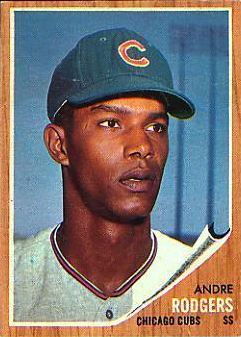

André Rodgers

In 1957, cricket star turned baseball player André Rodgers became the first major leaguer from the Bahamas after Negro Leaguer Ormond Sampson. By the end of the 2022 season, seven other Bahamians had followed him, although there was a gap from May 1983 to September 2011. Rodgers had by far the most extensive big-league career of his countrymen.1 He appeared in 854 games from 1957 to 1967, compiling a batting average of .249, 45 homers, and 245 RBIs. His primary position was shortstop. For three years (1962-1964), he was the regular at short for the Chicago Cubs, taking over for Ernie Banks when the slugger was moved to first.

In 1957, cricket star turned baseball player André Rodgers became the first major leaguer from the Bahamas after Negro Leaguer Ormond Sampson. By the end of the 2022 season, seven other Bahamians had followed him, although there was a gap from May 1983 to September 2011. Rodgers had by far the most extensive big-league career of his countrymen.1 He appeared in 854 games from 1957 to 1967, compiling a batting average of .249, 45 homers, and 245 RBIs. His primary position was shortstop. For three years (1962-1964), he was the regular at short for the Chicago Cubs, taking over for Ernie Banks when the slugger was moved to first.

Rodgers was a rangy, graceful athlete at 6’3” and 190 pounds. In 1956 old-timer Hans Lobert said, “He reminds me more of Marty Marion than any player I ever saw.”2 A year later, “Old Reliable” Tommy Henrich seconded this comparison, noting that Rodgers could go deep into the hole and make plays with his strong arm.3 In his earliest pro days, André’s nemesis was the curveball – the weapon he had never seen made him jump out of the batter’s box. Thus he sometimes took fastballs in order to practice hitting breaking stuff.4

Occasional flurries of errors also caused him to become discouraged and the inevitable batting slump would follow. He never quite put it all together at the top level. His fellow San Francisco Giants shortstop Ed Bressoud said, “André had extremely good power – I’m sure that’s what [owner] Horace [Stoneham] was counting on – he had a wonderful throwing arm and he ran quite well. André’s failing was his inability to catch the ball.”5

Nonetheless, Rodgers left a notable legacy. His career fueled a surge of popularity for baseball in his homeland, inspiring a generation of youths. Many of them made it to the minors, especially in the 1960s and 1970s, when – as longtime local sportswriters Fred Sturrup and Oswald Brown have attested – baseball became the most popular sport in the Bahamas. In particular, he had a profound influence on the third Bahamian big-leaguer, Ed Armbrister. After Rodgers died in December 2004, Armbrister said, “I followed André for a long time, and it was him who inspired me to become a professional ballplayer. André was always a positive guy. He was a strong-minded person, and I always said if I could just be like André I would be successful.”6

Kenneth André Ian Rodgers was born on December 2, 1934, in Nassau, the capital of the Bahamas. He was the eldest of seven children born to Arnold Percival Rodgers, a modestly paid civil servant,7 and Carmencita Theresa Baillou. His mother began calling the lad by his first middle name when he was young. According to his daughter Gina, he was finicky about using the accent over the ‘e’.

André’s four brothers were named Roy, Adrian, Lionel, and Randy; his two sisters were Leonora and Wendy. After André blazed the trail, his brothers pursued baseball careers too. Three of them – Adrian, Lionel, and Randy – made it to the minors. Roy was in spring training with the Giants in 1967 but was cut on the last day due to a reoccurring injury that would not heal, so he did not play pro ball.8 Of the four, Lionel might have had the best shot at joining André in The Show. Tragically, he was killed in an auto accident in January 1961 while at home in Nassau for the Christmas holidays.9 He had hit .345 to lead the Winter Instructional League in Arizona.

André’s best friend in life was Tony Curry, the second big-leaguer from the Bahamas, who was three years younger. Their families lived just around the corner from each other in Nassau. As children, young Tony and André awoke each other every morning and started the day with a swim in the ocean before going to church, which they attended daily. They and their brothers were also choirboys at St Mary’s the Virgin Church.

