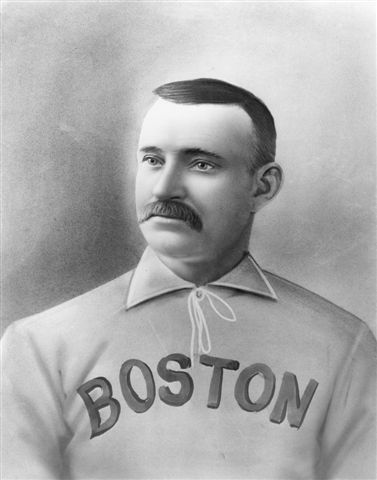

Old Hoss Radbourn

Charles Radbourn’s pitching achievements were hailed by contemporaries and sportswriters for decades as some of the greatest feats of nineteenth century baseball. Little known today, many considered an 18-inning game in 1882 as the finest athletic contest ever seen on a baseball diamond. That game was won, not by the pitcher Radbourn, but by the batter Radbourn playing right field. After a scoreless 17 1/2 innings, he clubbed one over the left-field wall for the first walk-off home run in a 1-0 game in major-league history.

It was on the mound, though, where Radbourn truly shined. His winning 60 games in 1884 was long viewed as the greatest of all pitching feats. (Some reference sources cite him with 59 wins, a discrepancy arising from determining who should be credited with the victory in his July 28 relief appearance.) Throughout his lifetime and well into the career of Cy Young, Radbourn was hailed as the “King of Pitchers.” He had an easy underhand motion from which he delivered a variety of pitches from varying arm angles. He was one of the first to truly dicker with his delivery day in and day out to keep hitters off balance, a trait expanded upon by Clark Griffith and Eddie Plank at the turn of the century.

Radbourn was a tireless worker who didn’t seek the limelight. As one observer noted, he “never worked the press or catered to the grandstand, and was, in fact, so (in)different to applause or criticism that people who didn’t know him well, regarded him as surly and capricious.”1 Year after year, he just took his turn in the rotation and produced what many of the era considered the finest career of all the hurlers.

Caroline (nee Gardner) Radbourn packed her possessions in the summer of 1851 and left Bristol, England with her daughter Sarah, headed for a new life in the United States. Her husband Charles had already relocated to America. Caroline and Sarah traveled with Charles’ brothers James and George and his wife Emily and their children. They arrived in New York City on August 22, 1851 aboard the ship Mary Ann Peter. The families moved to Rochester where they stayed until 1855. There, Caroline gave birth to Charles on December 11, 1854.

In 1855, the families moved to McLean County, Illinois. Charles and Caroline, both born circa 1827, settled in the town of Martin while George and Emily settled in Bloomington. Soon, Charles and Caroline and family joined their kin in Bloomington, purchasing a farm on West Washington Road. In April 1856, Emily gave birth to George Radbourn, Charles’ first cousin and also a future major leaguer. Initially, Charles, a butcher by trade, worked the family farm where his parents George and Sarah and his brother James also resided. In May 1857, he opened a meat market in town. In all, Charles and Caroline had eight children: Sarah, born circa 1848; Charles; John, born circa 1856; William, born circa 1858; Albert, born circa 1861; Selina, born circa 1862; Minnie, born circa 1856; May, born circa 1858.

Some sources claim that the younger Charles Radbourn’s middle name was Gardner, his mother’s maiden name. That may be but as a child he was usually referred to as Charles Jr. Radbourn attended local schools in Bloomington. In his late teens, he worked as a butcher in a slaughterhouse with his father and as a brakeman for the IB&W Railroad, traveling to Indianapolis and back. Contrary to rumors throughout his baseball career, Radbourn was not a veteran of the Civil War; in fact, he was only 10 years old when it ended.

Radbourn, a right-hander, loved to hunt and play baseball. He strengthened his arm as a teenager by repeatedly throwing the ball against a barn on his family’s farm. At least by 1874, he was playing baseball for the main Bloomington nine, earning extra money on weekends and holidays. He also played some games as a ringer for Illinois Wesleyan University. With the Bloomington squad, he predominantly played third base. His older cousin Henry was the pitcher. Of note, a game-fixing scandal rocked the Bloomington Reds in 1876.

