom he enjoyed a marriage of over 50 years.

With his studies still coming first, White enrolled at Georgetown University in 1897. He joined the baseball team in the spring of 1898 and quickly became its star pitcher and outfielder. The highlight of his college career came against Holy Cross in 1899 in which White struck out the first nine batters, earning him the attention of professional scouts. White stuck to the books, however, working hard toward a degree in dentistry until the end of his junior year in 1900. That summer, he joined the Fleischmann’s Mountain Athletic Club, a semi-pro team that also featured future major leaguers Red Dooin and George Rohe. White’s continued pitching success was witnessed by star Philadelphia outfielder Roy Thomas, who urged his owner John Rogers to sign him.

Rogers signed White to a contract for $1,200, with a promise of a $200 bonus if he had a good season. Without a day of minor league experience, the young left hander stepped into the rotation of a strong veteran team boasting three Hall of Famers in its starting lineup. White more than met the challenge all season long, winning his debut with a six hitter against Brooklyn and 15 games in total that season. Always a good hitting pitcher, White batted .276 and helped his team to a 15-1 victory on June 24 with four hits including a inside the park home run. In 1902, the Phillies slumped badly and White’s 16-20 record reflected it. However, he finished second in the National League with 185 strikeouts, including four in one inning against Brooklyn on July 21 (the first time this had been accomplished since the advent of the 60′ 6″ pitching distance in 1893). Rogers was only too happy to pay his budding star his bonus money, yet 1902 would be his last season in Philadelphia.

After the 1901 season, White returned to Georgetown to finish his studies. He received his dentistry degree in 1902 and returned to Washington after the season to open a dental practice. However, in the off-season he became the object of a bidding war between Philadelphia and Chicago in the nascent American League. Chicago offered White a raise to jump to the new league, which he quickly accepted. Philadelphia then attempted to keep White by offering him three times what Chicago offered. Before he could jump back, a peace settlement was made between the two leagues, and as part of that it was decided that White should go to Chicago. In his first season, White won 17 games to lead the staff, and his 2.13 ERA ranked fourth in the league. A highlight came on September 6 when he pitched a 10 inning one hitter against Cleveland. The college educated White also earned the respect of some of his rough and tumble teammates by continuing to rank in the league leaders in hit batsmen. After the season, he again returned to his dental practice, which had now earned him the nickname “Doc.”

The White Stockings had struggled in 1903 but contended for the pennant all season long in 1904. Doc White played an important role in the pennant race, winning 16 games with a sterling 1.78 ERA. The 1904 season saw White become a more complete pitcher, with improved control. Although slight of stature, the lefty threw a hard fastball and also relied on a sinker to get him out of trouble. In September, he single-handedly kept the team in contention with a shutout streak that remained a baseball record for the next 64 years.

The streak began on September 12, when White shut out Cleveland 1-0. Four days later, he took a no-hitter into the eighth inning at St. Louis. With one out, Tom Jones hit a triple, ending the no hit and putting another slim 1-0 lead in jeopardy. Jones was thrown out at home trying to score on a grounder, and the win and shutout #2 were preserved. On September 19, he had an easier time with Detroit, shutting them out 3-0 on just two hits.

With the White Stockings trying to hang on in the pennant race, White pitched his fourth straight shutout, defeating the Philadelphia Athletics 4-0 on September 25. On September 30, shutout #5 came at the courtesy of the first place New York Highlanders, again by a 4-0 total. With staff mainstay Frank Owen hurt, White took his turn in the rotation and agreed to start both ends of a doubleheader against New York on October 2. His streak finally came to an end in the first inning of the opener, when Willie Keeler scored from second on a single by Jimmy Williams. White then shut out for the rest of the game to win 7-1. In the nightcap, the exhausted lefty finally gave out, losing 6-3. It had been a magnificent stretch of pitching indeed.

By 1905, White had established himself as one of the game’s elite pitchers. He posted a 17-13 record and his ERA of 1.76 ranked second in the league. Off the field, he was also drawing attention. Loquacious and bright, he proved to be a prime target for newspaper reporters seeking interviews. White’s “Words of Wisdom” columns appeared in the Chicago Tribune, offering his thoughts on a variety of baseball subjects. These ranged from the use of the mud ball (too dangerous), college players (ironically he felt they should go to the minor leagues first), and the inability of left handed batters to hit left handed pitching (not enough practice). He was well respected by ownership, who asked him to help design the team’s uniforms, as well as teammates, who chose him to represent the team at the first formative meetings of the players union in 1912.

After two years of near misses, the White Stockings won the American League pennant to set up a showdown with the cross-town powerhouse Chicago Cubs. White had enjoyed another strong season, winning 18 games and leading the American League with a 1.52 ERA. The White Stockings had been dubbed “the Hitless Wonders” for their anemic attack and were heavy underdogs heading into the World Series. However, they won the first game 2-1 setting up a match up between White and Chicago’s Ed Reulbach.

White had not pitched much at the end of the season due to illness and arm fatigue, and was hit hard in a 7-1 loss, while Reulbach allowed only a singe hit. The teams split the next two games setting up a pivotal Game Five. The game surprisingly turned into a slugfest, with the White Stockings holding an 8-6 lead in the seventh. With one out and a runner on second, manager Fielder Jones called on White to relieve Ed Walsh, who had become noticeably unnerved by his team’s terrible defense that afternoon (the White Stockings finished with six errors). Helped by some nice fielding plays by George Davis, he shut out the Cubs the rest of the way to save the win. The next day, Jones again called on White, this time to start. The left hander again came through, beating the Cubs 8-3 in a complete game to win the series. After the game, White made a victory speech to a huge crowd of fans who had come to see him at the home of manager Jones.

