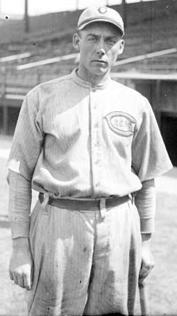

Edd Roush

Known as one of the feistiest players in baseball history, Edd Roush channeled that energy into a Hall of Fame career. An old-timer was quoted in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in 1919 saying that Roush was more like the fiery old Baltimore Orioles of the 1890’s than any other player in the National League. The observer stressed Roush’s versatility and his knack at doing the unexpected when it would help the most. John McGraw, in a similar vein, once said, “that Hoosier moves with the indifference of an alley cat.” Pat Moran claimed that “all that fellow has to do is wash his hands, adjust his cap and he’s in shape to hit. He’s the great individualist in the game.” Roush led his team, the Cincinnati Reds, to the World’s Championship in 1919.

Known as one of the feistiest players in baseball history, Edd Roush channeled that energy into a Hall of Fame career. An old-timer was quoted in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in 1919 saying that Roush was more like the fiery old Baltimore Orioles of the 1890’s than any other player in the National League. The observer stressed Roush’s versatility and his knack at doing the unexpected when it would help the most. John McGraw, in a similar vein, once said, “that Hoosier moves with the indifference of an alley cat.” Pat Moran claimed that “all that fellow has to do is wash his hands, adjust his cap and he’s in shape to hit. He’s the great individualist in the game.” Roush led his team, the Cincinnati Reds, to the World’s Championship in 1919.

A left-handed hitter with a lifetime average of .323 in 18 seasons, Edd Roush was the best place hitter in the National League toward the end of the Deadball Era, winning batting championships in 1917 and 1919 and finishing second in 1918. “Some batters, and good ones too, scoff at the whole theory of place hitting, calling it a myth,” he said. “They are wrong, however.”

Roush wielded a short, thick-handled bat that weighed 48 ounces, one of the heaviest ever in baseball. He snapped the bat at the ball with his arms and placed line drives to all parts of the field by shifting his feet after the ball left the pitchers hand and altering the timing of his swing. “Place hitting is in a sense glorified bunting,” he said. “I only take a half swing at the ball, and the weight of the bat rather than my swing is what drives it.”

On defense center fielder Roush combined excellent speed with an ability to turn his back on the baseball and run to the spot where it would drop to earth. Edd was considered by many to be the premier defensive outfielder of the National League during the Deadball era. He was often compared defensively with Hall of Famer Tris Speaker.

Edd J and his twin brother, Fred, were born on May 8, 1893, in the small southwestern Indiana town of Oakland City. They were sons of William C. Roush and Laura (Harrington) Roush. The J in Edd’s name was not an abbreviation but rather stood for both of his grandfather’s names, Joseph and Jerry. His father William was a good semipro baseball player who owned a dairy farm. Doing chores on the farm as a boy helped Edd develop strong hands and arms that allowed him to swing the heaviest bat in baseball.

He began his baseball career in 1909 with the semipro Oakland City Walkovers, getting a shot when one of the team’s regular outfielders failed to show up. “We waited for five minutes and the outfielder never did show, so they gave me a uniform and put me in right field,” Roush recalled. “Turned out I got a couple of hits that day and I became Oakland’s City’s regular right fielder for the rest of the season.” In 1911 he learned that some of the Walkovers were receiving $5 per game, and he wasn’t one of them. In the first of his many battles over money with team management, Edd jumped to a rival team from Princeton, 12 miles due west of Oakland City. “And don’t think that didn’t cause a ruckus,” he said more than half a century later. “I think there are still one or two around here that never have forgiven me to this very day.”

This was the first of his many battles over money with team management. Roush next entered the professional ranks, playing for Henderson, Kentucky in the Kitty league in August of 1911. He threw right handed and played second base in 10 games for Henderson. He soon switched back to his natural left handed style and moved to the outfield. Roush as a youth often threw right handed because there was no left handed glove available.

