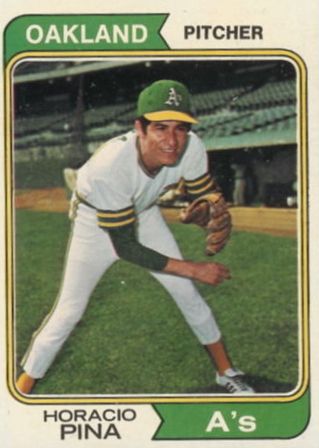

Horacio Piña

This lanky pitcher was the first Mexican player to win a World Series ring. El Ejote – The Stringbean — was a member of the Oakland A’s bullpen in 1973. His motion was quirky and memorable: Whipping the ball from a low side-arm/submarine angle, Piña then swung wide and landed hard with his trailing right foot. NBC’s broadcasts of the 1973 World Series focused on the impact crater that Horacio created.

This lanky pitcher was the first Mexican player to win a World Series ring. El Ejote – The Stringbean — was a member of the Oakland A’s bullpen in 1973. His motion was quirky and memorable: Whipping the ball from a low side-arm/submarine angle, Piña then swung wide and landed hard with his trailing right foot. NBC’s broadcasts of the 1973 World Series focused on the impact crater that Horacio created.

Piña pitched in 314 big-league games from 1968 to 1978, starting just seven times. After 1974 he then went back to Mexico, where he was a very effective starter in both summer and winter ball. His best season was the summer of 1978, highlighted by a perfect game on July 12. His 21-4, 1.94 record earned him a final two-game stint in the majors that September. Horacio then pitched on in Mexico through 1980 until he hurt his shoulder. He entered his homeland’s Baseball Hall of Fame in 1988.

Horacio Piña García was born in Matamoros de La Laguna, in the state of Coahuila. This Matamoros is not the city directly across the Rio Grande from Brownsville, Texas (400 miles east, in the state of Tamaulipas). It is half an hour east of Torreón, the center of Mexico’s ninth-biggest metro area. The Laguna region surrounds Torreón and its twin city Gómez Palacio, just across the Nazas River in the state of Durango.

Horacio’s father was Roberto Piña Trujillo, a corn-mill operator on a communal farm called Ejido las Maravillas. On March 12, 1945, the fourth of Roberto and Nohemí García Castro’s seven children entered the world.1 Before Horacio came José, Óscar, and Silvia; after him were Cuca, Roberto, and Jaime.

Note the tilde (~) in the family name, which the American press left out in his playing days. He never had it on his uniforms in the US either; they read only PINA. Looking back in 2009, though, Piña said it never mattered to him. “I had a lot of discipline. I came in running from the dugout to the field and I left running. What’s more, I didn’t know what that little thing above the ‘n’ was even called! It was only later I found out it’s called a tilde.”

Matamoros is a baseball-loving city, as is much of northern Mexico. Roberto Piña was a semipro pitcher (with a conventional overhand delivery). Horacio, however, barely touched bat and ball growing up — he favored soccer. He played goalie and sweeper because of his height. He only came to baseball by chance at age 17 after picking up a foul ball from a local field called Campo Cámara. His return throw was impressive enough to prompt someone to ask if he wanted to play ball. Horacio demurred, but the additional promise of 50 pesos — good money for the time — got him to join his first team. La Paletería Galindo (a purveyor of paletas, or Mexican popsicles) was the sponsor.2 He later pitched for another team called “Los Chicos del Once.”3

There were other local clubs in Gómez Palacio. During a 1963 game there, the gangling teenager got nicknamed for life. He stood well over 6 feet tall but then weighed little more than 150 pounds.4 A friend named Joaquín Gómez first called him “slice of watermelon” and then Ejote. The latter tag stuck.5

In 1964 Piña played for the “Frankie” team of Gómez Palacio, as well as the Matamoros team in La Liga Mayor de Béisbol de La Laguna. After a regional championship game in the city of Guadalupe Victoria (also in Durango), scouts from the Puebla Pericos organization in the Mexican League approached him.6 One was Nazario Moreno, who played just 32 games at the nation’s top level but remained on the scene in various capacities, including manager. Horacio told them, “I don’t know how to play.” They replied, “We’ll teach you there.” His mother signed the contract, since his father had passed away.7

For the 1965 season, Piña joined Zacatecas in the Mexican Center League (Class A), a Puebla farm club also known as the Pericos (Parrots). He pitched 116 innings in 38 games, winning four and losing six. Control was a problem, as he walked 72 men, fueling a fat 6.60 ERA.

