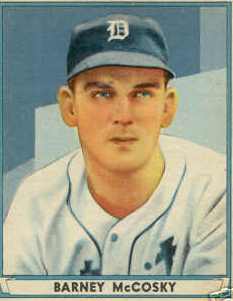

Barney McCosky

William Barney McCosky, a Pennsylvania native who grew up in Detroit, was a talented and speedy all-around center fielder who broke into the major leagues with a bang in 1939, hitting .311 for the Detroit Tigers. Barney, who stood 6-feet-1 and weighed 185 pounds in his prime, threw right and batted left, and he did both with skill, accuracy, and grace. So well did he perform that by mid-July of his rookie year, the highly respected Joe Williams, the sports columnist for the New York World-Telegram, named McCosky to his “Major [League] All-Recruit Team.” Williams picked three American Leaguers to his all-rookie outfield: Boston’s Ted Williams, batting over .300 at that point with 15 home runs and 80 RBIs, in left field; New York’s Charlie Keller, who finished the year averaging .334 with 11 homers and 83 RBIs, in right; and McCosky in center. Despite 11 years in the major leagues and a career batting average of over .300, that third rookie became a virtual unknown, except to longtime fans of the Tigers and the Philadelphia Athletics. Still, McCosky owned one of the sweetest swings in baseball, and in many ways his career compares favorably to that of Yankees great Joe DiMaggio. Many big leaguers of the 1940s suffered major career interruptions during World War II, but Barney suffered a second disruption. The aftermath of a back injury suffered on June 15, 1948, was spinal fusion surgery in 1949, and though he played for four seasons after the operation, he was never the same.

William Barney McCosky, a Pennsylvania native who grew up in Detroit, was a talented and speedy all-around center fielder who broke into the major leagues with a bang in 1939, hitting .311 for the Detroit Tigers. Barney, who stood 6-feet-1 and weighed 185 pounds in his prime, threw right and batted left, and he did both with skill, accuracy, and grace. So well did he perform that by mid-July of his rookie year, the highly respected Joe Williams, the sports columnist for the New York World-Telegram, named McCosky to his “Major [League] All-Recruit Team.” Williams picked three American Leaguers to his all-rookie outfield: Boston’s Ted Williams, batting over .300 at that point with 15 home runs and 80 RBIs, in left field; New York’s Charlie Keller, who finished the year averaging .334 with 11 homers and 83 RBIs, in right; and McCosky in center. Despite 11 years in the major leagues and a career batting average of over .300, that third rookie became a virtual unknown, except to longtime fans of the Tigers and the Philadelphia Athletics. Still, McCosky owned one of the sweetest swings in baseball, and in many ways his career compares favorably to that of Yankees great Joe DiMaggio. Many big leaguers of the 1940s suffered major career interruptions during World War II, but Barney suffered a second disruption. The aftermath of a back injury suffered on June 15, 1948, was spinal fusion surgery in 1949, and though he played for four seasons after the operation, he was never the same.

McCosky, a modest, energetic, likeable young man with a smiling disposition, wavy brown hair, and pale blue eyes, was popular with his Detroit teammates. The hometown hero batted .447 in his first nine big-league games and he never fell below .300 in 1939, making a big hit with the Briggs Stadium bleacherites, who loved cheering for the exploits of the local star. By mid-1940, with the world heading toward war, Michigan’s factories gearing up for war production, and the Tigers fighting for the American League pennant against the Cleveland Indians and the defending champion Yankees, the Detroit papers, columnist Jerry Green later pointed out, were comparing the 22-year-old McCosky to the great Ty Cobb in “style, speed, and ability.”

The youngest of nine children in a Lithuanian-Polish working-class family, Barney was born in the mining town of Coal Run, Pennsylvania, on April 11, 1917, one week after Congress voted for the United States to enter World War I. When he was 5, his father, seeking a job in Detroit’s booming auto industry, moved his family to the Motor City. A youngster who thrived on baseball and basketball, Barney was playing the national pastime before the Great Depression began in 1930. As a sandlotter, he dreamed of playing in the major leagues, and his hero was Charlie Gehringer, the Hall of Fame second baseman who starred for the Tigers from 1926 to 1942. The youth copied Gehringer’s left-handed stance, grip, and smooth swing while playing American Legion ball in the summers. Moved to the outfield by Southwestern High’s coach as a sophomore, McCosky was spotted by Aloysius “Wish” Egan, the Tigers’ chief scout. Indeed, Barney recalled batting .457 as a junior and .727 as a senior, but he wanted to go to college. Egan and the Tigers made the 18-year-old an offer he couldn’t refuse: He would play one year in the minors, and if he didn’t perform well, Detroit would pay for his four years of college.