In 1912 Edd began playing with Princeton of the Ohio Valley league. He then moved on to the Evansville club of the Kitty league in late July of 1912, remaining there until early in the season of 1913. He batted .284 in his first year with Evansville and was hitting over .300 in August 1913 when Evansville sold him to the Chicago White Sox. Ironically the Sox signed him before Garry Herrmann, owner of the Reds who had been scouting him, could ink him to a deal. Herrmann later was to get his man.

Herrmann had been corresponding with Louis Heilbroner who often scouted prospects in the Midwest. Heilbroner had good reports on Roush and suggested Herrmann take up the matter with Harry W. Stahlhefer, President of the Evansville club. Herrmann did and learned that scouts Deacon McGuire of Detroit and “Sinister” Dick Kinsella of the Giants were looking Roush over as well. Both had asked for an option on Roush but Stahlhefer refused, stating he wasn’t yet ready for the majors because he was weak against left handed pitching and had a sore arm.

Herrmann appeared ready to make an offer for Roush’s contract when he learned Stahlhefer had already sold it to the White Sox for $3,000. Roush made his major league debut on August 20th, grounding out three times against the Boston Red Sox. He batted 10 times in about a month with Chicago, earning the first of his lifetime 2,376 hits off Chief Bender on September 11th before being farmed out to Lincoln of the Western League. His roommate was Ray Schalk, later an opponent in the notorious 1919 World Series.

Writers covering the Sox noticed Roush’s ability to throw with either arm. Ring Lardner, in the Chicago Tribune, wrote; “If Cal keeps Rousch [sic] in center the youngster will probably throw right handed one series and left handed the next.” Lardner also called him the ambidextrous Mr. Rousch. A Washington Post article said Roush carried two gloves, so that in left field he could throw right handed and in right field he could throw left handed. Roush himself said that although he could throw right handed the ball would not carry as far so he stuck with his natural left hand throw. It does not appear that Edd ever threw right handed in a major league game.

In 1914 Roush violated his reserved contract with the White Sox, signing with the new Federal league Indianapolis club. Not happy with his contract or his return to the minors, he had written Bill Phillips of Indianapolis to see if he needed an outfielder. Phillips answered with a telegram to come and talk contract. Playing part-time Roush showed his potential, hitting .325 in 166 at bats for the Federal League champions. An October 1914 story in The Sporting News claimed that at a field day in Indianapolis Roush had bunted and ran to first in 3 and 1/5 seconds to tie a record. In April of that year Edd married Essie May Swallow.

In 1915 the team moved to Newark, where Edd, inserted into the lineup regularly by player-manager and life-long friend Bill McKechnie, hit .298 with 28 stolen bases. Following to the demise of the Federal League after the season, John McGraw and the New York Giants were able to purchase Roush’s contract for 1916.

Edd hated New York, and he especially hated playing for the demanding John McGraw. “If you made a bad play he’d cuss you out, yell at you, call you all sorts of names,” he recalled. “That didn’t go with me.” Baseball Magazine in its July issue had stated that Roush should prove to be an outfielder of rare ability, some thinking he was the superior of Benny Kauff in the field. However it also stated that Roush had failed with the stick and been relegated to the bench.

Roush got off to a slow start and was hitting just .188 on July 20th, 1916, when the Giants sent him to the Reds in what later became known as the “Hall of Fame” trade — in exchange for Buck Herzog and Wade Killifer, McGraw shipped Christy Mathewson, McKechnie and Roush, all who were bound for Cooperstown, to the Cincinnati Reds.

“I still remember the trip the three of us made as we left the Giants and took the train to join the Reds,” Roush recalled. “McKechnie and I were sitting back on the observation car, talking about how happy we were to be traded. Matty came out and sat down and listened, but didn’t say anything. Finally I turned to him and said, ‘Well, Matty, aren’t you glad to be getting away from McGraw?’ ‘I’ll tell you something, Roush,’ he said. ‘You and Mac have only been on the Giants a couple of months. It’s just another ball club to you fellows. But I was with the team 16 years. That’s a mighty long time. But I appreciate McGraw making a place for me in baseball and getting me this managing job. He’s doing me a favor, and I thanked him for it. And by the way, the last thing he said to me was that if I put you in centerfield I’d have a great ballplayer. So starting tomorrow you’re my center fielder.’”

