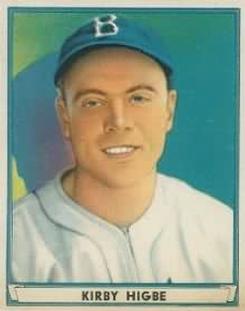

Kirby Higbe

Kirby Higbe, a good old boy from South Carolina was a hell-raiser all his life. He was a hard thrower who developed his fastball in childhood by tossing rocks and later saw it compared to Bob Feller’s. Higbe had a taste for alcohol and a lust for living that landed him in trouble a few times, but he was honest about himself, admitting he had made mistakes that he regretted.

Kirby Higbe, a good old boy from South Carolina was a hell-raiser all his life. He was a hard thrower who developed his fastball in childhood by tossing rocks and later saw it compared to Bob Feller’s. Higbe had a taste for alcohol and a lust for living that landed him in trouble a few times, but he was honest about himself, admitting he had made mistakes that he regretted.

Although a Southerner by birth, Higbe had some Northern roots. His paternal grandfather, Wellington William Higbe, was born in Akron County, Ohio in 1849, and served in the infantry for the Union Army after the Civil War. By 1870, Private Higbe was stationed in Warrenton, Georgia and then later married Mary Elizabeth Baugh of South Carolina; the two settled in Richland County and raised a family there. Wellington Higbe later became chief of police in Columbia, South Carolina.

Walter Kirby Higbe was born in Columbia on April 8, 1915. His father, Lloyd Wellington Higbe, was a glass blower and later a bottle salesman for Lauren’s Glass Works. Kirby adored his mother, Cynthia (Kirby) Higbe, a gentle, understanding church-going woman and regretted the trouble he caused her.

Kirby had an older brother, Lloyd, and a younger brother, Harold. In 1918, when the flu epidemic hit the nation, the family moved to Jacksonville, Florida, trying to escape the outbreak, but Harold contracted the disease and died. The family returned to Columbia to bury Harold. Subsequently, Lloyd and Cynthia had two more children—a daughter, Cynthia, and a son, Frazier.

The Great Depression hit the Higbe family hard. Kirby quit school after the seventh grade and took a job as a messenger boy for the Southern Railroad for $50 a month. He later regretted the decision to quit school but felt obligated at the time to help the family.

In 1931 Higbe left the railroad to take a job at Claussen’s Bakery and pitch on its baseball team. Later he pitched for an American Legion team. Higbe was a hard thrower who knew nothing of the mechanics of pitching.

Scouts from the Pirates took notice of his fastball and signed Kirby to pitch for Tulsa (Oklahoma) in the Western League in 1932. But he hit so many batters in batting practice, when the team broke camp Higbe was left behind with a catcher to work on his control. Only seventeen, he got homesick and returned to Columbia, where he pitched for a semipro team.

Higbe pitched briefly at the Class A level in each of the next two seasons. He went 1-4 in eight games for the Wichita/Muskogee Oilers of the Western League in 1933, and 0-2 in six games for Southern Association’s Atlanta Crackers in 1934. Higbe was with the Portsmouth (Virginia) Truckers in the Class B Piedmont League, a Chicago Cubs affiliate, in 1935. In his first full season as a professional, he had ten victories (10-13) and 206 innings-pitched. Higbe won eleven games and lost twelve while splitting the 1936 season between Portsmouth and the Columbia Senators of the South Atlantic League.

In 1937 the twenty-one-year-old Higbe went to spring training with the Cubs. Manager Charlie Grimm told him he had major-league stuff but needed seasoning. Grimm sent Kirby to the Moline (Illinois) Plow Boys in the Class B Three-I League, but promised to bring him back at the end of the season if he had a good year.

Kirby had a great year, going 21-5 and leading the league in wins, winning percentage, innings pitched, strike outs, and walks. Higbe gave credit for his new success to his new bride, nineteen-year-old Columbia native Anne Ellerbe, whom he married on May 27, 1937.

The Cubs did call him back, and Kirby got to pitch his first major-league game, against the St. Louis Cardinals at Wrigley Field on October 3, the last day of the regular season. He pitched the final five innings of Chicago’s 6–4 win, earning his first major league victory. In 1938, Higbe headed to Catalina Island, where the Cubs trained, but got homesick and went only as far as Knoxville, Tennessee. He called the Cubs and asked them if he could play at Birmingham and when they needed him he would come. The Cubs agreed and Kirby played for the Birmingham (Alabama) Barons of the Class A Southern Association until September, winning fifteen games before the Cubs recalled him.

The Cubs were five games behind the league-leading Pirates when Higbe made his first major-league start on September 8, 1938, at Sportsman’s Park, St. Louis. Chicago took the early lead but Kirby couldn’t hold it, giving up four runs over six innings. Higbe started again in the first game of a doubleheader in Philadelphia on September 23, lasting only four innings. He had pitched ten innings for the Cubs in two starts, allowing sixteen base runners and six runs, but years later he remembered feeling good about things. His homesickness was a thing of the past, and he felt he was in the big leagues to stay.