The deal paid off for the Tigers after McCosky climbed through the club’s farm system in three years. The teenager started the 1936 season with 20 games at Beaumont of the Class A1 Texas League, where he batted .227 and made a few errors. The Tigers sent him to Charleston, West Virginia, of the Class C Middle Atlantic League. The speedy Detroiter starred in center field for the second-place Senators, making the loop’s all-star team and pacing all hitters with a .400 mark. Talking about that season in a 1991 interview with SABR member Norman Macht, McCosky recalled earning $150 a month in C-ball; hitting well but making a “few mistakes” in the outfield; paying room and board of $7 a week, and traveling everywhere by bus; and playing mostly night games under “candlelight”! In those years, Barney said, you learned from your mistakes. You didn’t get much coaching, so you were on your own to improve.

McCosky spent the next two seasons at Beaumont, at that time the main training ground for future Tigers. Beaumont was about 25 miles from the Gulf of Mexico in the southeastern corner of Texas, and there the Exporters sweated through hot and humid summers wearing dark red woolen uniforms. In 1937, Barney hit .311, but Fort Worth’s Homer Peel led the circuit with a .370 average. Still, McCosky paced the league in four categories: hits with 201, runs with 116, triples with 20, and outfield putouts with 412 in 158 games. In 1938, the Detroiter missed five weeks early in the season with a broken ankle. After the ankle healed, he enjoyed a good season, batting .302 in 133 games, with 78 runs, 156 hits, 18 doubles, six triples, but no home runs (he had hit one homer in 1937). However, McCosky batted leadoff or second most of the time, so his lack of home-run power didn’t matter to the Tigers. He could, and did, slam doubles and triples into the gaps in right-center and left-center, and his speed made him a threat on the bases.

McCosky went to spring training with Detroit in 1939, but he figured the parent club would send him to the American Association for another year of seasoning. Indeed, he did not hit well in the early exhibition games. Near the end of March, Tigers manager Del Baker was deciding between two left-handed-batting rookies, McCosky and Frank Secory, who had hit .323 at Beaumont in 1938. Taking a last look at Barney, Baker put the 21-year-old in the leadoff spot against Brooklyn’s veteran right-hander Whitlow Wyatt. The Michigan rookie went 3-for-4 with a double, a triple, and a single. That evening, McCosky recalled in 1991, Baker told him he had made the team. Thereafter, Barney was a changed player: His tenseness was gone, his fielding improved, and he hit over .400 for the rest of the spring. The first graduate of Detroit’s sandlots and high schools to play for the Tigers, McCosky displayed his batwork on Opening Day against the Chicago White Sox, going 2-for-3 with a pair of singles. He continued to hit well, partly because he swung only at good pitches and because he rarely tried to slug the ball.

“Rare days that have seen McCosky stopped by a [Bob] Feller or a [Red] Ruffing have served to emphasize a quality responsible for his consistent success,” Doc Greene, sports editor of the Detroit News, wrote for a column in The Sporting News datelined July 8, 1939. “Failure does not discourage him. Tomorrow always is another day that he greets with determination and poise, unmindful of pop flies or strikeouts that may have spoiled a previous afternoon’s work.” As if to second that motion, Clark Griffith, owner of the Washington Senators, declared McCosky his choice for “Recruit of the Year” (the Rookie of the Year award was not created until 1947).

Baker’s Tigers, however, fell to the second division for the first time in six years, finishing fifth in 1939 with an 81-73 ledger, 26½ games behind the pennant-winning Yankees. Still, Detroit fielded a good-hitting team. Charley Gehringer, still the anchor to the infield in his 14th full season with the Tigers, paced the club with a .325 average, including 16 home runs and 86 RBI. Hank Greenberg, the first baseman, who had clubbed 58 home runs in 1938, ranked second behind Gehringer in 1939 with a .312 batting average and led the team with 33 homers and 112 RBIs. Batting leadoff, McCosky was Detroit’s third-best hitter at .311. He showed power in the alleys, hitting 33 doubles and 14 triples, and he hit four home runs while producing 58 RBIs. Powerful Rudy York, who caught in 67 games and played 19 games at first base, ranked fourth with a .307 mark, but the right-handed hitter belted 20 home runs and drove in 68 runners. Also, burly Buck Newsom, arriving in a trade from the St. Louis Browns, led Detroit’s staff with a 20-11 mark. Newsom threw a hopping fastball and a slider, but no curve, McCosky recalled. Veteran curveballer Tommy Bridges posted the next best record at 17-7.