When Mathewson carried through on his promise, Roush found himself playing alongside Greasy Neale, who was also in his first year with the Reds but had been with the team since the start of the season. “The first game I played there, about three or four fly balls came out that could have been taken by either the center fielder or right fielder,” Edd recalled. “If I thought I should take it, I’d holler three times; ‘I got it, I got it, I got it.’ But Greasy never said a word. Sometimes he’d take it and sometimes he wouldn’t. But in either case he never said a thing. We went along that way for about three weeks. Finally, one day Greasy came over to and sat down beside me on the bench. ‘I want to end this, Roush,’ he says to me. ‘I guess you know I’ve been trying to run you down ever since you got here. I wanted that center-field job for myself, and I didn’t like it when Matty put you out there. But you can go get a ball better than I ever could. I want to shake hands and call it off. From now on, I’ll holler.’ And from then on Greasy and I got along just fine. Grew to be two of the best friends ever.”

Roush hit .287 with 14 triples in 69 games for the Reds in 1916. Edd’s twin brother Fred spent that season playing third base for Dawson Springs of the Kitty League. A Sporting Life article stated that Fred had been looked over by major league scouts. He never did reach the major leagues although he played a few seasons in the minors. The trade really began to pay off for Cincinnati the next year when Edd won the first of his two batting titles, beating out Rogers Hornsby, .341 to .327. Roush’s only child, Mary Evelyn, was born to Essie on August 18, 1917.

After hitting .333 and losing the batting championship by two percentage points to Zack Wheat in 1918, he earned his second batting title the next year by hitting .321, edging out Hornsby again by three points. Amazingly, although it was good enough to lead the league, Roush’s .321 was his lowest batting average over the 10-year period of 1917 through 1926.

Edd registered for the military draft in 1918 but was not chosen. Near the end of the season, as he was chasing his second straight batting title a tragedy occurred that took Edd away from the team. News reached Roush that his lineman father had been injured falling off a telephone pole. Edd rushed home to Oakland City where his father died from head injuries.

A January 1919 Sporting News story related that Edd lost the batting title because of a protested game. He was the culprit. As he came in from centerfield to make a catch he juggled and then held onto the ball. He then threw the ball into the infield to retire a runner whom the umpires ruled had not tagged up. The game was protested, and the protest was upheld, ruling that the runner could tag up and advance when the ball first made contact with Roush’s glove, not when the ball was finally secured. Roush had 2 hits in 3 at bats in the game, but the results were thrown out and the game replayed.

As was often the case, Edd held out before the 1919 season. He never liked spring training and felt he stayed in shape working the farm and hunting around Oakland City in the off season. New manager Pat Moran, who had taken over when Mathewson did not return from France and military service in time for the Reds to retain him, convinced Edd to sign a contract just before the season. Edd returned just in time to make the opening day lineup. Edd won the second of his batting titles that season, leading the Reds to their first National League pennant.

The 1919 World Series is forever tainted by the Black Sox Scandal. In 1920 word came out that eight members of the White Sox had thrown the series, purposely losing games after being paid by gamblers. Roush became vehement when questioned throughout his life about the series, consistently stating that the Reds were the better team. He was quoted as saying that after the first two games the Sox played it straight as the gamblers had not paid them off properly.

He also frequently related a story about Reds pitcher “Hod” Eller being approached by a gambler late before the eighth and final game of the series. Roush had heard a rumor about Reds players possibly being approached by gamblers. He brought this information to the attention of Reds manager Pat Moran. Moran and Roush first approached team captain Jake Daubert, who said he knew nothing about any Red being approached. Roush figured it would have to be a pitcher. They spoke to starting pitcher Eller who confirmed it had happened.