In Bloomington on September 1, the Reds lost to Springfield 4-1. Radbourn went 1-for-4 and committed five errors in left field. In total, the club made 14 miscues, 10 of which were made between the left fielder and center fielder Gleason. Per the Bloomington Pantagraph, “The amount of betting that was done…was considerable.”2 Gamblers Edward Stahl, Edward Fifield and Jim Connors were present taking as many wagers as possible in favor of Springfield. At the end of the contest, a shouting match took place between the gamblers and fans, as many suspected that the contest was “set up.” Henry Radbourn entered the fray, confronting the three men and accusing them of offering bribes. Later that night in fact, three players, Gleason, Roach, and Flynn, were seen at Connors’ hangout having a “jolly good time” on the gambler’s dime.

Later the Pantagraph interviewed Charlie Radbourn. He admitted to drinking heavily the night before the contest and to having a conversation with two gamblers at Schausten’s Saloon. “He says he had a talk with these two, but can not remember distinctly what the talk was more than that it was in relation to throwing the game. After the talk Radbourn went over to two butchers in the saloon and told them about the talk. The butchers say that Charlie told them that Stahl and Connors offered him $25 if he would throw the game…He does not deny that he may have said that he would take the money, but, being drunk, was not responsible for his words.”3 Henry Radbourn, also at the bar, backed his story. Stahl approached Charlie again in the morning before the game, offering $75 total to the two Radbourns and catcher Sue Allen. “Charley having refused the offer told this at once to H. Radbourn who also declined.”4 On September 3, the stockholders met and expelled Gleason and Roach from the club. Flynn was exonerated as was the inebriated Radbourn.

Charles continued with the Bloomington club through 1877, the year he started pitching regularly. During this time, he played with future major leaguers Jack and Bill Gleason and Cliff Carroll. Radbourn’s best friend growing up was Bill Hunter, a pitcher for the Bloomington team. One Baseball Magazine story claims that future major leaguer Dave Rowe, a resident of Illinois in the mid-1870s, taught Hunter and Radbourn how to throw a curveball, effectively launching Radbourn’s career in the box.5 Al Spalding regaled audiences with a description of his first meeting with Rad during an exhibition game in Bloomington around this time with his Chicago White Stockings. Radbourn relieved his cousin in the contest. As he warmed up, the Chicago players chuckled because the reliever twisted his body to face second base before delivering the ball to the plate. Spalding acknowledged that their smiles soon dissipated as Radbourn sent one batter after another back to the bench.

In 1878, a promoter named William Morgan organized an independent professional team in Peoria, less than 40 miles from Bloomington. The club, known as the Reds, was Peoria’s first professional nine. It was captained by Tom Loftus and included several Bloomington-area favorites, including the Gleason brothers, Carroll and Radbourn, now 23 years old. Also on the club were Dave and Jack Rowe, William H. Taylor, and Henry Alveratta. Radbourn was paid $40 a month for the three-month period from July through September. At times, Peoria played exhibition games against National League clubs, racking up wins versus Milwaukee, Chicago, Hartford and Boston in the process. Radbourn played right field and change pitcher, the club’s second pitcher. In 28 games he batted .299.

On April 1, 1879, Ted Sullivan, one of the game’s foremost organizers, formed and ran the Northwest League which consisted of three clubs from Illinois — Davenport, Omaha, and Rockford, and Dubuque, Iowa. It was the first so-called minor league formed outside the east coast. Sullivan took steps to set a salary structure for the Northwest League and clearly subordinated the league to the National League, which to some establishes it as the first legitimate minor league. Sullivan ran the Dubuque team which was financed by Iowa’s U.S. Senator William B. Allison and future Congressman and Speaker of the House David B. Henderson.