The amazing thing about Rodgers was that until 1952, he had never even seen a baseball. In fact, he had played baseball only once or twice before his big-league tryout. The sport was just starting to become visible in the British colony then, thanks to U.S. Navy sailors coming ashore. Other influences were at work too, as Arnold Rodgers said in 1957. “André’s baseball interest – like that of a lot of other Bahamians – really got started when Jackie Robinson started playing for the Dodgers and this interest was helped by an uncle, Thomas Lunn, who’s now 73 but still interested in the game. He taught me a lot about sports and explained the game to André. Uncle Tom had been to America for a number of years and learned quite a bit about baseball.”10

From the time he was a very small boy, Rodgers was interested in bats and balls. Yet, as one might imagine, cricket reigned then in the Bahamas. “When André was six, he started getting interested in cricket seriously,” said his father, who also had a reputation as a Bahamian cricket star. “He played junior cricket when he was 10. . .he developed into one of the best bowlers. . .he was also a good batsman.”11 André starred in cricket at his high school, St. John’s College. He also stood out in softball and played basketball and soccer, too.

“André might have gone to the Dodgers,” said Arnold Rodgers. “At one time, he wrote them for a tryout but all they did was send back a questionnaire and he was a bit discouraged.”12 However, another letter then changed the young man’s life.

In June 1953, Harry Joynes, a Canadian educator living in Nassau, wrote to John Schwarz, secretary of the New York Giants’ farm system. Joynes had seen Rodgers play cricket and softball, and recommended that the Giants give him a tryout. Schwarz replied that the Giants did not have a scout in the Bahamas. Rodgers could attend the Giants’ camp in Melbourne, Florida, for a tryout, but he would have to pay for his own travel and expenses. In a follow-up letter to Rodgers in January 1954, Schwarz sweetened the pot just a little, inviting him to Melbourne and offering to reimburse him for his expenses if he was signed. Joynes had also recommended another Bahamian, Texas Lunn (who could have been a cousin of André’s), for a trial. Schwarz advised André to have Lunn come along.

Under U.S. immigration laws, any player imported by a major league team had to have a contract. Since André was coming on a “make good” basis, he was told to inform the Customs people that he was coming for a visit. As he left the Bahamas, he told an official that he was coming to try out for a baseball team. In Miami, he told the immigration officer that he was just visiting. The discrepancy raised concerns, and he was deported within an hour.

Lunn, who had accompanied Rodgers, was allowed in and proceeded to Melbourne. He had an unsuccessful tryout, but insisted that the Giants give his friend a chance. Schwarz conferred with Alex Pómpez, former owner of the Negro Leagues’ New York Cubans and a Giants scout. Pómpez recommended that they bring Rodgers in as a contract player and processed the papers through the New York Customs office. André finally arrived at the Giants’ camp in Melbourne early in the spring of ’54.

When Rodgers stepped off the crowded bus in Melbourne, a Giant official greeted him by name. Somewhat surprised, the young Bahamian asked, “How did you know it was me?” The official replied, “You just look like a ballplayer.”

Former Giants pitching great Carl Hubbell directed the minor-league camp in Melbourne. When Rodgers informed him that he was a cricket player and had almost no experience with baseball, Hubbell thought that someone was pulling his leg.13 But experienced or not, André immediately began to draw attention. He was quick for his size and a quick learner. He stayed at the camp for a month, working three extra hours a day to learn the basics (as well as the rules of the game). Since he had played shortstop in softball, the Giants started him there. Scouts and managers, recognizing his potential and knowing that he would have no chance to improve if he went back to Nassau, volunteered to work with André. By the end of the month, three of the Giants’ Class D managers wanted him.14 His initial assignment was to Olean, New York, where he hit .286 with 9 homers and 85 RBIs in 125 games.