Horacio appeared in just six games with Zacatecas in 1966. He wanted to join the big club in Puebla, then managed by former Cleveland Indians star Beto Ávila (known as “Bobby” in the US). The Pericos reassigned him to the farm team, though, and so Piña went instead to the Monclova Acereros in La Liga del Norte de Coahuila. He also played for Matamoros in La Laguna’s top league again.8

In 1967 Piña made the Puebla team. Even after he threw a 1-0 shutout, the Pericos had their doubts about whether he could be a starter. Horacio therefore decided to return to La Liga del Norte, but Cuban manager Tony Castaño persuaded him to stay.9 Piña went on to win 16 games against 11 losses for the last-place club, while posting a 3.28 ERA. The Mexican Baseball Writers Association did not make its annual MVP and Rookie of the Year selections that year, owing to an internal dispute. The Mexico City sports paper La Aficiónpolled the league’s managers, though, and they named Horacio top rookie.10

Regino “Reggie” Otero, a scout for the Cleveland Indians, was paying attention, Otero, a Cuban who had played briefly with the Chicago Cubs in 1945, had moved into scouting after serving as a coach with the Tribe in 1966. Cleveland worked out a deal with Puebla, and Horacio then joined Reno in the California League (Class A). There he went 1-0, 4.00 in 18 innings across three games.

After the summer season ended, Piña played winter ball at home for the first time in La Liga Mexicana del Pacífico (LMP). The owner of the Culiacán Tomateros, merchant Juan Ley Fong (known as “Chino” for his Chinese birth) brought him aboard. In December 1967 Horacio reeled off an impressive streak of 46⅓ scoreless innings, still (as of 2014) a league record. It started with 13⅔ innings in relief on the 12th; three straight shutouts followed before opponents finally got to him in the sixth inning of his next start. Piña also pitched a no-hitter that winter, winning 2-1.

Horacio pitched in spring training with the Indians in 1968. He opened the season on loan to the Portland Beavers, Cleveland’s Triple-A affiliate, and made five sharp starts, including a one-hitter with nine strikeouts his first time out. Overall, he was 3-1, 0.69 in 39 innings before returning to Puebla in mid-May. That was the deal he made with the Indians front office — under threat of fine and/or suspension — because his salary was lower in Triple-A than the Mexican League.11

El Ejote continued to do well with the Parrots. He went 9-6, although he lost his last four decisions, with a 2.22 ERA. That prompted Cleveland to purchase his contract in mid-August. They were supposed to wait until after the Mexican League season ended on August 16, but manager Alvin Dark wanted his help.12 “There was talk on the team that he was a racist,” said Piña in 2009, “but it wasn’t certain, because there were various Latinos. He gave a chance to everyone, and those who got the job done, we got in.”

Piña made his big-league debut at Cleveland’s Municipal Stadium on August 14. In relief of Luis Tiant, he retired all six Detroit Tigers who faced him, striking out four. Three days later, again at home, he relieved his fellow Mexican Vicente Romo and picked up the last two outs against the Chicago White Sox. It was his first of 38 saves in the majors.

On August 21, Piña made his first big-league start, against the Boston Red Sox at Municipal Stadium. He allowed two runs (one unearned) in 8⅔ innings and left to a standing ovation from the crowd of 8,991. Vicente Romo returned the favor, finishing off the 8-2 victory. One point of interest was that the US papers listed his age as 21 rather than 23.