Before the season began, the Milwaukee National League team lost its charter and the club’s best players en masse joined Rockford. Sullivan countered by signing many of the Peoria players. Radbourn signed up with Dubuque in March with Peoria teammates Loftus, the Gleason brothers, Alveratta, and Taylor. Also playing on the club were Charles Comiskey, Laurie Reis, Bill Lapham and Sullivan. Radbourn was paid $450 for the season, playing second base, the outfield and change pitcher. In one game on May 23, he made an incredible 15 putouts from second base. On August 4, he defeated the Chicago National League squad 1-0. Cap Anson later recalled, “in my fifteen years as premier batsman of the game, I never faced a pitcher who baffled me more completely with his curves than did Radbourn on the occasion of that memorable game in Dubuque…I do not hesitate to say that not one of the old school pitchers, or any of the later slabmen, could equal the famous Radbourn.”6

That year, Dubuque was one of the top clubs in the country not associated with the National League. The club ran away with the Northwest League pennant. Per the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, Rad played in 47 games, placed 72 hits for a .337 batting average and scored 31 runs. By December, he was negotiating with Buffalo in the National League. The following appeared in the Bloomington Pantagraph on January 9, 1880: “Yesterday, Mr. Charley Radbourn received a letter from the secretary of the Buffalo base ball club, asking for his photograph and his record as a base ball player made last season; also to state the lowest salary for which he would play in the Buffalo nine during the coming season. He answered the letter, and in all probability an arrangement will be made during the next week. The Providence club some weeks ago offered Charley a place at $800 for the season of ’80, but he declined the offer.”7

During spring training in 1880, Radbourn strained his shoulder and never pitched for Buffalo. He made his major-league debut on May 5 in Cleveland, batting sixth and playing right field. He went 1-for-4 but Cleveland romped to a 22-3 victory. Unable to pitch, he was released after six games in May, three at second base and three in right field. Rad returned to the slaughterhouse in Bloomington believing that his baseball career was over.

Over the winter, he received several telegrams with baseball offers but ignored them. In January 1881, Bill Hunter answered a telegram from Providence pretending to be Radbourn and agreeing to join the club in the spring for the same money offered by Buffalo the previous year. Hunter then borrowed money from his father to send Rad to Hot Springs, Arkansas to get into shape. He also got Providence to advance $100 to cover the expenses. Somewhat reluctantly, Radbourn embarked on his major-league career. He officially signed on February 7. Providence finished in second place, nine games behind Chicago. Rad shared the pitching duties with Monte Ward through much of the season. He started 36 games and relieved in another five, amassing a 25-11 record and 117 strikeouts and finishing in the top 10 in most pitching categories including a league-leading win-loss percentage. He also played 25 games in the outfield and 13 games at shortstop.

Charles Radbourn, at 5-foot-9 and listed at 168 pounds, entered baseball during the underhand pitching era. There is some evidence that he threw overhand at least occasionally, as noted later. He was what was then known as a “strategic pitcher.” In short, he used whatever assets he had to get batters out, not predominantly relying on speed. This is not to say that he wasn’t a hard thrower; he was indeed. He threw a rising fastball, screwball, sinker, slow curve, and something Ted Sullivan described as a dry spitter. He tossed the ball from varying arm angles, possessed great control and changed speeds constantly. He was perhaps the most resourceful of all nineteenth century pitchers, something he passed on to fellow Bloomington resident Clark Griffith. Per Ted Sullivan, who considered Radbourn the greatest of all pitchers, “From the time I met Rad, he was continually inventing a new delivery and trying to get it under control. He had a jump to a high fastball, an in-shoot to a lefthanded batter, a drop ball that he did not have to spit on, and a perplexing slow ball that has never since been duplicated on the ball field. When he let fly with the high fastball, he threw it so hard he actually leaped off the ground.”8

The Cleveland Herald believed the key to his success was the changeup: “A skillful change of pace is the most valuable item in a pitcher’s work, as Radbourn’s success — due chiefly to it — proves. The so-called ‘drop’ is either a ball started at the shoulder and slanting in its course, like (Hugh) Daily’s, or a skillfully-delivered slow ball, dropping naturally through lack of speed, such as (Jim) McCormick and Radbourn use.”9 Some writers even printed later that Radbourn was the originator of the changeup. Of course this wasn’t true but it’s a testament to the respect his slow ball gathered.