André’s next stop was St. Cloud, Minnesota, in the Class C Northern League. From the St. Regis Hotel in Winnipeg, he wrote to Harry Joynes early during the ’55 season, telling him he had collected 15 hits in his first 29 times at bat and closing:

“In the dinners they gave us in St. Cloud, they introduced the ballplayers to the folks on the committee, and gave them a little of their background. Charlie Fox [St. Cloud’s manager] told them that he shouldn’t be saying this, but I am going to take [Alvin] Dark’s place in three years’ time. He told me if I have a good year with him, I may go to AA or AAA next season, and I only pray I do. I am just as sure of you and the Mrs. pulling for me, as I am sure of myself. Mr. Joynes, the only trouble I can find with myself, and that is I always get down on myself, and when I do, in comes the slump, but I am going to try even harder this season. In that banquet they also mentioned your name, and Fox said that was one of the most wonderful things to happen to the Giants, in many a year, thanks to you, and I will do my best not to let you down.”

In only his second year of baseball, Rodgers won the Northern League’s 1955 batting crown with a .387 average. He also had 28 home runs and 111 RBIs, was voted to the All-Star team, and was selected as the league MVP. During the winter of 1955-56, he went to play for the first time with the Escogido Leones in the Dominican League. The Giants had ties there thanks to Alex Pómpez and Horacio “Rabbit” Martínez. In 1956, Escogido club president Paco Martínez Alba, the brother-in-law of Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo, formed a working agreement with New York.

Rodgers’ next season was with the Dallas Eagles in the AA Texas League. He hit 22 home runs, collected 90 RBIs, and hit .266, despite suffering broken facial bones from a pitched ball in a July game against Shreveport. Again he was named to the league All-Star team. Dallas Morning News sportswriter Merle Heryford described him as “graceful, deceptively fast and possessing the strongest infield arm in the circuit.”15 That winter he returned to Escogido.

By the spring of 1957, André was locked in a battle with Daryl Spencer for the Giants’ starting shortstop job. He made great copy for writers, including Jimmy Breslin, who was then with the NEA Feature Service. As Breslin related, Garry Schumacher, Giants promotional director and assistant to president Horace Stoneham, was excited about the prospect. Yet he was reluctant to beat the drum too loudly, given New York’s experience not so many years before with highly touted flop Clint Hartung.16

Rodgers had an outstanding spring, batting .292 and hitting five home runs. Paul Richards of the Orioles offered the Giants $100,000 for him, and baseball writers also picked him as the likely NL Rookie of the Year for the coming season.17 On April 1, the Giants announced that André had made the major league roster and would be their starting shortstop.

On April 3, 1957, Arthur Daley of the New York Times wrote, “When the Giants launch the National League season April 16 at Pittsburgh, their starting shortstop will be André Rodgers, a long-legged, smooth-swinging, hard-throwing lad of 22. There have been others who were as long of limb and as smooth of stroke and who gunned a baseball across the diamond as Rodgers guns ’em, but none could match André’s jet-propelled jump to the majors. Until 1952 the young man from the Bahamas never had seen a baseball. Until 1953, he never had held a baseball and until 1954 he never had played in an organized baseball game. Yet Rodgers, two weeks hence, will be wearing the traveling gray of the Giants at Forbes Field, entrusted with one of the most important positions on the club.”18

On April 16, 1957, the Giants took the field for their opener against the Pittsburgh Pirates. In an interview years later for a Bahamian publication, Rodgers recalled “the butterflies in my stomach and how I couldn’t get my legs to keep still” as he stepped into the batter’s box for the first time in the majors.19 He grounded into a 6-4 force play against Bob Friend in the top of the second inning, but in the sixth he singled to left off Friend for his first hit in the majors.

Not only did the first Bahamian in the majors play that day, the first man from the Virgin Islands made his debut too. Catcher Valmy Thomas, who’d also come out of nowhere in spring training to win a job with the Giants, entered the game in the sixth inning. During their first two years in the majors, the Caribbeans were roommates (one can imagine their lilting West Indian conversations). In 1999, Valmy remembered that André “loved the bright lights of the city” and that he was a good low-ball hitter thanks to cricket.20

Four days later, at the Polo Grounds, the rookie hit his first big-league homer, a solo shot off Harvey Haddix of Philadelphia. After a July 4 doubleheader, however, the Giants sent him down to Triple-A Minneapolis. The Sporting News wrote, “Lack of experience by the West Indian springtime phenom, and an apparent increasing loss of confidence, caused André to be shipped to the Millers in exchange for [Ed] Bressoud.”21