In 1939, Higbe pitched well early, mostly in relief, winning two games and losing one with a 3.18 ERA. On May 29, the Cubs traded him, along with pitcher Cowboy Harrell, and outfielder Joe Marty to the Phillies for pitcher Claude Passeau. Kirby went from the reigning National League champs to a perennial cellar dweller. Regardless of how well he pitched for the Phillies, it was hard to come up with wins. He was 10-14 for his new club, with a 4.85 ERA. His combined 123 walks for the two franchises led all National League pitchers.

In 1940 the Phillies were last again. Higbe, 14-19, again led the league in walks, but now also led in strikeouts. He was selected to the All-Star team, but did not play. While it may have been painful to play for a losing team, the regular work helped Kirby a great deal, work he likely would not have had on a pennant contender.

On November 11, 1940, Philadelphia traded Higbe to the Dodgers—who no doubt were influenced by his five 1940 victories over the Giants—for three players and at that time a whopping $100,000. Dodgers general manager Larry MacPhail said Higbe possessed the best curve ball in baseball and was sure to be a twenty-game winner for Brooklyn. The deliriously happy Higbe also got a salary increase to $10,000 a year.

The five-feet-eleven, 190-pound right-hander had his best year in 1941, winning a league-leading twent-two games and losing nine. Higbe established career highs in many pitching categories, including forty-eight appearances, thirty-nine starts (also leading the league in both categories), and 298 innings pitched. His performance was good enough for seventh place in the MVP voting.

Not surprisingly, Higbe loved playing in Brooklyn. The fans were great and he was with a top team. He acquired the name “Laughing Boy” from Dick Young of the New York Daily News, who noted that he had a grin as wide as that of comedian Joe E. Brown.

The Dodgers won the pennant, their first since 1920, and Higbe was their starting pitcher in Game Four of the World Series against the Yankees. He was behind, 3–0, when he left with two outs in the top of the fourth. The Dodgers rallied to take a 4–3 lead going into the top of the ninth. The stage was set for Mickey Owen’s infamous error allowing Tommy Henrich to reach first base and set up the Yankees’ miracle comeback. The Yankees closed out the Series the next day. It was Kirby Higbe’s only World Series appearance.

Higbe won sixteen and lost eleven in 1942 as the Dodgers won 104 games, only to finish two games behind the Cardinals. He was plagued by arm trouble after the season and in 1943 he had a mediocre 6-10 record in the middle of July. His arm came around however, and he won seven consecutive decisons, finishing a respectable 13-10.

On October 16, 1943, Higbe was drafted into the Army at Fort Jackson, near his Columbia, South Carolina home. He was assigned to the military police, which meant, essentially, standing guard, but he was primarily there to play baseball. That did not last, however, and Higbe was sent to Camp Livingston, Louisiana. There he underwent basic training and became a rifleman. He still managed to play some ball and was selected to play in the National Baseball Congress Semi-Pro tournament in 1944. He participated while on furlough and made the All-Star team.

In 1945, Kirby found himself in Germany. He was frightened as he went into combat at Cologne; seeing dead bodies shook him badly. His unit fought all the way to Berndorff, Austria. Shipped home after the war in Europe ended, Higbe and his fellow soldiers took more training and sailed for the Philippines. When they arrived there, they learned the Japanese had surrendered. While in the Philipines, Higbe managed the Manila Dodgers, and when he wasn’t playing baseball, he was selling beer to the locals.

Kirby was late getting to spring training in 1946 because he wasn’t discharged until late March, but he had a successful season, winning seventeen and losing eight with a career low ERA of 3.03. The Dodgers tied the St.Louis Cardinals for first place, but lost the pennant in major-league baseball’s first-ever playoff series, two games to none. Higbe relieved starter Ralph Branca in the first game and was the fourth of six pitchers Brooklyn used in the second contest. Kirby pitched in the 1946 All-Star Game in Fenway Park, a game won by the American League, 12–0. While he did not get the loss, he yielded four runs on five hits in one and a third innings, including the first of Ted Williams’s two home runs.

Baseball’s color line was broken in 1947, when Jackie Robinson was brought up from Montreal to Brooklyn. When Branch Rickey announced that Robinson was to play for the Dodgers, Higbe was one of a group of Brooklyn players who protested Rickey’s decision. Subsequently, Kirby was traded to the Pittsburgh Pirates on May 3, 1947 along with Hank Behrman, Dixie Howell, Gene Mauch, and Cal McLish in exchange for Al Gionfriddo and $100,000. After going 2-0, with a 5.17 ERA, for the pennant-winning Dodgers, he was 11-17, with a 3.72 ERA, for Pittsburgh. He walked 122 batters, leading the league for the fourth and last time in that category.