He threw “a very short, sharp curve.” The Topeka State Journal described his technique: “Charley Radbourn gets his curves without the use of his body. Having long fingers, he can get a firmer hold than most men, and then he never depends on wide curves, preferring to keep them so a batsman will hit out and get the ball on the end of his stick or close to the handle.”10

Radbourn wasn’t above doctoring the ball to gain an edge. He taught Griffith how to cut a ball with his spikes or any available object to gain a firmer hold for the sinker. He tried anything to stack the deck in his favor. As the Milwaukee Sentinel confirmed, “Radbourn was the first pitcher to introduce stepping around the box before delivering the ball. He also tried to work a new wrinkle by making the ball hit in front of the plate and bound over. It was legitimate, but the umpire would not allow it.”11 He wasn’t above pitching around the top batters to face lighter hitters; in fact, it was a common ploy. A Washington Post article in 1883 claimed that, “Radbourn, pitcher of the Providence nine, can pitch either right or left handed.”12 There doesn’t seem to be much supplementary evidence to support the claim, but it seems like something such a resourceful pitcher might try. In the era of no gloves, the batter wouldn’t know which hand the delivery was coming from until the pitcher went into his windup.

A former infielder and outfielder, Rad was known as one of the top fielding pitchers of his era. He also controlled the pitch selection and gave his own signals throughout his career, even after it was common for catchers to give most of the signs. Typically, he only signaled for outside pitches, mainly the curve. Rad practiced with an iron ball, throwing it underhand to develop arm strength. He also long tossed to get his arm in shape before taking the mound. He babied his arm, soothing it with hot towels and getting frequent messages. As a result and despite racking up more innings than most, he was one of the few major-league pitchers prior to Cy Young to attain a good amount of success after age 30.

Radbourn appeared in 83 games for Providence in 1882, 54 of them on the mound totaling 474 innings. Either Monte Ward or Rad started every game, 32 and 52 respectively. Rad posted a 33-20 record with a league-leading 201 strikeouts and a second-place mark in victories. The Grays fell only three games short of the championship. On August 17, he played right field versus Detroit. There was no score for the first 17 1/2 innings. In the bottom of the 18th, Rad hit a home run over the left-field wall against Stump Wiedman to claim the victory. It was the first walk-off homer in major-league history in a 1-0 game. Surprisingly by today’s standards, the contest only took 2 hours 40 minutes.

The American Association challenged the National League monopoly as a major league in 1882. By the end of the season, quite a few National League players were dissatisfied with their contracts. The AA seemingly was offering bigger paydays. In October, Radbourn signed with the St. Louis Browns in the AA, reuniting with the Gleason brothers, Charles Comiskey and Ted Sullivan. Providence teammates Art Whitney and Jerry Denny also signed with the Browns. Several other National Leaguers signed with Association clubs. In response, the National League threatened to blacklist the jumpers. Most, including Radbourn and the other Providence players, re-signed with their old clubs.

Providence fell to third place in 1883 but the word fell is misleading as they landed only five games out of first place. Rad tossed a no-hitter on July 25 versus Cleveland, an 8-0 win on the road. He took on the lion’s share of Providence’s pitching that season, appearing on the mound for 632 1/3 innings. Many know that Rad owns the single-season victory record with 60 in 1884 but few realize that he already owned the record. His 48 in 1883 set the major-league mark. The 300-strikeout mark was surpassed for the first time in ’83. Rad amassed 315 along with Jim Whitney in the National League and Tim Keefe in the American Association. The new heights can be partially attributed to the expanded schedule, as each team played over 90 games for the first time. After the season, Radbourn joined Sullivan on a barnstorming trip through the south. The roster included Buck Ewing, Comiskey, Tony Mullane, and Pete Browning among others. In November, it was reported that Rad signed with Providence for $2,000. As the Cleveland Herald put it, “Radbourn has signed with Providence for about half of the $4000 called for…”13 Obviously, he wasn’t happy even before the new season started.

Eighteen eighty-four is often the main focus of Radbourn’s career. Fifty-nine wins is hard to ignore. The pure numbers are staggering by today’s standards. Rad took the mound in 75 different games. He started 73 of those and finished every one. He shut out opponents 11 times and that was one of the few figures that didn’t lead the league. In 678 2/3 innings, he struck out 441 batters and posted a miniscule 1.38 ERA, a figure less than half the league average. Always impressive, Radbourn ceded fewer combined hits and walks than innings pitched. He won more than 83% of his decisions for a 60-12 won-loss record. Rad’s success in ’84 and his commitment to take the mound virtually every day towards the end of the season mark his campaign as perhaps the finest any pitcher ever entered into the books. The wear and tear would have a lasting consequence to the health of his right arm and his subsequent effectiveness.