On February 6, 1958, Rodgers married Eunice Bethel. He made the big club, which had moved to San Francisco, but appeared in just six games before being demoted again, to Phoenix. That was in May, just ahead of the deadline to cut rosters down to the 25-man limit. He proceeded to beat out Vada Pinson for the Pacific Coast League batting title, .354 to .343. He also led the PCL in total bases and doubles while belting 31 homers – the old Phoenix Municipal Stadium was a bandbox22 – and driving in 88. He rejoined the Giants in September, but was still regarded as “easy prey for major league pitching.”23

In 1958-59, Rodgers played again with Escogido. The entire Leones lineup was made up of present or future big-leaguers, the most notable being Bill White, Felipe Alou, and Manny Mota (Mota was still a Giants farmhand). The playoff finals against arch-rival Licey featured a notorious incident: After a brushback scuffle, Generalissimo Rafael Trujillo’s brother Petán came out of the stands with armed guards and slapped Rodgers in the face.

When the 1959 season opened, Rodgers was back with the Giants. On May 17 at Seals Stadium, he enjoyed his only two-homer game in the majors, hitting solo shots off Bob Purkey and Tom Acker of the Reds in a 9-1 laugher. Another memorable moment from that season – though it was not a positive one – came on June 30 at the Los Angeles Coliseum. Giants pitcher Sam Jones was in top form and had a no-hitter through 7 2/3 innings. Jim Gilliam of the Dodgers hit a chopper over the mound, but shortstop Rodgers couldn’t find the handle. Yet scorer Charlie Park from the Los Angeles Mirror scored it a base hit, insisting that Gilliam would have beaten it out. Park was alone in his view; his fellow writers were incredulous, Rodgers thought he bobbled it enough to be called an error, and even the LA fans howled. Sad Sam Jones felt robbed.24

That year Rodgers stuck through late July, but he endured yet another demotion to Phoenix, as the Giants called up both Willie McCovey and José Pagán. Once more André was recalled in September, but he got into just two more games. In 1960, though, he finally stayed with the Giants for the full season. He appeared in 81 games, as manager Bill Rigney also used him at third base, first base, and even a couple of times in left field.

After the season, Rodgers joined the Giants as they toured Japan. While he was over there, on October 31, San Francisco traded him to the Milwaukee for Alvin Dark.25 In March 1961, André said, “I was rather surprised when I was traded. I guess I should have expected it. I didn’t play much with the Giants and the fans in San Francisco gave me a pretty good going over when I did play. My first impression was that it would be good for me to get away from San Francisco.” He went on to observe that the Braves had obtained Roy McMillan, a superb-fielding shortstop, and had Eddie Mathews at third. Thus, the best he could hope for was a utility role. “I’m resigned to it, but I’d like to get another chance to play regularly,” he concluded. “I think I can do it now. This is my fifth year in the majors.”26

Rodgers didn’t get his wish for another year, but a few days later, he got the change of scenery that would eventually make it happen. He went to the Cubs along with Daryl Robertson for Moe Drabowsky and Seth Morehead. Milwaukee manager Charlie Dressen unkindly observed that the Braves gave up “practically nothing” in the trade.27 As it turned out, the Braves got little value from either Drabowsky (who went on to success in Baltimore) or Morehead. On the contrary, the Cubs got the best part of Rodgers’ career.

In 1961 André played mostly first base behind Ed Bouchee, also backing up Ernie Banks and Jerry Kindall at short. During spring training 1962, the Chicago Sun called him “a perennial on-the-brinker.”28 The breakthrough came, though, as he finally claimed a regular shortstop job and posted his highest average as a big-leaguer, .278 in 461 at-bats. He slumped to .229 the next year, and though he hit just .239 in 1964, he connected for 12 homers and 46 RBIs, both career highs.