After the game, Horacio said, “I tired a little in the last inning and I believe this was the hottest night I have ever pitched. It is a little cooler in Mexico where I pitched this year. I was a little nervous at the start and also wild because I couldn’t control my overhand fastball.”13 It is notable that he varied his motion in his earlier years. Also, one of his Latino teammates must have translated, because the rookie spoke little if any English then. Perhaps it was Luis Tiant; in 2009 Piña remembered how good the Cuban was to him. “In any way or whatever thing he would help us. On days off we would get together with the family — a very good person.”

Author Bruce Markusen, who chronicled the Oakland dynasty of the early ’70s, described Piña. “At six feet, two inches, and 160 pounds, the reed-thin right-hander earned the nickname ‘Ichabod Crane’ during his early major league days. An impressive physical specimen he was not.”14 During the ’70s, Horacio filled out to nearly 180 pounds. His wiry hair also grew quite bushy at times (as depicted on his Mexican Hall of Fame plaque and his bust at Campo Cámara).

Piña made the Indians staff in spring training 1969 and pitched in 31 games for them over the first four months, although he spent a brief spell with Portland in April. On the surface, his ERA was an unimpressive 5.21, but a couple of bad outings inflated that number. At the end of July, after the White Sox hit him hard, Cleveland sent Horacio down to Double-A Waterbury.15 He did not appear in a single game there, though — rather, he went home. “I pitched more effectively than others, but I was demoted while they stayed,” he said in 1990. “They (Cleveland) threatened to suspend me.”16 In fact, The Sporting News said he was suspended after refusing to report. 17

On December 5 the Indians traded Piña along with pitcher Ron Law and infielder Dave Nelson to the Washington Senators. In return, they received Dennis Higgins and Barry Moore. The relatively minor deal received little attention at the time, as it was a busy day at the winter meetings and there was other news from the business side of the game: the move of the Seattle Pilots and a power struggle within the league offices.

That winter Culiacán won the first of two LMP titles during Horacio’s time there (unfortunately, Mexico was not part of the Caribbean Series revival in 1970). He ranked these alongside his World Series as the best things that ever happened to him in baseball. About being a Tomatero, Piña said in 2007, “They were 12 unforgettable seasons. I don’t forget that after each season in the big leagues, I arrived in my beloved Culiacán to defend the house of the Tomateros. We came to have the best pitching in the league for many years.”18

Piña was late reporting to the Senators camp in 1970, until manager Ted Williams threatened to fine him $100 a day.19 But when he did arrive, Williams became his benefactor. Although the general public was unaware back then, at least some of the Senators knew that Williams (who spoke some Spanish) had Mexican heritage. They did not know that it was on his mother’s side, though, because Ted almost never spoke of family. Horacio has said that it was not a surrogate father-son relationship, yet the Splendid Splinter may still have seen something of his former self in El Ejote.

Piña described their rapport in ProMex, a San Antonio-based Hispanic sporting monthly of the early ’90s. He told how “Williams became a close friend who helped him adjust to life in the United States. Since Pina didn’t feel very secure about his English, he would get to the ballpark very early. Naturally the manager Williams was also there.” Horacio also learned how to fish from the noted angler. He spoke fondly of “their talks while casting their rods into a tin can inside the dugout. ‘[Williams] would complain about guys like Frank Howard who were making a lot of money and weren’t half as good as he was.’”20

In 2009 Piña added his memories of how Williams would invite him to the movies if a game got called. (“What are you doing?” “Nothing.”) It would be just the two of them, and Ted would buy popcorn and a gallon of milk. They shared a lot of laughs even if they didn’t understand the film. “I really appreciated him. He was a tremendous person and he gave me a job,” said Horacio in summary.

Working strictly in relief, Piña appeared often with the Senators in 1970 (a career-high 61 games) and again in ’71 (56 games). His stints were short by the standards of the day, as he totaled 128⅔ innings pitched. Though he continued to walk a good few batters, he was still generally effective.