Reflecting on that season more than 50 years later, McCosky said that Detroit was loaded with veteran players who knew one another. He didn’t drink or play cards, two of the favorite pastimes of most major leaguers, so he usually kept to himself. When the Tigers played at home, Barney, who was single, lived with his family. On the road, he roomed with rookie right-hander Paul “Dizzy” Trout. Gehringer, Barney’s hero, took the Detroiter under his wing. Also, teams traveled by train in those years, and spending half of the season on road trips helped foster camaraderie, and Barney got to know all of the Tigers as the 1939 season progressed

As a hitter, McCosky remembered planting his front foot up in the batter’s box. That kept him from lifting the front foot too soon or striding too far on a pitch. If he had a question, Barney would ask Gehringer to watch him bat, but the veteran second baseman would often say, “Keep going.” Also, McCosky said, “I would just try to meet the ball, not swing hard, just like a pepper game.” He attributed his good hitting to his stance and his bat control. That year the recruit signed for $500 a month, but due to his success, Detroit raised him to $5,000 a year on June 15.

McCosky remembered being nervous on Opening Day in 1939, Tuesday, April 18, before 47,000 shivering fans on a chilly, windy, rainy day at Briggs Stadium. The Tigers defeated the White Sox, 6-1, and Barney collected two singles and scored one run in three at-bats. In his first major-league at-bat, he faced Chicago’s John Rigney (15-8 with a 3.70 ERA in 1939). “I got up to the plate leading off, and regardless of where the pitch was, I was taking it,” he recalled. “I took the ball—it was high, under my chin. With that [pitch], everything just dropped [into place]. It seemed like I relaxed, and I was ready.” He hit a single in his second at-bat. He remembered the same nervous feeling in the 1940 World Series, but after the first pitch, he was ready.

After his impressive rookie season, McCosky enjoyed a career year in 1940, hitting .340, pacing the league with 19 triples (the most by any Tiger since then), and helping Detroit into the World Series against Cincinnati. After some key trades, the Tigers, compiling a record of 90-64, finished one game ahead of the Cleveland Indians and two ahead of the Yankees. Detroit posted the AL’s best batting mark at .286 and scored the most runs, 888. Greenberg, shifted to left field by Del Baker during spring training so York could play first base, shared Tigers hitting honors with McCosky, also batting .340. Greenberg didn’t like the switch at first, McCosky remembered, but it worked so well that after the season, Hank paid for a new suit for Barney from Greenberg’s personal tailor at the Cadillac Hotel. Later the first Jewish player inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Greenberg, who stood 6-feet-4 and weighed 210 pounds, led the AL with 41 home runs. Close behind was Rudy York, who was reborn at first base—his position in the minors before arriving with Detroit in 1937. York batted .316, slugged 33 homers and 46 doubles, second only to Greenberg, and drove home 134 runners, also next to Greenberg. In addition, Charley Gehringer overcame back problems to average .313 with 10 home runs and 81 RBIs; catcher Billy Sullivan, traded by the Browns, averaged .309; and Pinky Higgins, acquired from the Red Sox, hit .271 with 13 home runs and 76 RBIs.

On the mound, Newsom again led Motor City club with a 21-5 record, but former ace Lynwood (Schoolboy) Rowe, the 6-foot-4½-inch-tall Texan who was coming back from arm woes (Rowe was 10-12 in 1939), produced a 16-3 ledger, Tommy Bridges was 12-9, and Detroiter and future Hall of Fame southpaw Hal Newhouser, working his first full season, went 9-9. Also, 6-foot-4 reliever Al Benton, who threw a “heavy” sinker, posted a 6-10 record, pitching 79 1/3 innings in 42 appearances, finishing 35 games, and leading the league with 17 saves. Further, the Tigers got at least two victories from seven other pitchers, notably a pair from right-handed rookie Floyd Giebell. Leading the Indians by two games, Detroit arrived in Cleveland for the final three games of the season. Baker opened with Giebell. On September 27, 1940, the 6-foot-2½ West Virginia native hurled a shutout, spacing six singles to defeat fireballing Bob Feller, 2-0. Feller allowed just three hits, but in the fourth inning, Gehringer walked and York clouted a two-run homer that clinched the pennant. Giebell, however, had been recalled from Buffalo of the Double-A International League after September 1, making him ineligible for the World Series.

The Indians won the final two games of the series by one run each, but it hardly mattered, because the surprising Tigers had battled their way into the World Series for the third time in seven years. Experts like the sportswriter Grantland Rice figured defending National League champion Cincinnati had the better pitching staff, anchored by Bucky Walters, who posted NL bests with his 22-10 record and 2.48 ERA, and Paul Derringer, with a 20-12 record and a 3.06 ERA. On the other hand, most sportswriters agreed that if the fall classic hinged on hitting, Detroit could win. In particular, observed New York scribe Judson Bailey, the Tigers had the better outfield, featuring two .340 hitters, the slugging Greenberg in left and McCosky, the “defense kingpin,” in center field. In right, Baker had two choices: veteran Pete Fox, a right-handed batter who had hit well for Detroit in the 1934 and 1935 World Series, averaged .289 with five home runs and 48 RBIs in 1940, and left-handed-hitting Bruce Campbell, a veteran flychaser acquired from Cleveland, batted .283 with 8 homers and 44 RBIs. Also, Baker had the majors’ best pitcher, Buck Newsom, who enjoyed his third straight 20-win season.