The year started out on a somber note. On February 8, reports circulated out of Bloomington that the great Radbourn was shot in the thigh in a tiff with a female acquaintance. Luckily for baseball fans, it was actually one of Radbourn’s cousins that suffered the injury. For the first time, the National League allowed pitchers to raise their arm above their shoulder, effectively legalizing the overhand delivery. The ruling sparked a great deal of controversy throughout the summer and into the following winter. Many feared that pitchers had gained too great an advantage. The American Association avoided the debate; their pitchers were still bound by the previous rules, which in truth were hard, if not impossible, to enforce. Pitchers always had and always would push the boundaries.

Radbourn’s disgruntlement with his salary spilled over into spring training. Twenty-one-year-old Charlie Sweeney entered the season as Providence’s other main starter. He pitched the lion’s share of the games in the spring and was paid extra to do so which antagonized Radbourn, who also didn’t care for the gushing plaudits that were being heaped on his young colleague. Once the season began, Radbourn took his place in the rotation. Through June, the pair started all but one of the club’s 47 games, with Radbourn starting 24 of them. Sweeney, perhaps sore from the new overhand pitching style, fell out of the rotation on June 27. Radbourn was forced to fill in, starting and finishing 10 of the next 12 games. He wasn’t happy about it, especially considering he didn’t receive extra cash as Sweeney had during the preseason. It’s obvious that Sweeney and Radbourn were having some sort of a running feud, as Rad pitched that many games straight at least twice the previous season without complaint. After a loss on July 12, a local newspaper, the Providence Journal, described the pitcher as acting “careless and indifferent.”14 It seems he was drinking heavier than usual during this time as well.

In those 10 games, Rad posted a so-so 6-4 record. On July 16, he lost to Boston 5-2 after becoming erratic and ceding a couple runs in the eighth after being called for a balk. Providence management immediately suspended him because of poor play. Per the Boston Advertiser, “There have been unpleasant reports of the dissatisfaction of Radbourne (sic), pitcher of the Providence club, current for some time. This evening the board of directors of the Providence association decided to summon him to appear before them tomorrow and answer certain questions regarding his conduct for the past three weeks.”15 Baseless accusations were even mounted that perhaps he was throwing games. The Boston Globe described his frame of mind; “Radbourn was in no condition, physically or mentally, to pitch.”16 He apparently snapped in the eighth in a dispute with the umpire and his catcher Barney Gilligan. The sloppy play included a walk, an error by Gilligan, a fumble by the third baseman and the balk call on an apparent third strike. “This seemed to break up Rad, and then he pitched the ball so wild that no man could hold it, and two men came home.”17

Cyclone Miller started the next two games and Ed Conley the following. Sweeney relieved in two of the games and wasn’t pleased about being pressed into action. The team wanted Sweeney to pitch on the 21st in an exhibition game in Woonsocket, Rhode Island. He wouldn’t and the club scrambled to fill the role, using three pitchers including their backup catcher Sandy Nava. Sweeney did start the next day against Philadelphia. With a 6-2 lead after seven, manager Frank Bancroft pulled Sweeney, merely to give him some rest, and sent him to right field. He refused to go, cursed his manager, walked off the field, dressed and left the grounds. It seems Sweeney was doing a bit of drinking himself which added to his sour attitude. Providence, with only eight men on the field, yielded eight runs in the ninth and lost. That night, he tied one on again and refused to report the following day. Providence immediately expelled their only legitimate, eligible starter. It was later learned that Sweeney had been in consultation with the St, Louis club of the Union Association who happened to be playing in nearby Boston. Not coincidentally, he soon joined them.