Even so, author Thomas Boswell fondly recounted one unflattering (yet funny) memory of an outing at Griffith Stadium. “Once, we saw the Senators’ flamboyant submarine pitcher, Horacio Pina, as he caught his spikes and tripped in mid-delivery. He rolled down the mound in a sideways tangle as though he’d somehow nailed his own hand to the ground. For years, when somebody tried to be too flashy and fell on his face, my mother would intone, ‘Horaaaacio Piiiina.’’’21

Piña stayed with the franchise in 1972 as owner Bob Short moved it to Texas. That season he recorded a career-high 15 saves in 60 games. Though he had earned Ted Williams’ confidence, Horacio said modestly, “I am just a mediocre pitcher. I could not be a starter, but I could go in for a few innings and help the team. A relief pitcher has to throw strikes more than a starter and he has to use his brains more. … I just try to throw strikes aiming at the batter’s weak points.” The same article noted his “quick smile” and “friendly character” — and that he was making more money with Culiacán than he was with the Rangers.22

On November 30 the Rangers traded Piña to Oakland for a former Washington teammate, first baseman Mike Epstein. The A’s sought room in their lineup for Gene Tenace, whose shoulder ailment was limiting his ability to catch.23 The Oakland Tribune took a dim view of the deal — “Epstein [was] surrendered rather cheaply, it seemed”24 – but it worked out well for the A’s. The disgruntled slugger played only 27 games for Texas in ’73 before they peddled him to the Angels, where he struggled for the rest of that season. “Superjew” was out of the majors after just 18 games with California in 1974.

On the other hand, Horacio was pleased. From Culiacán, he said, “Ted Williams was great to me and I was happy in Washington and in Texas, but pitching for the world champions will be something special.”25 He got off to a strong start in the East Bay, with some help from Oakland pitching coach Wes Stock. Bruce Markusen wrote:

“Initially, Pina had also failed to impress Stock, who noted his past inability to handle left-handed batters. Pina, an effective side-arming pitcher against right-handed hitters, seemed unwilling to use that style against lefties. ‘He was coming over the top to left-handers and his ball always was up,’ Stock explained to The Sporting News. ‘His natural motion is side-arm, and his ball sinks when he throws it that way.’

“Stock quickly convinced Pina to rid himself of the overhand delivery and show courage in using his side-winding motion at all times. Pina had been given such advice in the past, but the recommendations never stuck — until now. With his long fingers and large hands, Pina already threw his best pitch, a sinking palmball, more effectively than most pitchers. Pina’s palmball now became lethal to left-handed hitters, as well.”26 He had learned the pitch from bullpen mate Joe Grzenda with the Senators and mastered it in winter ball.27

In later years, Horacio commented, “I believe the submarine ball was a gift that God gave me ever since I started. When I went to the U.S., many people said they wanted me to change that style, but the reality is that they told me, “Forget it, you’re getting outs and that’s why we’re keeping you with us.”28

Piña complemented Rollie Fingers, Darold Knowles, and Paul Lindblad nicely in the Oakland bullpen. He pitched in 47 games (6-3, 2.76) and picked up eight saves. Oddly enough, this was the first season since 1969 in which lefties had a higher batting average against him than righties.

In 2009 Horacio underscored how A’s manager Dick Williams liked discipline. “He was good people but there was a lot of discipline, and that’s why Oakland became champions. He didn’t hang out with the team, just on the field, and outside he was apart.”

He mentioned how Williams gave him chances to pitch, including various save opportunities when Rollie Fingers was not available. For a while, however, he was in Dick’s doghouse. In a key situation against Baltimore, the skipper approached the mound and told him that he didn’t want to see any curves or changeups, just fastballs. Piña disobeyed and gave up a home run. This appears to have been in Oakland on July 16, as aging Brooks Robinson hit a three-run homer in the seventh to give the Orioles a 7-5 lead that they then held.

“Dick Williams got mad. He had me a month [actually 11 days, but no doubt it felt longer], go warm up, sit down, warm up, sit down. He was right, I didn’t pay attention. He told me, ‘Here, what I say goes.’ They told me that for this they could send me to Triple A.”

Finally Piña returned to action on July 27 when Dave Hamilton got knocked out of the box in the first inning at Minnesota, following a doubleheader on the 26th. Williams came in and said, “Only fastballs.” This time Horacio obeyed. In his view, the biggest thing he learned from Williams was his sharp strategy in making changes. “He made some tremendous changes, good for the team and for winning.”