McCosky made an important contribution, but the World Series was settled largely by pitching:

· Game One, at Cincinnati’s Crosley Field – won by Detroit, 7-2: McCosky, batting second after shortstop Dick Bartell, went 2-for-5 with one RBI. Newsom tossed an eight-hitter, and the Tigers knocked Paul Derringer out of the box with a five-run second, including McCosky’s RBI single. The visitors racked up ten hits and coasted to the victory, as Bartell, McCosky, York, and right fielder Campbell, who homered, each had two hits, and Bartell, Campbell, and Higgins batted in two runs apiece. Sadly, Newsom’s father died the night of the victory

· Game Two, at Crosley – won by Cincinnati, 5-3: McCosky was hitless in two trips, but he walked twice and scored Detroit’s second run. The Tigers scored twice in the first as Walters allowed walks to Bartell and McCosky, Gehringer’s RBI single, and Greenberg’s double-play grounder. Walters hurled a three-hitter, but Rowe showed none of his old speed, and left fielder Jim Ripple reached him for a two-run homer. Rowe departed in the fourth, rookie Johnny Gorsica (7-7 with 4.33 ERA in 1940) blanked the Reds on just one hit, but Detroit scored just one more run

· Game Three, at Detroit’s Briggs Stadium – won by Detroit, 7-4: McCosky went 2-for-4 and scored once. In front of the hometown fans, the Tigers’ potent offense provided 13 hits. Detroit tied the score at 1-1 in the fourth when McCosky singled, worked the hit-and-run with Gehringer, and scored on Greenberg’s double-play bouncer. Bridges pitched the route, yielding ten hits, but never trailed. In the seventh, York and Higgins each blasted two-run homers for a 5-1 lead. Bridges gave up one run in the eighth and two in the ninth, but Detroit counted twice in the eighth for a 7-2 lead

· Game Four, at Briggs – won by Cincinnati, 5-2: McCosky went 1-for-2 with two walks and tallied once. Derringer pitched a five-hitter for the victory, but Dizzy Trout (3-7 with 4.47 ERA in 1940) was chased from the box in the third after the Reds scored once to lead, 3-0. McCosky’s speed counted in the third when he walked, raced to second on Gehringer’s groundout to short, and tallied on Greenberg’s double to left, cutting the lead to 3-1. The Tigers scored once in the sixth, after which Derringer hurled shutout ball, and the Reds clinched the win by adding single runs in the fourth and the eighth

· Game Five, at Briggs – won by Detroit, 8-0: McCosky went 2-for-2 with two walks and scored twice. Pitching on emotion, Newsom tossed a three-hit shutout, and the Tigers roared with a 13-hit attack. Detroit scored seven runs off Junior Thompson before he was removed in the fourth. Greenberg and Campbell rapped three hits each, including Hank’s tremendous home run in the third with McCosky and Gehringer aboard. McCosky, Gehringer, and Campbell added two hits each, and Newsom did the rest

· Game Six, at Crosley – won by Cincinnati, 4-0: McCosky, who averaged .304 (7-for-23 with five runs, one double, and one RBI) for the seven-game series, went hitless in four trips. Walters tossed a five-hitter and batted in two runs, one with a solo home run. Rowe lasted just one-third of an inning, surrendering two runs on four hits before Baker removed him. Gorsica and Fred Hutchinson (3-7 with a 5.68 ERA in 1940) allowed one run apiece, but the Tigers couldn’t solve Walters’ slants

· Game Seven, at Crosley – won by Cincinnati, 2-1: McCosky was hitless in three trips but drew one walk. Newsom pitched against Derringer on one day’s rest, while Derringer had two days. Detroit scored once in the third when Billy Sullivan beat out an infield hit and took second on Newsom’s sacrifice bunt. After Bartell popped out, McCosky walked. Gehringer smashed a shot to third, and Billy Werber knocked it down but threw late to first, as Sullivan hustled around to score. Newsom made the lead stand up until the seventh, when Frank McCormick, the Reds’ top power threat with 19 home runs and 127 RBIs, doubled to left. Ripple doubled off the top of the right-field screen, and McCormick, who hesitated at second and also at third base, scored when Bartell took the relay from Campbell but didn’t fire home—crowd noise evidently kept the shortstop from hearing Sullivan’s cries to throw the ball. After a sacrifice bunt and an intentional pass, shortstop Billy Myers drove in the game-winning run with a long fly to McCosky in front of the center-field wall

