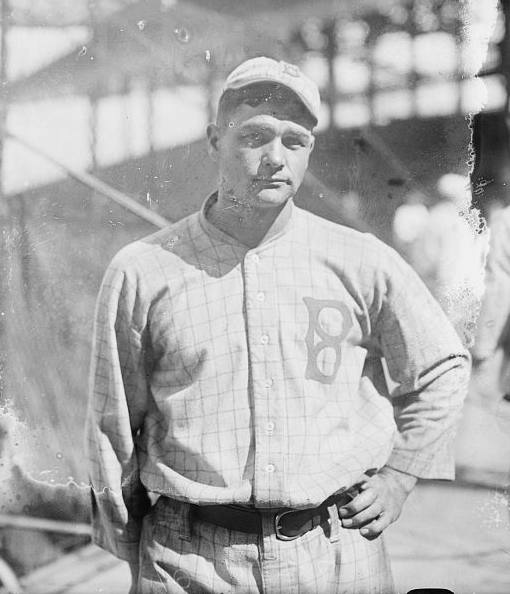

Zack Wheat

Zack Wheat remains the Dodgers all-time franchise leader in hits, doubles, triples, and total bases. Though he threw right-handed, Wheat was a natural left-handed hitter who corkscrewed his spikes into the dirt with a wiggle that became his trademark. Unlike most Deadball Era hitters, he held his hands way down by the knob of the bat, refusing to choke up. “There is no chop-hitting with Wheat, but a smashing swipe which, if it connects, means work for the outfielders,” wrote one reporter. He was an outstanding first-ball hitter, and he was also so renowned as a curveball hitter that John McGraw reportedly had a standing order prohibiting his pitchers from throwing him benders.

Zack Wheat remains the Dodgers all-time franchise leader in hits, doubles, triples, and total bases. Though he threw right-handed, Wheat was a natural left-handed hitter who corkscrewed his spikes into the dirt with a wiggle that became his trademark. Unlike most Deadball Era hitters, he held his hands way down by the knob of the bat, refusing to choke up. “There is no chop-hitting with Wheat, but a smashing swipe which, if it connects, means work for the outfielders,” wrote one reporter. He was an outstanding first-ball hitter, and he was also so renowned as a curveball hitter that John McGraw reportedly had a standing order prohibiting his pitchers from throwing him benders.

But even after years of hitting .300, it was Wheat’s stylish defense that won him the most admirers. “What Lajoie was to infielders, Zach Wheat is to outfielders, the finest mechanical craftsman of them all,” Baseball Magazine crowed in 1917. “Wheat is the easiest, most graceful of outfielders with no close rivals.” An extremely fast runner, Zack was as close to a five-tool player as anyone of his era. His only weaknesses were his poor base-stealing ability and proneness to injury (his tiny size 5 feet frequently caused nagging ankle injuries).

Zachariah Davis Wheat was born on May 23, 1888, at his family’s farm near Hamilton, Missouri, sixty miles northeast of Kansas City. Missouri was still a wild frontier then; just six years earlier, Jesse James was murdered by a member of his own gang in nearby St. Joseph. Zack was the eldest of three sons, all of whom played professional baseball. The middle brother, Mack, spent five years as Zack’s teammate with Brooklyn, while the youngest brother, Basil, was a longtime outfielder and catcher in the minors.

Their father, Basil Sr., was a descendant of Moses Wheat, one of the Puritans who fled England and founded Concord, Massachusetts, in 1635. Their mother, Julia Scott Wheat, was said to be a full-blooded Cherokee, but SABR research has shown this was likely a fabrication, dating from Zack’s early days as a professional. He was typically reticent on this topic, but despite a denial in his own words in 1916, his presumed Native American heritage was still widely discussed in baseball circles. In an era that also produced Jim Thorpe and Chief Bender, Wheat’s supposed Indian blood was thought by some to be the primary reason for his excellence. “The lithe muscles, the panther-like motions of the Indian are his by divine right,” Baseball Magazine wrote in 1917. The statement was repeated and accepted as an article of faith for more than a century.

Basil Sr. died when Zack was 16, and the Wheats moved to Kansas City, Kansas, where Zack got his start as a second baseman with the semipro Union Club. With his family nearly destitute, Zack set out to make a living as a ballplayer. In 1906 he went to Enterprise, Kansas, where he earned $60 per month playing for an independent team. That was followed by minor league stops in Fort Worth, Shreveport, and Mobile. Wheat quickly won a reputation as a top-notch defensive outfielder but was lackluster at the plate; years later he attributed his minor league batting averages of .260 in 1908 and .246 in 1909 to malaria he suffered in the southern cities. Traveling home from Mobile after the 1908 season, Zack stopped in St. Louis on September 20 to attend his first major league game. It was a doozy: the Browns’ Rube Waddell defeated Walter Johnson in 10 innings, 2-1, setting an American League record by striking out 17 batters. “After seeing those two pitchers, I wondered if I wanted to be a big leaguer and have to hit against pitchers like them,” Wheat remembered. As it turned out, he wouldn’t have to worry about Waddell or Johnson; Wheat was destined for the National League.