Advancing to the postseason for the first time in the US, Horacio pitched in one game in the AL Championship Series against Baltimore. In Game Two, the Orioles knocked Vida Blue out in the first inning. Piña replaced him and pitched two scoreless innings, though he allowed one inherited runner to score.

The A’s then faced the surprising New York Mets in the World Series. Horacio became the second Mexican to make it to the fall classic, following Bobby Ávila in 1954. In Game Two, Vida Blue was leading 3-2 in the sixth inning but put two runners on with one out. As Joseph Durso of the New York Times put it, “Blue was replaced, briefly and disastrously, by Horacio Pina and his right-handed, underhanded-whip delivery.”29 His first pitch hit Jerry Grote; he then gave up a 10-foot scratch single to Don Hahn. Bud Harrelson followed with a clean single and that was it for Piña. Darold Knowles then entered and got Jim Beauchamp to hit a comebacker that should have been a 1-2-3 double play. Instead, he slipped and threw it away, and two unearned runs were charged to Horacio. The Mets eventually won in 12 innings, 10-7, as Mike Andrews made two errors and became a scapegoat for owner Charles O. Finley.

Piña relieved for three innings in Game Four, which the Mets won 6-1. Mike Andrews, reinstated on the Oakland roster, pinch-hit for him in the eighth inning. Knowles and Fingers were the only relievers whom Dick Williams used after that. When the A’s took Game Seven, though, Horacio pocketed a full winner’s Series share: $24,617.57. He went home to the acclaim of all Mexico.

Not long after the Series ended (December 3), Oakland traded Piña to the Chicago Cubs, re-obtaining Bob Locker. It was a curious swap in a couple of ways. First, Locker was also a side-armer. In addition, “the trading of Locker fulfilled a promise the Cubs had made him when they swapped Billy North to Oakland for the veteran righthander [the previous offseason]. Locker … had said he would not report unless the Cubs promised to trade him back to a Coast club.”30

Charlie Finley, who acted as his own general manager, also apparently liked what Locker had done his first time around with the A’s. Reportedly, however, Dick Williams was “dazed” by the deal, even though Piña had “fallen out of favor” with him. “How could Charlie make that trade?” Williams said. “He says he wants me back as manager and then he goes and trades Pina … [who] is seven years younger.”31 Events would prove the manager mostly right. Locker missed the entire 1974 season after an elbow operation; Oakland then shipped him back to Chicago, along with Darold Knowles and Manny Trillo, for Billy Williams.

Meanwhile, in the National League for the first time, Piña appeared in 34 games for the Cubs in 1974. The team had envisaged him as their short reliever, but there were few save opportunities that year. Most of those went to Oscar Zamora after he was promoted to Chicago in June. Worse, Horacio had a sore shoulder (something that had also bothered him during 1973). On July 28 the Cubs traded him to the California Angels for lefty-hitting catcher Rick Stelmaszek, a Chicago native. Pitching under Dick Williams once again, he saw little action the rest of the way, pitching just 11⅓ innings in 11 games.

At the end of spring training 1975, the Angels released Piña (who had reported late). The A’s reacquired him on waivers, but allegedly he refused to report because he didn’t want to pitch in the minors.32 According to Horacio, though, he was told that his fastball wasn’t what it used to be. In addition, he refused to take a cortisone shot.33

Still not yet 30, the pitcher returned home to Matamoros. He wanted 40,000 pesos (US $3,200 at the prevailing exchange rate) and a Dodge Royal Monaco car to play in the Mexican League. His local team, Unión Laguna, wouldn’t meet those conditions — but Aguascalientes did.34 He paid dividends almost immediately, throwing a seven-inning no-hitter at Ciudad Juárez on May 1, 1975.

Piña would spend the next five seasons with the Rieleros, largely as a starter but also coming out of the pen, which was his primary role in 1977. From 1975 to 1977 he was only one game over .500 (32-31), but his ERAs were excellent, including a league-leading 1.70 in ’77.