McCosky, batting second as he had all season, contributed a strong series with his .304 mark, the fourth best average among Tigers, along with good baserunning and fine fielding (“a great all-around player,” John Kieran of the New York Times called him), but it wasn’t enough. Newsom was Detroit’s ace with a ledger of 2-1 and a 1.38 ERA, but Schoolboy Rowe flopped with two losses and a huge 17.18 ERA. Bruce Campbell led Detroit at bat, hitting .360 with a double, a home run, and five runs batted in. Greenberg hit .357 with two doubles, a triple, and a home run, and he drove home six runs. Pinky Higgins batted .333 and tied McCosky with a team-high five runs, hitting three doubles, a triple, and a homer, and tying Greenberg by batting in six runs. Dick Bartell hit .269 with two doubles and three RBIs, but Rudy York batted only .231, collecting a double and a triple among his six hits and batting in two runs.

In 1940, the year German and Italian fascist forces overwhelmed Western Europe but England survived the German Luftwaffe’s air raids in the Battle of Britain, McCosky, a fan favorite in Detroit, became an established star in the American League. Further, he gave the Tigers two more stellar years before joining the Navy. During his seven years as a regular, Barney averaged a remarkably consistent .319, and he missed the .300 mark only in 1942.

Although McCosky enjoyed another good year on the diamond in 1941, baseball headlines that season focused on Joe DiMaggio’s 56-game hitting streak, Ted Williams’s .406 season, and Hank Greenberg’s induction into the Army. Detroit expected to contend again, but fell to fifth with a 75-79 record. The big blow occurred when Greenberg, the league’s Most Valuable Player in 1940, was drafted in April and sworn into the Army on May 7. At the time, Hank was hitting just .269 in 19 games, but he slugged his only two home runs of the year in a 7-4 victory over the Yankees on May 6, his last day as a civilian. Despite his departure, Greenberg’s importance to baseball was such that he made headlines at Michigan’s Fort Custer, for example, when he was promoted to private first class, corporal, and sergeant. On December 5, he was mustered out of the Army under a recent ruling that said men over 28 were ineligible to go overseas. Two days later, on December 7, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor and propelled the United States into World War II, and Greenberg said he would re-enlist for the duration, stating, “We are in trouble and there is only one thing to do—return to the service.”

McCosky averaged .324 in 127 games in 1941, hitting 25 doubles, eight triples, and three home runs. Also, he suffered his first major injury, on May 11 against the White Sox at Chicago’s Comiskey Park, when he wrenched his back rounding second base, and teammates had to carry him from the field. Barney was treated at Detroit’s Ford Hospital for several days, and he returned to the lineup in early June. Rookie Pat Mullin, a left-handed batter who hit .345 with five homers and 23 RBIs in 54 games in 1941, took over center field, until he broke his collarbone in early July. McCosky returned to center, and Del Baker used him to bat third or fourth. Barney’s highlights included lifting Detroit over Philadelphia, 3-2, on July 15, producing a double, a home run, and two RBIs. On August 7, he led the Tigers over Bob Feller and the Indians, 4-3, rapping three singles in five trips and scoring the game-winning run in the 13th inning. On August 20, he went 2-for-5 with an RBI single in the tenth that won the game, 1-0. On August 22 at home, McCosky’s only hit was decisive: a ninth-inning three-run shot into the upper deck in right field for a 5-4 victory over Washington. Regardless, he seemed to labor in obscurity. “In the fuss and fanfare of the induction of Hank Greenberg into the Army,” commented Associated Press cartoonist Thomas (Pap) Paprocki in a story dated August 1, 1941, “Barney McCosky’s fine work for the Detroit Tigers in the outfield and at the plate has been almost completely overlooked.”

In 1942, with the US fully committed to fighting against the Japanese in the Pacific and the Germans and Italians on the other side of the world, McCosky tried to lift the Tigers by focusing more on hitting the long ball, but Detroit remained in fifth place and his average slipped to .293, still the best mark among regulars on the team. Avoiding injuries, he played the entire 154 games, usually batting in third or fourth. Barney stepped up to bat 680 times, his second most plate appearances (he appeared 692 times as a rookie), drawing 68 walks, fanning 37 times, and producing 176 hits, including 28 doubles, 11 triples, and a career-best seven four-baggers. Baseball, however, now revolved around the war, and the manpower drain from the major and minor leagues was affecting the national pastime. Detroit fashioned a 73-81 mark, 30 games below the pennant-winning Yankees. The Tigers had many veterans, but Baker also played several younger players. Besides McCosky, other regulars included Ned Harris, a second-year outfielder who batted .271 in 143 games, with nine home runs and 45 RBIs; Pinky Higgins, who hit .267 in 143 games, with 11 home runs and 79 RBIs; Doc Cramer, a seasoned flychaser who came from Washington in a trade, hit .263 in 151 games with 43 RBIs, but no home runs. Showing his power, Rudy York averaged .260 in 153 games and posted teams highs of 21 homers and 90 RBIs.