Eller said the man rode up in an elevator with him, getting off at the same floor. He offered Hod five $1000 bills to throw that day’s game. Eller related he told the man if he didn’t move on he would punch him in the nose. Moran stared Eller in the eye for a long time before saying he would allow him to pitch but at the first sign of anything funny he would be replaced. The Reds went on to take the game and series.

After the Series Edd returned home in his touring car and ladies of the M. E. Aid Society served a banquet in his honor. Over one hundred friends and boosters of Roush attended. R. Walter Geise acted as toastmaster. Claude Trusler, Roush’s first manager, spoke of the old Walk-Over team. A fine Winchester shotgun was purchased and presented to Roush.

Edd actually reported for spring training in 1920, such an unusual occurrence that The Sporting News commented on it. “It will be interesting to see how the training works on Edd Roush. That marvelous performer has always dodged the training trip and conditioned himself on his farm. This time he is going to the camp; if he hits way over his usual mark, he’ll swear that he made a huge mistake before, and if he falls down he’ll never go south again.” He was also ejected from a game that June when he sat down during an argument, put his head down, and fell asleep. When infielder Heinie Groh had trouble waking him the umpires ejected him for delay of game.

During the 1920-1921 off-seaons Edd was injured when his brother Fred accidentally plunked Edd with birdshot, one hit each to the lip, cheek and thumb. That December Baseball Magazine stated that Roush was the greatest outfielder in the National League: “In ground covering, he has no superiors and few approximate equals, while he was a fine a base runner as ever and hit for the grand average of .352.”

With the explosion of offense in the 1920s, Roush averaged .350 over a four year period, 1921-1924, but won no additional batting crowns. He did lead the NL with 41 doubles in 1923 and with 21 triples in 1924. In March 1924, Pat Moran passed away soon after reaching the Reds spring training camp. Jack Hendricks was chosen over Jake Daubert to be the new skipper. Roush made it be known that under no circumstances would he have wanted the job.

After the 1926 season the Giants reacquired Roush from the Reds in a trade for George Kelly and cash. Remembering the abuse he’d received from McGraw back in 1916, Edd tried to get New York to trade him by holding out for a salary of $30,000. “I’ve been trying to get you back ever since I traded you a long time ago,” said McGraw. “Now you’re either going to play for me or you’re not going to play at all.” Roush ended up signing a three-year contract worth a total of $70,000. The Sporting News, announcing the signing, said that farmer Roush, “who raises, among other things, the price of his services with each fiscal round-up, is ready to face the high cost of living in New York.” He twice hit over .300 for the Giants, but his legs had started to give out on him.

In July of 1928 Edd was sent to St. Louis for an operation at St. John’s hospital to repair torn stomach muscles. He sat out the entire 1930 season in another salary dispute, then returned to the Reds for one final season in 1931.

During his playing career, Roush was well known for two things other than his great playing ability: his numerous disputes over salary, and his distaste for the bean ball. Roush generally skipped spring training, using a holdout as the excuse to report just before the season began. He felt he stayed in good enough shape hunting in the off season and didn’t need the six weeks of spring training. In 1922 he held out all the way until July.

And indeed Roush had an intense dislike for pitchers throwing at him. As he often related he would take it out on the infielders, spiking them when given the opportunity. Soon the infielders would convince the pitchers not to throw at Roush. Many years after retiring Roush met up with an opponent and asked if the player remembered him. The player replied, “sure I do” and pulled up his pants leg and showed him a spike scar.

In an interview with Bill Koch of the Cincinnati Post in 1987, Roush told the story of a game against the Cubs in which a pitcher threw at him. Reaching first he was able to spike Charlie Grimm on the ankle. A conference on the mound ensued. Manager and second baseman Rogers Hornsby ended the discussion: “I’ve played against him for years and I played with him one year. You guys get back on the bench and quit throwing at this guy. He’ll take us all out of here!”