Horacio’s second LMP championship with Culiacán came in the winter of 1977-78, and he got to play in the 1978 Caribbean Series in Mazatlán. Host nation Mexico went just 1-5, though, with Piña losing one game in relief to the Dominican Republic. His time with the Tomateros also ended after a run-in with Juan Manuel Ley, eldest son of Juan Ley Fong and the team’s co-founder. “Three other players and I demanded of Chino Ley that he put us up on the beach and that he give us the $40 per diem that he gave the foreign ballplayers. But he got pissed off and ran us off the club. He sent me to Mexicali.”35

Piña’s greatest game came that summer in Aguascalientes, at Estadio Alberto Romo Chávez before a crowd of more than 25,000. He was aware he had a no-hitter — when the manager’s young sons told him, he replied, “Go over there and bring me a coffee.” However, he had no idea that the 86-pitch masterpiece was a perfect game, only the second of nine innings in league history. He was perhaps most pleased that he had set a career high with his 17th victory.36 Horacio followed up by pitching six more perfect innings in his next start.37 He capped his career year by helping the Rieleros win the Mexican League championship, although he lost a duel in the finals to Unión Laguna’s ace, Antonio Polloreno.38

That September 14, the Philadelphia Phillies purchased Piña’s contract. Rubén Amaro, Sr., then a Latin American scout with the Phillies, recommended him.39 Horacio pitched in two games down the stretch for the NL East winners, but he was not on the postseason roster. After Philadelphia lost the NLCS to the Los Angeles Dodgers, they returned him to Aguascalientes.

In February 1979 one US article quoted Phillies manager Danny Ozark as unconcerned that Piña was not yet in camp,40 suggesting that at some level he was still in the club’s plans. He stayed with the Rieleros, though, and had a decent year (13-9, 2.80). Horacio’s last full season in the pros was 1980; for the Yucatán Leones, he was 9-8, 1.51. That winter, however, he tore his rotator cuff while playing for Guaymas. Even though Dr. Eluterio Valencia operated, he knew it was a career-ender as it happened.41

Piña’s final summer statistics in Mexico were 100 wins, 68 losses, and a 2.35 ERA. He started 160 of his 235 appearances, pitching 98 complete games and 24 shutouts. In 2007 the Mexican Pacific League celebrated its 50th anniversary and issued a list of the top 50 players in its history. One of those names was Horacio Piña.

After retiring, Piña served two seasons as a pitching coach for Unión Laguna.42 He then stayed home in Matamoros. In addition to drawing his big-league pension, Horacio established a cantina alongside his house, together with one of his brothers. In his leisure time, he still spent many hours fishing.43

Piña and his wife, Zoila Ávila, whom he married in Matamoros in 1967, had six children: Horacio, Hilda Patricia, Rosa Isela, Roberto, Yazmín Anel, and José Iván. Sad to relate, they also lost an infant who was less than a month old. Horacio was away playing in the US at the time and he did not even know until the burial had already taken place. The same happened when his grandmother died. Piña suffered another tragedy when the son he had with a woman in Aguascalientes died at age 12 in a freak horseback riding accident. (He also had a daughter from this relationship.)44

In March 2009 Matamoros re-inaugurated La Unidad Deportiva Horacio Piña, the multisport facility that honors the town’s best-known athlete. After several years of discussion, the center received much-needed government funding for repairs and upgrades, as time and the elements had taken a severe toll over three decades of use.45 The young men of the city also play baseball in La Liga Municipal Horacio Piña.

By his early 60s, the once-skinny Ejote had put on a pleasing amount of weight (he liked his Corona beer). He remained lively, full of laughter, and interested in baseball. For example, he commented in 2007 that steroids don’t make the ballplayer. “I’m going to put it to you very simply. To bat, first you have to hit the ball, and to get outs, first you have to throw strikes. Steroids don’t give you either of those things.”46

Looking back on his time in the majors — specifically with Oakland — Piña said in 2008, “They taught me to give it everything I’ve got, not to be wishy-washy, always give it your best shot, like the boxers.”47

Last revised: July 28, 2015

This article originally appeared in “Mustaches and Mayhem: Charlie O’s Three Time Champions: The Oakland Athletics: 1972-74″ (SABR, 2015), edited by Chip Greene. It also appeared in “1972 Texas Rangers: The Team that Couldn’t Hit ” (SABR, 2019), edited by Steve West and Bill Nowlin.