On December 10, 1942, just over a year after the Pearl Harbor attack, McCosky was inducted into the Navy, making him the 15th Tiger to enter the armed forces. He served until October 1945, but was unable to return home in time to join his teammates as they defeated the Chicago Cubs in a seven-game World Series. McCosky started out at the Great Lakes Naval Training Center, north of Chicago, and he spent time at the Bainbridge, Maryland, Naval Base for advanced training. Later, he was stationed in Hawaii and elsewhere in the Pacific. Wherever he was stationed, he became a recreation specialist, and as he recalled, “We had to give exercises, umpire ballgames, set up basketball tournaments, be instructors, all this stuff. Everybody played hard, and we really enjoyed playing out there [in the Pacific Theater].” Also, like most big leaguers, he played service ball, notably in Hawaii in 1944. During one season in Honolulu, McCosky recalled leading the league with 17 homers, but he hit only .220. Still, players won a free war bond for each four-bagger, and, he said, “I was going for the downs!”

World War II ended with the surrender of Japan in August 1945, and the US began demobilizing the economy and the armed forces, meaning that a host of older and younger players back from the service traveled to spring training in 1946. McCosky took the train from his home in Dearborn, outside Detroit, to the Tigers’ camp at Lakeland, Florida. Like many ballplayers, he was rusty after three years in the Navy. He made the Tigers’ roster (a federal law required major-league teams, like all employers, to give prewar players their roster spot for at least 30 days), but McCosky started slowly, averaging .198 in 25 games. Detroit had youthful outfielders, including Pat Mullin, who hit .246 with three homers and 35 RBIs in 1946, and 6-foot-2 rookie Hoot Evers, a right-handed batter who averaged .266 with four homers and 33 RBIs. The Tigers, however, needed a better third baseman than Jimmy Outlaw, who played the position capably for all seven games of the 1945 World Series, but hit only .179 (he went 5-for-28 with 3 RBIs). On May 28, George Trautman, Detroit’s general manager, announced the trade of McCosky, 28, for George Kell, 23. Kell, 4-F in wartime, batted .268 and .272, respectively, during the 1944 and 1945 seasons, but he was a fine third baseman. “As a prewar baseball name, McCosky stands out,” concluded New York scribe Dan Daniel. “As an actual asset, he is of doubtful worth. Barney is suffering from a leg injury which is said to be chronic. His Detroit batting average this season is under .200.” Calling Kell a “far better fielder” than most realized, Daniel pointed out that the Swifton, Arkansas, native led AL third sackers in assists with 345 and in putouts with 186 in 1945.

Years later, McCosky called the trade a “shock.” At the time, he had a sore ankle from rolling over his ankle rounding third base, so he could not run as well as usual. That afternoon in the locker room at Briggs Stadium, one of the coaches told him, “You’ve just been traded to Philadelphia.”

After the trade, McCosky moved to the last-place Athletics, found an apartment, got married a month later, and rejuvenated his career. His fiancée was Jane Malicki, a Detroit girl he had known for years. Speaking in a 1996 interview, Jane said, “Our friendship developed into a serious relationship through the mail during World War II while Barney was in the South Pacific and I was at Michigan State. Truthfully, I focused on him much before that as a high-school teenager, when he and my father used to hunt and fish together. Since there was a seven-year age difference, he considered me a youngster. With the news of his trade, we canceled our wedding plans for October and were married on June 19, eleven days after my graduation from MSU. This year we celebrated our 50th anniversary at a gathering of family and friends, many of them former teammates. …. Virgil Trucks, Joe Ginsberg, Joe Coleman, Ike Delock.”

For the remainder of the 1946 season, McCosky’s hitting was as good as ever, but he had occasional back problems. For A’s fans, the popular Kell looked great in Detroit, hitting .327 for the rest of the season, and .322 overall. More important, Kell, who later won the hearts of millions as a down-home broadcaster for the Tigers, went on to a Hall of Fame career, hitting .306 lifetime, while McCosky, even though he hit .312 lifetime, later would be known as the player Detroit traded to get Kell. In 1946, Barney averaged .318, but he easily topped the A’s by hitting a sizzling .354 in 92 games, contributing 17 doubles, four triples, one homer, and 34 RBIs. Typical of his good batting eye, Barney drew 43 bases on balls but fanned only 13 times. The club’s only other .300 hitter was Czechoslovak-born outfielder Elmer Valo, who hit .307. McCosky’s erstwhile teammates in Detroit ranked second behind the Yankees with a 92-62 record, but the A’s finished in the AL basement with a 49-105 ledger. Philadelphia struggled to win all season long, but the pitching and hitting fell apart in August and September, when the A’s recorded records of 4-19 and 7-18, respectively. For McCosky, life in the City of Brotherly Love meant more obscurity than he had found in Detroit, where the Tigers featured sluggers like Greenberg and York and pitchers with winning records.