Those were dreary years for the Cubs, who finished deep in the second division under the “College of Coaches” in 1961 and 1962. Yet Rodgers benefited from the faith that Charlie Metro, one of the head coaches – who remembered his performance in the PCL – showed in him. After much turnover at shortstop in early 1962, “Metro decided the only man who had the potential to handle the position was Rodgers. He put André back at short and…stress[ed] all the good things he was doing. ‘It wasn’t easy,’ said Metro, ‘because his confidence was shaken, not only by the booing of the fans but also countless vicious letters he got when he was going bad.’”29

Things were somewhat better for the team during Rodgers’ remaining two seasons in Chicago, at least in terms of winning percentage. Bob Kennedy, who took over as sole manager in 1963, also liked André. It’s true that the shortstop’s hitting was up and down, and various observers cast aspersions on his defense, but his fielding percentage was just a shade below the league average and his range factor was above average. After second baseman Ken Hubbs died in an airplane crash in February 1964, Kennedy said, “He and André Rodgers developed into one of the best keystone combinations in the league [in 1963].”30

Still, there was no fanfare when Rodgers left Chicago. On December 9, 1964, the Cubs traded him to the Pittsburgh Pirates for cash and Roberto Pena, a minor leaguer. At the time of the trade, Pittsburgh general manager Joe L. Brown said that Rodgers would compete with Dick Schofield Sr. for the shortstop job.31 Jimmy Stewart was the heir apparent in Chicago, but as it turned out, Pena backed up 22-year-old Don Kessinger in Chicago. André and Schofield were in reserve behind another good-fielding young shortstop, Gene Alley.

In April 1965 Les Biederman of the Pittsburgh Press wrote a feature about Rodgers, observing that he still had “the trace of a clipped British accent.” The most intriguing part of that story, though, was the comment from the Pirates’ old Hall of Fame star, Pie Traynor. Traynor said, “He might have been a great one if he had the advantage of being brought up on baseball as most American boys are. But he never had the benefit of learning the game early as a youngster. Yet he has all the grace and actions of a man who knows what it’s all about.”32

Rodgers still saw a good bit of action in 1965 (178 at-bats in 75 games), as manager Harry Walker liked his ability to play all four infield positions. However, his playing time fell off markedly after that. He came to the plate just 59 times in 36 games during 1966, when he missed six weeks in June and July with a torn rib muscle. In 1967, it was 70 plate appearances in 47 games. He served largely as a pinch-hitter and utilityman, as Gene Alley seldom missed a game.

Rodgers, who operated his own sporting goods store in Nassau in the off-season, played his last game in the majors on September 30, 1967. After that season, the Pirates put him on the roster of their top farm club, Columbus. He was invited to spring training camp in 1968, but accepted his demotion to the minors for the first time that decade. He got into 43 games for the Jets, playing largely at first base. However, he spent much of the year on the disabled list.

In 1969, Rodgers then found a new opportunity – in Japan. “André had a yen to stay in US ball,” wrote Jack O’Brian in the Lebanon (Pennsylvania) Daily News, “but Tokyo offered more dollars.”33 In 49 games with Yokohama’s Taiyo Whales, he hit .just 210 with 4 homers and 12 RBIs.

Rodgers then returned to the Bahamas. “When he returned home,” his nephew Terran Rodgers said in 2011, “he ran Rodgers Sports Shop for several years, then moved fully into the retired mode and began living on his major-league pension.” He played with his brothers for local teams called Murray Kelly, Big Q, and Paradise Island. He also managed the 1971 national team that appeared in the National Baseball Congress tournament in Wichita, Kansas. He played in the local softball league for Taylors Industry from 1971 to 1973 and managed the team from 1974 to 1977.

André and Eunice had three children from 1958 to 1963: Gina, Kenneth André Ian Jr. (whose godfather was Tony Curry), and Ramon. The couple parted ways, and Rodgers had another daughter named Debra (born 1974) from a different union.

Rodgers received recognition at home as a sporting hero during his lifetime. In 1989 he became part of the inaugural group of 14 athletes named to the National Sports Hall of Fame in the Bahamas (the next group was not inducted until 2003). That June, the baseball diamond at the Queen Elizabeth Sports Centre was renamed in honor of him.

On three separate occasions during 2004, Rodgers was admitted to Princess Margaret Hospital suffering from severe respiratory problems. He was a quiet and uncomplaining man, though, and the extent of his illness was generally unknown. It was known that he had a rare disease that caused poor circulation of blood in his right leg. As a result, that leg was amputated on his last visit to the hospital in late November.34 Shortly thereafter, local columnist Oswald Brown, a big baseball fan, issued an editorial about Rodgers’ impact in baseball and beyond.