Acknowledgments

Francisco Rodríguez Lozano’s article (“Horacio Piña: El hijo pródigo de Matamoros”), based on an interview at home with Piña, was originally published in the magazine Semanario Vanguardia (Saltillo, Coahuila, Mexico), August 4, 2008. It may be found with accompanying photos at semanariocoahuila.com/pdf_sem/semanario_131.pdf and also on Paco’s blog (http://pacorolo.blogspot.com/2009/08/el-hijo-prodigo-de-matamoros.html). Paco also re-interviewed Piña on November 25, 2009, and December 3, 2009, providing additional input.

Thanks also to Fernando Ballesteros of the Puro Béisbol website.

Sources

paperofrecord.com (other small pieces of information from The Sporting News)

retrosheet.org

ligadelpacifico.mx

salondelafama.com.mx

Treto Cisneros, Pedro, editor, Enciclopedia del Béisbol Mexicano(Revistas Deportivas, S.A. de C.V., 1998).

Bjarkman, Peter, Diamonds Around the Globe: The Encyclopedia of International Baseball(Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2005).

Araujo Bojórquez, Alfonso, Series del Caribe: narraciones y estadísticas, 1949-2001(Colegio de Bachilleres del Estado de Sinaloa, 2002).

Photo Credits

Horacio Piña collection

Notes

1 “Pina Is Articulate Moundsman.” Associated Press, August 11, 1972 (information on number of siblings and father’s occupation); Rodríguez Lozano, Francisco, “Horacio Piña: El hijo pródigo de Matamoros.” The photo of a plaque in Matamoros, on the blog version of Rodríguez’s story, showed Piña’s parents’ names.

5 Fernando Ballesteros, “Desestima Piña los esteroides.” Puro Béisbol website (purobeisbol.com.mx/content/blogcategory/10/28/), published in 2007.

11 Russell Schneider, “Gabe Nabs Another Tamale From Mexico in Horacio Pina,” The Sporting News, September 7, 1968, 17.

16 Raul Flores and Mario Longoria, “Mexican Hall of Famer — Horacio Pina,” ProMex, issue unknown, 1990.

17 Russell Schneider, “Tribe Finds Relief From Bullpen Ache,” The Sporting News, December 20, 1969: 40.

19 Merrell Whittlesey, “Hot Tamales — Rodriguez and Pina Fuel Nats,” The Sporting News, May 23, 1970: 33. During the 1970 season, before he was traded to Detroit, fellow Mexican Aurelio Rodríguez was Horacio’s roommate both in a Washington hotel and on the road.

21 “The Church of Baseball,” in Geoffrey C. Ward and Ken Burns,Baseball: An Illustrated History(New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1994), 191. In another telling of the story (Los Angeles Times, May 13, 2001: D-2), Boswell had a gust of wind blowing Piña sideways.

23 Ron Bergman, “Epstein Exit Traced to Tenace Shoulder Ailment,” The Sporting News, December 23, 1972: 37.

25 Tomás Morales, “Trade to A’s Pleases Mexican Starter Pina,” The Sporting News, January 6, 1973: 47.

27 Ron Bergman, “Athletics Avoid Deep Water When Horacio Is on Bridge,” The Sporting News, May 19, 1973: 13.

29 Joseph Durso, “Mets Get 4 Runs in 12th to Beat A’s, 10-7, and Even Series at 1-1,” New York Times, October 15, 1973: 1.

31 Ron Bergman, “Williams Dazed by Finley Deal for Locker,” The Sporting News, December 29, 1973: 29.

37 Sergio Luis Rosas, “Recibe homenaje Horacio ‘Ejote’ Piña,” El Siglo de Torreón, November 4, 2007.

Full Name

Horacio Piña Garcia

Born

March 12, 1945 at Matamoros, Coahuila (Mexico)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.