After retiring as a player Roush only held one job in baseball, serving one season as coach with the 1938 Reds under his best friend, Bill McKechnie. Roush’s comment on leaving the Reds was that they needed a good third baseman. The Reds went out and obtained Bill Werber and went to two straight World Series, winning in 1940.

Edd invested his hard-fought baseball salary wisely, and was able to retire after his playing days were over during a time when most players had to move on to another career. He built a house in Bradenton, Florida and for 35 years the Roushes maintained it as a winter residence. After rarely attending spring training as a player Edd frequented spring training ballparks as a retired elder statesman, regaling listeners with tales of the old days.

Edd devoted himself to his hometown of Oakland City, where he and and Essie raised daughter Mary. Mary went on to teach Physical Education at Manatee Junior College, Buckhannon College and West Virginian Wesleyan College. She married and had two daughters, Susan and Rebecca. Susan grew up to be Dr. Susan Dellinger, a SABR member. Edd’s beloved Essie passed away in 1978. In his later years Edd lived with his daughter Mary who often took him to meetings with former players. Edd survived long enough to nurture 3 great-grandchildren. After being surrounded by women in his home for so long, Edd was especially proud of his great-grandsons Jade, Greg and Matt.

Edd served on the town board and school board and ran the Montgomery cemetery for about 35 years, where he is now buried. He was also elected President of the Board of Directors of First Bank and Trust Company. As a sign of respect baseball fields were named for Edd in Oakland City and Bradenton.

Edd was named to the Indiana and Ohio Baseball Halls of Fame. In 1960 he was voted into the Cincinnati Reds Hall of Fame. He was inducted into baseball’s Hall of Fame on July 23, 1962, along with Jackie Robinson, Bob Feller, and his dear friend Bill McKechnie. In 1969, during baseball’s centennial celebration, Roush was voted the greatest Reds player in their history.

On March 21, 1988, Edd Roush left us the way all great ballplayers should: he passed away just prior to a spring training game at Bradenton’s Bill McKechnie Field. He was 94.

Note: An earlier version of this biography appeared in Tom Simon, ed., Deadball Stars of the National League (Washington, D.C.: Brassey’s, Inc., 2004).

Sources

Dr. Susan Dellinger, Edd’s granddaughter, SABR member and keeper of the Edd Roush flame.

Phone interview with Mary Roush Allen, 2 July 2001

Player file, National Baseball Library, Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York

Bat records by Hillerich and Bradsby (Louisville Sluggers)

www.deadballera.com

www.retrosheet.com

www.ancestry.com

Marion County, Indiana Marriage Records

Gibson County, Indiana Birth Records

1918 WWI Draft Registration Gibson County, Indiana

1930 US Federal census Oakland City, Gibson County, Indiana

Florida Death certificate

Jasper Herald (IN) 5 September 1988 column

Indianapolis Star Magazine 2 July 1974 interview with Roush by Rick Johnson

Chicago Tribune 1913-31

Cincinnati Times Star 1919

Cincinnati Enquirer 1916, 1919, 2000

Cincinnati Post 1987 19 May interview with Roush by Bill Koch

Obituaries New York Times, Cincinnati Enquirer 1988

Oakland City Journal 1918, 1919

Brooklyn Daily Eagle 1919

Indianapolis Star 1914

Washington Post 1913

New York Times 1928

New York American undated article by Damon Runyan

Los Angeles Times 21 March 1937

Reach Guides 1913-31

Spalding Guides 1913-31

New York Telegram 26 March 1931

Sporting Life 1913, 1915, 1916

The Sporting News 1913-31

Baseball Magazine 1916, 1917, 1918, 1921

Williams, Peter. When the Giants Were Giants. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: Algonquin Books, 1994.

Shatkin, Mike ed. The Ballplayers. New York: Arbor House William Morrow, 1990.

Full Name

Edd J. Roush

Born

May 8, 1893 at Oakland City, IN (USA)

Died

March 21, 1988 at Bradenton, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.