The cash-strapped Athletics owner, Connie Mack, was trying to rebuild his team. In 1947, the year Jackie Robinson crossed the color line in major-league baseball, the A’s, thanks to key acquisitions like rookie Ferris Fain at first base and NL veteran Eddie Joost at shortstop, as well as improved pitching, the Athletics climbed as high as third place and finished fifth with a 78-76 record, the team’s first winning record since 1933. Mack shifted the speedy Sam Chapman, who led the team with 14 homers, to center, sent the good-hitting McCosky, who had lost some speed, to left, and kept Valo in right. The infield featured Joost, the stabilizer, at shortstop, Pete Suder at second, Fain fielding well and hitting .291 with 71 RBIs at first, and Hank Majeski, acquired from the Yankees, hitting .280 with 72 RBIs at third base. Backed by better hitting, better fielding, and the solid Buddy Rosar handling the staff, Philadelphia got good seasons out of Phil Marchildon, who went 19-9 with a 3.22 ERA; Dick Fowler, who was 12-11 with a 2.81 ERA; rookie Bill McCahan, one of Mack’s Duke University products, who was 10-5 with a 3.32 ERA and pitched a no-hitter against Washington on September 3; and Russ Christopher, who finished 38 of the 44 games that he pitched, went 10-7 with a 2.90 ERA, and had 12 saves.

The 1947 season also featured McCosky’s duel with Ted Williams for the batting championship, eventually won by Teddy Ballgame with an MVP-like performance of .343, plus league highs of 32 home runs and 114 RBIs. Still, McCosky excited Athletics fans with his torrid .328 mark, ranking him second only to Williams. He hit just one home run, but he connected for 22 doubles and seven triples, and he scored 77 runs while driving home 52, all from the second slot in the order. In the league’s MVP balloting by sportswriters, however, DiMaggio won with 202 votes, Williams narrowly missed the honor with 201 votes and Kell came fifth with 132 votes. McCosky and Joost of the A’s received 35 votes each. Indeed, Barney enjoyed one of his three best years at the plate in 1947.

McCosky, despite a major injury, still mirrored his ’47 season in 1948 when Cleveland won the AL pennant and Philadelphia made a good run at the flag, finishing fourth with an 84-70 record, six games above the fifth-place Tigers (78-76). Batting .326, but with no home runs, Barney rapped 168 hits, (compared with 179 in 1947), slugged 21 doubles and five triples (compared with 22 and 7, respectively), scored 95 runs (he scored 77 times in 1947), walked 68 times (11 more than 1947), and struck out 22 times (seven less than 1947). Williams won the hitting crown again in 1948, averaging .369. McCosky’ average ranked below only that of Williams, Cleveland’s Lou Boudreau at .355, Dale Mitchell of the Indians at .336, and Al Zarilla of the Browns at .329.

On June 15, 1948, during the Tigers’ first night game at Briggs Stadium, McCosky was injured when, backpedaling for a high home-run ball hit by Dick Wakefield, the left fielder hit the concrete wall and fell awkwardly on the wooden frame holding the tarpaulin, twisting his back in the process. Reflecting on the incident in 1991, McCosky, who had a plug of tobacco in his cheek, recalled asking Sam Chapman, the first player on the scene, to pull out the chew. Chapman did, McCosky passed out, and he was carried from the field on a stretcher. Still, baseball being a highly competitive business, Barney said the injury was not serious, and he felt good enough to play within a week. On June 24, showing few ill effects, he went 2-for-4 and helped the A’s defeat the Browns, 6-5. In the eighth inning, the smooth-swinging flychaser ripped a two-run double and Ferris Fain hit a two-run triple for the game’s margin. Remarkably, McCosky was hitting .265 (44-for-166) at the time of his injury, but went on a tear, hitting a torrid .355. In the end, his final mark of .326 mark ranked fifth in the AL.

Jane McCosky, speaking in 1996, explained what happened in the following year, 1949: “The first day of the ’49 spring-training season, Barn bent down to pick up a ball and that was all it took – the pain was so severe, he was unable to play a single game the entire year. When we got back to Philadelphia, he spent weeks in traction and then underwent therapy. Finally in August, Mr. Mack placed him on leave for the rest of the year, and we returned to Michigan. In December, after exploratory surgery at Henry Ford Hospital, it was determined he had a pinched nerve in the last vertebrae. The doctors concluded that a fusion [of the lower three vertebra] was necessary. I credit his extraordinary team of surgeons with his successful recovery, since this type of operation was dangerous and rare at that time.