On the advice of scout Larry Sutton, Brooklyn purchased Wheat’s contract from Mobile for a reported $1,200 on August 29, 1909, and that September Zack batted .304 in 26 games for the Superbas. “He is an Indian, but you would hardly guess it except from his dark complexion,” wrote one newspaper shortly after Zack’s arrival in Brooklyn. “He is a very fine fellow and a quiet and refined gentleman.” In 1910, his first full major league season, Wheat finally became the offensive threat he had never been in the minors, leading the Dodgers with a .284 average while ranking among the league leaders in hits (172), doubles (36), and triples (15). “I was young and inexperienced [in the minors],” Wheat explained. “The fellows that I played with encouraged me to bunt and beat the ball out. I was anxious to make good and did as I was told. When I came to Brooklyn I adopted an altogether different style of hitting. I stood flat-footed at the plate and slugged. That was my natural style.”

Nobody could argue with the results. “The beauty of Wheat’s hitting is that many of his drives go for extra bases,” wrote one reporter. Over the next several seasons Wheat established himself as “one of the most dreaded and murderous sluggers in the National League,” ranking among the league leaders in home runs every year from 1912 to 1916. Five of his nine homers in 1914 were of the over-the-fence variety, considered a remarkable achievement at the time. Wheat was far ahead of his time in many aspects of hitting, adopting strategies that wouldn’t be widely accepted until decades later. He was sometimes criticized for his reluctance to bunt, but he argued that he was more valuable to the team by swinging away. Zack also came to favor a lighter bat than most (40 ounces), which enabled him to generate more bat speed. “I am an arm hitter,” he explained to F. C. Lane. “When you snap the bat with your wrists just as you meet the ball, you give the bat tremendous speed for a few inches of its course. The speed with which the bat meets the ball is the thing that counts.”

On May 13, 1912, Wheat skipped a game at Cincinnati to marry Daisy Kerr Forsman, his 25-year-old second cousin, whom he had first met only two months earlier when the Superbas played an exhibition series in her hometown of Louisville. When the Brooklyn players found out that the couple had eloped, they decorated a “bridal suite” on the team train to St. Louis. It was the start of a tradition: In later years, Wheat’s family almost always accompanied him on train trips cities around the circuit. In marrying Daisy, Zach acquired not only a wife but an agent, as well. “I made him hold out each year for seven years,” Daisy remembered, “and each time he got a raise.”

In the offseason Wheat raised stock — during World War I he sold mules to the Army to serve as pack animals on the battlefields of Europe — and he used the second job as leverage in contract negotiations. “I am a ball player in the summer and a farmer in the winter time,” he said, “and I aim to be a success at both professions.” Unless Brooklyn met his demands each spring, Zack was perfectly content to stay on his farm in Polo, Missouri. In an era when the balance of power rested entirely with the owners, the threat of a holdout was the only negotiating tool he had. Because of his contract difficulties, trade rumors seemed to surround Wheat every winter. But the Dodgers never pulled the trigger, perhaps because Brooklynites loved Wheat so much that, as one local newspaper wrote, “They regard Zach and his wife and his two children as members of their own families.” By 1926, his last year with Brooklyn, Wheat was making $16,000 as player and assistant manager.

Later in 1912, Wheat recommended that Brooklyn sign an old friend of his from Kansas City, a former youth basketball teammate who was showing promise as a minor league outfielder. The Superbas agreed, and Wheat and his boyhood friend — Charles Dillon Stengel, better known as “Dutch” — played together in the Brooklyn outfield for seven seasons. Later Stengel gave Wheat much of the credit for his success in baseball. “I never knew him to refuse help to another player, were he a Dodger or even a Giant,” Stengel said. Wheat had a mild temperament on and off the field, and was said to have never been ejected from a game. “I never saw Wheat really angry,” Stengel said, “and I never heard him use cuss words.” Wheat, however, did have his vices. “I smoke as much as I want and chew tobacco a good deal of the time,” he once said. “I don’t pay any attention to the rules for keeping in physical condition. I think they are a lot of bunk. The less you worry about the effect of tea and coffee on the lining of your stomach, the longer you will live and the happier you will be.”