The Providence directors met to decide how to proceed with the rest of the season, or if to proceed at all. Few viable starters were available on the market with rosters stretched thin with upwards of 33 clubs that season spread over three major leagues. Their record stood at 43-19-1, a mere 2 1/2 games behind first-place Boston in the standings and 5 1/2 games up on third-place New York. After falling so close to the pennant in previous seasons, all of Providence wanted the chance to seize first place. Bancroft consulted with Radbourn and the directors. Ultimately, Rad agreed to pick up much of the slack through the rest of the season for consideration. In his words, “I’ll pitch every day and win the pennant for Providence, even if it costs me my right arm.”18 First, the reserve clause was stricken from his contract, allowing him to become a free agent at the end of the season. Second, his salary was raised substantially; in essence, Radbourn was paid the salary of two pitchers for the remainder of the season. Third, fearing that he was also in consultation with the Union Association, management gave him $1,000 according to newspaper accounts. In total, he made upwards of $5,000 in 1884, one of the highest figures in baseball history to date.

Of the remaining 51 games, Radbourn started 41 of them. In those starts, he put up an eye-popping 35-4-1 record, virtually single-handedly driving the club to the pennant. He won eighteen straight from August 7 to September 6, a new major league record, including an incredible 14 victories in August. He started all but one game between August 9 and September 24, amassing a record of 24-4 during the span. That August 7 victory put Providence in first place permanently. To be sure, the daily grind took its toll on the pitcher. Bancroft, who roomed with Radbourn in ’84, later declared, “His showing was all the more remarkable and phenomenal when one knows that this great pitcher suffered untold agony in endeavoring to attain the goal for which he worked so hard and so pluckily. Morning after morning upon rising he would be unable to raise his arm high enough to use his hair brush. Instead of quitting he stuck all the harder to his task, going out to the ballpark hours before the rest of the team and beginning to warm up by throwing a few feet and increasing the distance until he could finally throw the ball from the outfield to home plate.”19 His arm was also being massaged nightly by Bancroft, teammates, porters, doctors or anyone available.

Providence won the pennant by 10 1/2 games over Boston; it was the club’s only championship. In October, the club met the winners of the American Association, the New York Metropolitans, in an impromptu World Series, the first of its kind. Naturally, Radbourn started and finished each contest. After the first game the New York Times commented, “The curves of Radbourne (sic) struck terror to their hearts, and they fell easy victims to his skill.”20 He only ceded two hits “and one of these is doubtful.”21 The series lasted three games; Rad won each. In 22 innings, he struck out 17 and allowed only 17 hits and no walks.

The season was extended in 1884, about 15 games per team. Radbourn started 73 of the club’s 114 games, plus exhibition contests and the World Series. Much is made of this heavy workload, and rightfully so, but it must be tempered slightly. For one, he pitched nearly as many innings in 1883, starting 68 of the club’s 98 games. To kick off that season, he pitched the Grays’ first 12 games and pulled off a similar 11-game streak in July. Secondly, 1884 wasn’t that far removed from the era of one-man or one-man dominant rotations. Radbourn’s 1883 season is an example of the latter. Pud Galvin (75 of 98) of Buffalo did much the same in ’83, as did Jim McCormick (67 of 84) with Cleveland in 1882 and Jim Whitney (63 of 83) of Boston in 1881. The same could be said for McCormick (74 for 85), Mickey Welch (64 of 83), Lee Richmond (66 of 85), and Will White (62 of 83) in 1880.

As promised, Providence offered Radbourn his release after the season but they also extended him a new contract, a lucrative one. He slept on it and signed the next day, apparently all the ill-will had melted away. Part of his motivation to stay in the Providence area was a budding relationship with Caroline (Carrie) S. Stanhope from Newport, Rhode Island. National League opponents wanted to limit Radbourn’s dominance and others that seemingly benefited from the rule permitting pitchers to extend their arms. At their November meetings, some executives pressured to have “pitchers to lower the arm to the shoulder. This, however, was opposed by the delegate from Providence. They were fearful that this would impair the effectiveness of their crack pitcher, Radbourne (sic), and fought stubbornly against it.”22 Note the inference here that Radbourn actually used an overhand delivery, at least as part of his arsenal. In the end, the league didn’t adjust the rule but they did institute another measure pointed at Radbourn. The new regulation forced pitchers to keep both feet on the ground at the time of delivery. Ostensibly, the rule was instituted to protect base runners from tricky pickoff moves by pitchers. In truth, though, it was none too subtle slap at Rad who used a little hop during his delivery to get some extra oomph on the ball. It proved highly unpopular and impractical and was abandoned after a month into the following season.