In 1907, White enjoyed the best season of his career. Over the year he walked only 38 batters in 291 innings and posted a 2.26 ERA on the way to the only 20 win season in his career. He tied for the league lead in wins with 27, and achieved another remarkable streak. On September 11, 1907, White chose to give an intentional walk to St. Louis Browns first baseman Tom Jones to get out of a tight spot. White got out of trouble, perhaps without realizing that this was the first batter he had walked in 65⅓ innings, an American League record.

Although overshadowed in 1908 by his teammate Walsh, White won 18 games and helped keep the team in an exciting pennant race that went down to the season’s final day. Chosen to start over a well rested Frank Smith, who had been feuding with manager Jones, White went to the mound against Detroit on October 6 with a chance to give the team a pennant. Working with only a day’s rest, White could not get out of the first inning of a 7-0 loss that cost the team the championship and Jones his job.

Off the field, White had stopped practicing dentistry in the off-season. Active in his church, he showed yet another talent by leading his church choir in song and on the piano. He collaborated with Chicago newspaper columnist Ring Lardner on two songs, providing the music for Lardner’s words. The first, a sensitive ditty entitled “A Little Puff of Smoke, Good Night” became quite popular in 1910 and is still held in high regard by fans of the genre. The second, 1911’s “Gee It’s A Wonderful Game” celebrated his baseball roots. During his later baseball years in California, he extended his church work to a short vaudeville tour in which he mixed spirituals and popular songs

The team and White struggled over the next several seasons. After winning 143 games over his first eight seasons, he slumped to a 46-50 record over the last five years of his career. There were still some high points—in 1909, he battled Walter Johnson twice in 5 days in epic struggles, winning the first 1-0 and pitching the second to a 17 inning complete game 1-1. By 1913, it was clear that his career was coming to an end, as he was only able to pitch in 19 games. After the season he retired as an active major league player, although he did pitch for Venice and Vernon in the Pacific Coast League in 1914-1915.

There are several possible factors to White’s decline. The team behind simply was not as a strong as it had been in his glory seasons. Always slight of stature at 150 lbs or less, White also wore down due to the heavy toll of innings in his best years. The lefty had relied on sinkers, curves, and off speed pitches to get by (by today’s standards he would be considered a “junk ball” pitcher) and American League batters may well have figured him out at last. Ty Cobb would later talk about his success at getting the better of White, who had owned him early in his career. Whatever the reasons, the diminished end of his career does not detract from his strong overall career statistics. White finished his career with 189 wins and a 2.39 ERA. At the time of his retirement, only two left-handed pitchers (Eddie Plank and Jesse Tannehill) had won more games.

After the end of his playing career, White continued to work in baseball. He became interim manager of Vernon during the 1915 season, and worked in a front office job there in 1916 after briefly deciding to manage the Denver Bears. He then became part-owner of the Ft. Worth franchise in the Texas League. After the league suspended play due to World War I, he served as a YMCA director with an aviation unit in Dallas. He ran the Waco franchise in 1919, and then managed Muskegon in the Central League in 1920. After leaving pro ball, his career returned full circle. He returned to his old school, Central High in Washington, as a coach and physical education teacher in 1921. He continued in this post for the next 28 years, while also serving as a pitching coach for the University of Maryland and as a basketball coach at Wilson Teachers College.

White retired from his coaching positions at age 70 in June, 1949. Still, retirement did not prevent him from developing another talent: gardening. White specialized in cultivating roses, and showed his best exhibits in local shows, winning a number of awards and prizes. In 1955, his wife Iva passed away, and he then moved into his daughter’s home in Silver Spring, MD. Despite advancing years and failing health, he still stayed active, answering mail requests for autographs with near-perfect handwriting. White also stayed in close touch with columnist friends Shirley Povich and Bob Addie of the Washington Post. Interviewed on the occasion of his 80th birthday, the old pitcher lamented on the lack of control of modern pitchers. “They can’t pitch four innings without walking somebody—and there’s no excuse for it, they just don’t practice!”

Don Drysdale’s successful run at his record brought Doc White into the limelight for a final time. He had been mostly bedridden in his later years due to the effects of a broken hip in 1957. When reporters attempted to call him for an interview after Drysdale’s streak came to an end, he was too weak to even leave his bed and come to the phone. On February 17, 1969, White passed away just a few weeks short of his 90th birthday, and was buried at Rock Creek Cemetery in Washington, D.C. On and off the field, the musical dentist from Georgetown had made a lasting and memorable contribution to the legacy of the deadball era.

Last revised: October 26, 2022 (zp)

Note

A different version of this biography originally appeared in David Jones, ed., Deadball Stars of the American League (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc., 2006).

Sources

I relied heavily on periodical primary sources drawn from the Doc White files at The Sporting News and Baseball Hall of Fame library. These included a number of newspaper clippings and illustrations from uncited sources, as well as telegrams exchanged between Doc White and Don Drysdale on June 3-4, 1968.

Websites

www.baseball-almanac.com

www.baseballlibrary.com

www.baseball-reference.com (for statistical information)

www.lardnermania.com

Books

Anderson, David W. More Than Merkle. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2000

Porter, David. (ed.) Biographical Dictionary of American Sports: 1992-1995, Supplement for Baseball, Football, Basketball, and Other Sports. Westport: Greenwood Press, 1995.

Periodicals

Chicago Tribune

1904: 9/13, 9/20, 9/26, 10/3

1906: 10/11, 10/14, 10/15

1907: 9/12

1908: 10/6, 10/7

1912: 5/4, 8/31

Washington Post

Obituary, 2/19/69

The Sporting News

Obituary, 3/8/69

Full Name

Guy Harris White

Born

April 9, 1879 at Washington, DC (USA)

Died

February 19, 1969 at Silver Spring, MD (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.