“Barney arrived at spring training in 1950 with a removable body cast, but soon dispensed with its use since, he complained, he had no mobility (just what the doctor wanted). At the opening game in Washington, he stretched his base hit into a double, sliding in and laying very still at second base, listening to his back clicking away as the adhesions from his surgery broke loose. That evening he received a telegram from his doctor in Detroit wanting to know, ‘What the hell are you doing in there?’ When the A’s arrived in Detroit, he underwent a thorough exam, and although he was OK’d for play, his back never responded with the flexibility he was used to. Because of this, his career was ended too soon.”

Having lived his baseball dream so successfully for seven seasons, McCosky hated letting it go. As it happened, his back made it so he could not play a full season as a regular again. For the Athletics in 1950, he played in 66 games, including 22 in the outfield, but the onetime speedster compiled his worst average to date, .240, including 5-for-25 as a pinch-hitter. Barney began the 1951 season with Philadelphia, hitting .296 in 12 games, but he was sold to Cincinnati, where he averaged .320 in 25 games. Cleveland, with former Tiger Hank Greenberg as GM, acquired McCosky, 33, to serve as a left-handed pinch-hitter late in the ’51 season, but Barney averaged only .213 in 31 games. Returning to Cleveland in 1951, McCosky played in 34 games in the outfield and hit a respectable .268, but he was 7-for-32 off the bench, a .219 mark. In 1952, he played in 80 games for Cleveland, averaging .213, but he batted .300 as a pinch-hitter, going 9-for-30. In 1953, McCosky got into 22 games, all as a pinch-batter, but he averaged just .190. The Indians finally released him on July 10. Greenberg offered his former teammate a coaching job in the minors, but McCosky went to work in Detroit.

McCosky was one of the top outfielders in the league before missing 1949 with spinal surgery, and the fact that he could overcome that injury and play four more seasons was remarkable. Compared to active ten-year veterans in 1953, when he retired, Barney’s average of .312 left him tied with Johnny Mize (inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1981) and trailed only Ted Williams (HOF, 1966, .344) and Stan Musial (HOF, 1969, .331). In addition, McCosky’s record, except for home runs and RBIs, rivals that of the greatest center fielder of the decade, Hall of Famer Joe DiMaggio. McCosky played six years of the 1940s but missed 1949 due to injuries, DiMaggio played seven years, including 1949, when he missed half of the season with a heel injury, and both lost the same three years from their prime due to the war.

McCosky was inducted into the Michigan Sports Hall of Fame in 1995, and as late as 2001, his .312 lifetime average ranked tenth best among Tigers with at least 2,000 career at-bats, and 81st in major-league history for players with a minimum of 1,000 games. A talented all-around athlete with a positive demeanor who was liked and respected by teammates and fans, the Detroiter represented the kind of ballplayer whom fathers, sons, and fans of all ages liked to root for at major-league ballparks like Briggs Stadium and Shibe Park. In addition to enjoying six .300-plus seasons, he was able to live the ballplayer’s dream of playing in a World Series, and even though Detroit lost in 1940, the hometown hero gave the game his very best, batting .304. In retrospect, Barney McCosky remains one of the great players ever to wear the Tiger uniform.

A version of this biography appeared in “Van Lingle Mungo: The Man, The Song, The Players” (SABR, 2014), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Last revised: May 15, 2022 (zp)

Sources

This essay about Barney McCosky’s major-league career is based partly on my McCosky article published in Oldtyme Baseball News in 1996. I used statistics from The Baseball Encyclopedia (Macmillan, ninth edition, 1993), Total Baseball (Sport Media Publishing, eighth edition, 2004), and Baseball-Reference.com. I also used clippings from the McCosky File in the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s Library in Cooperstown, New York, and articles covering the years 1939 through 1953 from the ProQuest Newspaper Database, accessed online from the Carnegie-Stout Public Library in Dubuque, Iowa. Further, I used material from an interview in with Barney McCosky by SABR member Norman Macht, and from my interview in 1996 with Jane McCosky, Barney’s wife, who also sent me statements about their marriage in 1946 and about her husband’s back injury in 1948, surgery in 1949, and the aftermath. In addition, I consulted several books, including William B. Mead, Baseball Goes to War (Washington, DC: Farragut Publishing, 1985); Mark Pattison and David Raglin, Detroit Tigers: List and More (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2002); and David M. Jordan, The Philadelphia Athletics: Connie Mack’s White Elephants, 1901-1954 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 1999).

Full Name

William Barney McCosky

Born

April 11, 1917 at Coal Run, PA (USA)

Died

September 6, 1996 at Venice, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.