Radbourn turned in a solid, if unspectacular, season in 1885 after coaching the pitchers at Brown University in the early spring. In 49 games he posted a 28-21 record with only 154 strikeouts. Providence dipped as well, finishing in fourth place with a sub-.500 record and 33 games out of contention. Rad butted heads with management once again at the end of the season. On September 11, he was hit hard, giving up 15 hits and three wild pitches in a 9-1 loss to New York. The club directors suspended him for “indifferent work.” Said Radbourn, “I tried to pitch the best I could.”23 As the New York Times noted, that wasn’t good enough for club management. “Director (J. Edward, ‘Ned’) Allen (of the Providence club) said that all his players would be summarily dealt with in the future, and he would compel them to play good ball or they would not play at all.”24 The charge of corruption was on the other foot this time though as the New York Times printed: “A dispatch from Providence says: “The published statement to the effect that the management of the Providence nine intended to throw games to Chicago in order to defeat New York in the fight for the pennant has caused much excitement and comment here. The management emphatically (denies) that they propose to favor Chicago as against New York. The latter may be true. The work, however, of releasing (Arthur) Irwin and suspending Radbourn and (Jerry) Denny, thus losing the services of the three strongest players of the team at a critical stage of the contest, affords food for conjecture.”25 Rad remained suspended through the rest of the season.

In truth, the suspension may have been financially motivated, a cost-cutting measure; soon after the season ended, Providence disbanded. Formally, the entire roster was transferred to league control. National League executives fought over the talent. President Arthur Soden of the Boston Beaneaters claimed Radbourn and catcher Con Dailey. Rad worked another solid year in ’86, pitching in 58 games with a 27-31 record. After a bit of dickering, he signed with Boston for about of $4,800 in November, the highest figure in the game trailed by Fred Dunlap and King Kelly. He then spent the winter in Providence and supposedly married around this time; it was a common mistake as he actually just lived with his girlfriend.

Radbourn was still going strong in 1887, hurling in 50 games for a 24-23 record. His dominance was clearly waning though as evidenced by his mere 87 strikeouts. After doing so every year prior, he wouldn’t fan 100 batters again. Some of this had to do with the shrinking of the pitcher’s box by 18 inches prior to the season, effectively pushing the pitcher farther from the plate. Rad also liked to move around in the box as much as possible and took full advantage of every inch to intensify his delivery. His meager strikeout total in 1887 can also be explained by the fact that for that year only four strikes were required to retire a batter. His innings pitched would drop significantly after ’87 as well. Through his first seven years in the majors, Radbourn amassed 3,481 innings, an average of nearly 500 per year. He would average about half that over his final four seasons. For some reason, Rad rarely used his famed drop ball in 1887. By August, he was openly discussing going into business in Bloomington and retiring from baseball.

The year ended on a sour note. On September 6, Rad lost 10-4 to Philadelphia. He walked five batters and bounced a wild pitch in the first inning. In total, he had seven base on balls, two wild pitches, two errors and hit two batters. At the time, the club only stood 7 1/2 games out of first place, but there were four tough teams higher in the standings. The Boston only had three more home games remaining and then would spend a month on the road to end the season. The club was headed for a western swing and Soden didn’t feel the need to pay the travel expenses of a lackluster pitcher, in his opinion that is. So, he suspended Radbourn for “careless and slovenly play” or as another newspaper put it, “chronic poor play.”26 Soden made his announcement: “We have been played for flats long enough. Radbourn is paid over $600 a month to play ball. That sum ought to be enough to make him keep in condition to pitch good ball. I do not know whether it is poor condition, unwillingness, or what it is. But he has been doing the very worst of work. Today’s game was the culmination point. If he cannot do any better work than he has done recently, he is not worth what we pay him.”27 Soden even went so far as to declare that the fans demanded the action, which was an obvious falsehood. It is true that Radbourn hadn’t been shining in the box; he was 2-5 in his last seven starts. Of course, a suspension would also save the club the salary that Soden spoke of.

The suspension lasted 10 days before Soden relented on the 15th and summoned the pitcher to meet the club in Pittsburgh. Rad was none too happy to find his paycheck docked $200 for the time off. In November, Soden publicly offered Radbourn a mere $2,000 for 1888 with an incentive clause offering $100 for each victory. The pitcher cut off contact with the club, openly stating, “They have driven me out of the business. You will never see me in another game of ball.”28 The statement seemed all the more final when word leaked of a business opportunity.