Higbe went 8-7 for the Pirates in 1948, pitching mostly out of the bullpen. He had a terrible start to the ’49 season, giving up twenty-three earned runs in fifteen and a third innings. On June 6, Pittsburgh traded him to the Giants for pitcher Ray Poat and infielder Bobby Rhawn. Pitching mostly in relief for the Giants, he was 2-2 for the season, and according to Tommy Henrich’s book, The Way To Better Baseball, was now almost exclusively a knuckleballer. Overall, he appeared in forty-four games for both clubs, but pitched just ninety five and two thirds innings, his lightest workload since 1938.

Higbe, now thirty-four years old, made his last major-league appearance on July 7, 1950, at Braves Field, pitching two scoreless innings in relief. On July 12, the Giants sent him to the Minneapolis Millers, their Class AAA affiliate in the American Association. Higbe finished his big-league career with 118 wins, 101 losses, a 3.69 ERA, and twenty-four saves. He was, however, very good during his five seasons with the Dodgers, going 70-38 with a 3.29 ERA.

Higbe won five games and lost eight for the first-place Millers in 1950. He also appeared in four games for the Pacific Coast League’s Seattle Rainiers, dropping two decisions. He did better in 1951, winning seventeen games for Class A Montgomery and Class AA Atlanta. He spent the entire 1952 season with Montgomery in the South Atlantic League, going 13-14 with a 2.79 ERA. Sliding down the minor league ladder, Kirby pitched in the Tarheel and Tri-State Leagues in 1953, winning eighteen games despite arm trouble. He pitched his last game with a semipro team and called it quits. For his twenty years of professional baseball, Higbe was inducted into the South Carolina Athletic Hall of Fame.

After twenty-six years as a ballplayer, Higbe was now just an ordinary working man. He landed a job with the post office in Columbia. Kirby began seeing another woman, Betsy Ains, whom he married in 1960 when their divorces were final. They had two sons, David Parks Higbe, born in 1961, and Hugh Whitlow Higbe, born in 1963. Hugh Whitlow Higbe, was named after Higbe’s two best friends in baseball—Hugh Casey and Whitlow Wyatt.

Kirby resigned from the post office and signed on with a chemical company, but that job evaporated in nine months, putting him out of work. Bills were piling up with no money coming in. A desperate Higbe wrote several bad checks and was ordered to pay them off. When he could not, he was sentenced to sixty days in the Richland County Jail.

A sympathetic guard got Higbe a job in the jail as a trustee, cleaning the cells. Higbe had his own room in the jail. Not only did he get out after forty days, but he got a job as a guard at the jail. He stayed there for two years, then quit, thinking he was about to get a better job with the South Carolina Tax Commission. That did not happen, and Kirby was out of work for six months.

Finally, he got a job at the state penitentiary as a guard. But Higbe could not keep out of trouble. To make extra money, he began smuggling sleeping pills into the prison for the inmates. He was eventually caught and pleaded guilty. The judge was lenient and gave Higbe a three-year suspended sentence and three years’ probation. Kirby got some relief when he started receiving $209.93 a month under the major leagues’ pension plan.

Higbe wished he had finished high school and taken advantage of the GI Bill to go to college. But he never regretted being a big-league ballplayer. He loved every minute of being in the majors. Also, he gave back to baseball and to young players, by coaching American Legion teams in his home town. Higbe died of emphysema on May 6, 1985, in Columbia, South Carolina, and is buried in that city’s Elmwood cemetery. He was seventy years old. Surviving were two sons, Hugh Whitlow Higbe and William Kirby Higbe.

Sources

Higbe, Kirby, with Martin Quigley. The High Hard One. New York: Viking Press, 1967.

Honig, Donald. Baseball When the Grass Was Real. New York: Coward, McCann and Geoghegan Inc., 1975.

James, Bill. The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract. New York: The Free Press, 2001.

James, Bill and Neyer, Rob. The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers. New York: Fireside, 2004.

Light, Jonathan Fraser. The Cultural Encyclopedia of Baseball. Jefferson, North Carolina, and London: McFarland, 1997.

“Ex-Dodger, Cub pitcher Kirby Higbe.” Chicago Tribune. May 8, 1985, p. A10.

“Feller, Higbe Hurled for Legion Also-Rans.” Sporting News. June 8, 1960, p. 20.

“Phils Sell Higbe to Dodgers for $100,000.” Chicago Daily Tribune. November 12, 1940, p. 21.

“USO All-Stars Top Manila, 5-4.” New York Times. January 4, 1946, p. 27.

Kirby Higbe file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum at Cooperstown, New York.

New York Times, Obituary, May 7, 1985

Bedingfield, Gary. “Kirby Higbe.” Baseball in Wartime (http://www.baseballinwartime.com/player_biographies/higbe_kirby.htm)

Kemp, Bill. Illinois-Indiana-Iowa League: Minor League Baseball in the Middlewest, 1901–1961. Three-eye.com (http://www.three-eye.com/playersH.html)

Full Name

Walter Kirby Higbe

Born

April 8, 1915 at Columbia, SC (USA)

Died

May 6, 1985 at Columbia, SC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.