“Aside from the national pride that this generated not only among baseball fans but Bahamians in general, what this meant to The Bahamas as a country could not be measured in dollars and cents. Every time André Rodgers stepped on the field in baseball stadiums across the United States and his name and where he was from was announced, that represented thousands and thousands of dollars of free publicity for The Bahamas. Given the fact that the late 1950s was when the strategy was shifted from marketing The Bahamas as a playground for the rich and famous to promoting it as a popular tourist destination, it can easily be concluded that André Rodgers was one of the country’s greatest assets at the time.”35

Just a few weeks later, on December 13 – not long past his 70th birthday – Rodgers died at home. In its editorial the next day, the Freeport News wrote, “The Bahamas lost not only a truly great gentleman but arguably the most important sports icon in this country’s history.”36

The little ballpark bearing Rodgers’ name was demolished in 2006. Ostensibly, the new $30 million multi-sport facility that eventually arose in its place was to keep his name,37 but it honored Olympic sprinter Tommy Robinson instead. The loss of André Rodgers Stadium dealt the coup de grâce to the already moribund Bahamas Baseball Association.38 However, the Bahamas Baseball Federation, which has helped revive the sport in the islands in recent years, had launched the André Rodgers Baseball Championships in 2003, drawing teams from around the islands.

A 61-minute documentary called Gentle Giant: The André Rodgers Story was released in 2014. The producer and director was his daughter, Gina Rodgers-Sealy, who noted with pride that it won a San Francisco Film Award and was an official selection at 12 different film festivals.

The 20th edition of the André Rodgers Baseball Championships was held in June 2022, continuing to honor the foremost Bahamian baseball player. Meanwhile, prospects from the islands are still making it into the pros. One of them, Lucius Fox, just happens to be a tall, rangy shortstop who was originally signed by the Giants. Fox reached the majors with the Washington Nationals in 2022; he was preceded by Jazz Chisholm in 2020.

In July 2016, the Bahamian government announced the construction of a new André Rodgers National Baseball Stadium. Rodgers’ nephew Terran, an architect by profession, was the project manager. Prime Minister Perry Christie said, “Build a stadium that would leave me in awe as I drive by it, something that would say this is a national baseball stadium.”39

The complex was originally scheduled to open in 2018. At long last, the opening ceremony took place on December 4, 2022. Fittingly, Team Bahamas won the first game held there, defeating the U.S. Virgin Islands in Caribbean Cup competition. It was two days after what would have been the 88th birtday of André Rodgers.

Last updated: December 5, 2022

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Craig Kemp, president of the Bahamas Baseball Federation, for his help in reconnecting the authors with the Rodgers family — and to Gina Rodgers-Sealy for additional updates.

Sources

This biography is adapted from “André Rodgers” by Lyle K. Wilson, Esq., originally published in the 1999 edition of the SABR annual The Baseball Research Journal.

As Lyle wrote in 1999, “Harry Joynes, who first wrote to the Giants about André, kept the letters from the Giants and clippings of André’s career. Shortly before his death, Joynes mailed a box full of materials to André’s brother, Randy. The author spent an afternoon with André, Randy, and Randy’s son, Terran, in June of ’98. Terran had graciously arranged the meeting and made arrangements for me to obtain about 80 pages of copies from ‘the box.’ The devotion of a friend preserved this history so that we can now enjoy it. Thank you, Mr. Joynes, and thanks to André, Randy, and Terran.”

In 2011, Terran Rodgers wrote, “I remember meeting with Mr. Wilson and sitting with him as he interviewed Uncle André. It was a very good time.”

www.baseball-reference.com

www.retrosheet.org

www.japanbaseballdaily.com (Japanese statistics)

Family tree online (http://familytreemaker.genealogy.com/users/b/e/t/Andre-O-Bethel/WEBSITE-0001/UHP-0404.html)

Sporting News Baseball Register, 1965

Notes

1 The other Bahamians who had played in the majors as of 2018: Tony Curry (1960-61; 66); Wenty Ford (1973); Ed Armbrister (1973-77); Wil Culmer (1983); Antoan Richardson (2011, 2014).

2 Rives, Bill. “Bahamas’ Softballer Nifty Dallas Prospect.” The Sporting News, March 28, 1956: 27.

3 “Cautious Henrich Can See Great Career for Rodgers.” The Sporting News, March 27, 1957: 10.