In 1916 Wheat had a magnificent season, batting .312 while ranking among the NL leaders in virtually every offensive category. He also set a Brooklyn record by batting safely in 29 consecutive games. Even better, for the first time in Wheat’s career the Dodgers found themselves in a pennant race. In the closing weeks of the season Wheat became so excited that he was unable to sleep at night. “I was thinking and dreaming and eating pennants,” he recalled. “I used to get up in the middle of the night and smoke a cigar so that I could calm down a little and get some sleep.” Brooklyn eked out the pennant but lost the World’s Series handily to Boston, as Red Sox pitchers held Wheat to a miserable .211 batting average.

In 1919 Wheat was appointed captain of the Robins, and that season marked a turning point for both Wheat and the game he loved. Over the last decade of the Deadball Era, Wheat compiled more total bases than any other National Leaguer, and in hits he ranked second only to longtime teammate Jake Daubert. But as great a Deadball hitter as he was, Wheat’s powerful stroke enabled him to take advantage of the new lively ball like few others. In 1920 he led the Dodgers to the pennant while setting new career highs in hits (191), runs scored (89), and slugging percentage (.463). In the first six years of the lively ball he averaged .347. In 1923-24 Wheat posted back-to-back .375 batting averages, and in 1925 he had one of the best seasons ever by a 37-year-old: a .359 batting average with 125 runs scored, 221 hits, and a .541 slugging percentage.

A subtle but longstanding friction existed between Wheat and manager Wilbert Robinson, stemming largely from Robinson’s belief that Wheat always seemed to be pursuing the manager’s job behind his back. When Charles Ebbets died in 1925, new team president Ed McKeever pushed Robinson into the front office and named Wheat as player-manager. Newspapers confirm that he managed the Dodgers for two weeks. But McKeever caught pneumonia at Ebbets’ funeral, died soon afterward, and Robinson returned to the helm. In 1931 Steve McKeever, Ed’s brother, hired Wheat as a coach, leading to widespread speculation that Zack was being groomed for the manager’s spot. Robinson, whose job was being threatened by Wheat for a second time in seven years, treated his former star as coldly as ever. As it turned out, Wheat never again managed in the majors, much to his disappointment. When Wheat was in his 70s, a reporter asked him why he hadn’t stayed in baseball. “Nobody asked me to,” he replied. To add insult to injury, Wheat’s 1925 managerial stint never made it into the official records.

In 1927 the Dodgers decided they no longer needed Wheat. In recognition of his many years of service, the club released him rather than trade him so he could negotiate his own deal with whomever he chose. After being wooed by the Giants, Yankees, and Senators, Wheat signed a $15,000 contract with the Philadelphia Athletics and batted .324 in part-time duty there. In 1928 he signed with Minneapolis of the American Association, batting .309 before suffering a bruised heel that put him on the shelf for the season and, as it turned out, forever. Wheat decided to retire from baseball in 1929. At the time, his 2,884 hits were tenth on the all-time major league list, while his 4,100 total bases ranked ninth.

Wheat turned to farming full-time after leaving baseball, but the Great Depression lowered prices so dramatically that in 1932 he was forced to sell his 160 acres for just $23,000. He moved his family to Kansas City, Missouri, where he operated a bowling alley for a time before becoming a patrolman with the Kansas City Police Department. He nearly died on Easter Sunday 1936 when he crashed his patrol car while chasing a fugitive, suffering a fractured skull, dislocated shoulder, broken wrist, and 15 broken ribs. After five months in the hospital, Wheat moved with his family to Sunrise Beach, Missouri, a resort town on the shores of the Lake of the Ozarks, to recuperate. As it turned out, Wheat spent the rest of his life in Sunrise Beach. Always an avid hunter, he opened a 46-acre hunting and fishing resort, which became a popular destination for ex-ballplayers. One of his favorite activities was turning on his radio and television simultaneously to listen to two different ballgames at once. Occasionally he and Daisy drove to Kansas City or St. Louis to see a game in person.

In 1957 Wheat was voted into the Hall of Fame by the Veterans Committee, but there was only one problem: He was ineligible for election by the veterans because he’d been retired for less than the requisite 30 years. The committee rectified the mistake at its next meeting in 1959 when it unanimously elected the newly eligible Wheat. “That makes me feel mighty proud,” the 70-year-old Wheat said. “I feel a little younger, too.” But Zack’s joy turned to sadness later that year when his wife, Daisy, passed away. Zack Wheat died on March 11, 1972, at a hospital in Sedalia, Missouri. Shortly before his death he was asked if he had any advice for youngsters with ballplaying aspirations. “Yes,” he said. “Tell them to learn to chew tobacco.”

Note: A slightly different version of this biography appeared in Tom Simon, ed., Deadball Stars of the National League (Washington, D.C.: Brassey’s, Inc., 2004).

Sources

For this biography, the author used a number of contemporary sources, especially those found in the subject’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Full Name

Zachariah Davis Wheat

Born

May 23, 1888 at Hamilton, MO (USA)

Died

March 11, 1972 at Sedalia, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.