4 Maule, Tex. “Crack Shortstop Andre of Eagles Started in Cricket.” The Sporting News, August 8, 1956: 31.

5 Bitker, Steve. The Original San Francisco Giants: The Giants of ’58. Champaign, Illinois,: Sports Publishing LLC: 2004: 151.

6 Longley, Sheldon. “Rodgers gets a sporting salute!” Nassau Guardian, December 21, 2004.

7 McLemore, Morris. “Andre Rogers [sic], Bahamian.” The Miami News, April 25, 1957: 1D.

8 E-mail from Terran Rodgers to Rory Costello, November 15, 2011.

9 “Rodgers’ Brother Killed in Crash.” Associated Press, January 12, 1961.

10 McLemore, op. cit.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 King, Joe. “Giants See Chance for Help from Pair of Big Rookies.” The Sporting News, March 13, 1957: 11.

14 Ibid.

15 Heryford, Merle. “Rodgers, Demeter Top Peach Crop.” Undated 1956 clipping from Harry Joynes collection.

16 Breslin, Jimmy. “Hartung Keeps New York From Getting Too High On Rodgers.” NEA Feature Service, April 10, 1957.

17 Reichler, Joe. “Tony Kubek, André Rodgers Choice For Rookie-Of-Year.” Associated Press, March 22, 1957.

18 Daley, Arthur. “Giant-Step Taker; André Rodgers.” New York Times, April 3, 1957.

19 Knowles, Marjorie. “Andre Comes Home.” Undated clipping, possibly from a Bahamian newspaper insert, from Harry Joynes collection.

20 In-person interview, Rory Costello with Valmy Thomas.

21 King, Joe. “Phenom Rodgers Fades, Bressoud Back With Giants.” The Sporting News, July 17, 1957: 11.

22 “Phoenicians Set Records.” The Arizona Republic, August 13, 1969.

23 McDonald, Jack. “Only 2 Spots Open in Giant Regular Cast.” The Sporting News, February 25, 1959: 17.

24 “Sad Sam Jones Is Even Sadder After Scorer Spoils No-Hitter.” Associated Press, July 2, 1959.

25 A noteworthy aspect of the deal was that the Giants obtained Dark to be their manager, giving him a two-year contract. Dark said he would not go to training camp as an active player but hadn’t decided whether he might later become a playing manager (1960 was in fact his last season as a player).

26 “Rodgers Wants Steady Job.” Associated Press, March 28, 1961.

27 “Braves Deal For Hurlers.” Associated Press, April 1, 1961.

28 “Ernie Banks Now on First.” Chicago Sun, March 6, 1962: S22.

29 Munzel, Edgar. “Former Butterfiners, Rodgers Shaping Up as Defensive Demon.” The Sporting News, July 14, 1962: 22.

30 Kennedy, Bob. “Loss of Hubbs Changes Cubs’ Outlook.” Associated Press, February 18, 1964.

31 “Bucs Give Cash, Pena For Rodgers.” United Press International, December 10, 1964.

32 Biederman, Lester J. “Baseball Came Hard To André Rodgers – It Wasn’t Cricket.” Pittsburgh Press, April 18, 1965: Sec. 4-3.

33 Lebanon Daily News, April 10, 1969.

34 Longley, Sheldon. “The death of a Bahamian legend – André Rodgers’ death shocks community.” Nassau Guardian, December 14, 2004. Rodgers’ declining health may have been the reason that he declined requests to be interviewed for Steve Bitker’s book.

35 Brown, Oswald. “A genuine Bahamian hero.” Freeport News, November 26, 2004: 4.

36 “Remembering André Rodgers.” Freeport News, December 14, 2004.

37 “Andre Rodgers park to be demolished.” Freeport News, June 29, 2006.

38 Sturrup, Fred. “Sports Minister knocks demolition decision.” Freeport News, March 3, 2010.

39“Contract signed for $21 mil. Andre Rodgers National Baseball Stadium.” Nassau Guardian, July 20, 2016.

Full Name

Kenneth André Ian Rodgers

Born

December 2, 1934 at Nassau, New Providence (Bahamas)

Died

December 13, 2004 at Nassau, New Providence (Bahamas)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.