In January 1888, he purchased a half-interest in a saloon and billiards pallor at 214 W. Washington Street beneath the Windsor Hotel, the largest hotel in Bloomington, renaming it Radbourn’s Place; over the years, it attracted a great many sports fans. At the time it appeared that he would quit the game. The Daily Inter Ocean chimed in with its assessment of Rad’s remaining potential on the diamond: “…his days of usefulness are about at an end. Radbourne’s (sic) effectiveness lies in his command of the ball. He formerly brought the ball from over his head, but has given it up entirely, as it injures his arm.”29 Note another indication that indeed Radbourn threw the ball overhand at times, seemingly during the brief period between 1884 and ‘87.

The fact is Radbourn was still a useful pitcher and had been through this time an innings eater. The Boston club needed him to complement John Clarkson on the mound. April came and still no one heard from Rad. In the middle of the month, Soden declared, “We have heard absolutely nothing from Radbourne (sic). So far as we know he is still in Illinois and may remain there.”30 Boston management, known as the Triumvirs, was equally as stubborn, demanding that the pitcher join the club or face blacklisting by May 1. Behind the scenes though, the club was capitulating. They matched his salary from 1887, $4,800 and returned the $200 under contention. On April 17, Radbourn agreed to rejoin the team. On the 18th, he played first base for the local Bloomington club in an exhibition game against the St. Louis Whites, a Chris von der Ahe owned club. He wore his Boston uniform and went 3-for-4. That spring, he imparted some of his expertise onto a young Bloomington pitcher named Clark Griffith. Griffith in turn used every trick that Rad taught him and developed a few of his own to build a fine pitching career for a man standing only 5-foot-6 without a dominant fastball.

Boston fans and especially his teammates were thrilled to have Rad back. The club held a ceremony upon his arrival and gave him a gold-headed cane in appreciation with the inscription, “Presented to Charles Radbourn by the Boston Baseball Club, May 11th, 1888.” On the 16th, he pitched his first game, a 2-1 win over Chicago. On June 27, he allowed only one hit in a 13-0 shutout of Washington. Radbourn’s showing in ’88 wasn’t a success by any measure though. In 24 games he won only seven of 23 decisions. In December, he signed for another season in Boston.

Radbourn rebounded in 1889 to post a solid 20-11 record in 33 games. The year was contentious though. He had always had an issue with management and their dominance in player relations during the era. In truth, he had a problem with authority figures, managers, owners and umpires. He saw himself as a victim of the reserve clause, knowing full well that he would have made substantially more money if allowed to play in New York during his Providence days. He also felt the wrath of management in their indiscriminate use of suspensions and threat of blacklisting. In short, he was acclaimed as one of the top pitchers in the game, perhaps the greatest of the nineteenth century, and he was still treated poorly, in his opinion, by the businessmen that ran the game. In truth, that opinion wasn’t far from the reality. Arthur Soden, for one, had little use for ballplayers outside their production. He firmly believed that labor served only one purpose — results – and had no use for the complications that employing human beings engendered. As a result, Radbourn was a strong supporter of Monte Ward’s players union, the Brotherhood of Professional Baseball Players.

On November 13, Rad departed on a barnstorming tour with many of his Boston teammates organized by Chicago executive Jim Hart. He was one of the three pitchers along with Clarkson and Hugh Daily. King Kelly met the men in San Francisco. The union with some financial backers had established the Players League, which would operate as a third major league in 1890. Kelly was placed in charge of the new Boston franchise. He signed quite a few of the men to Players League contracts by the end of the year including Radbourn. On January 6, Rad left the west coast free from National League control. The Boston club, led by Kelly, Radbourn and Dan Brouthers captured the pennant by 6 1/2 games over Brooklyn. Rad chipped in a 27-12 record in 41 games, his most since ’87. The season Radbourn became universally referred to as “Old Hoss” by the newsmen was 1887. The nickname, denoting his status as his team’s workhorse, may have been used before this by his teammates.

Unfortunately, the Players League only lasted one season. Radbourn stuck with King Kelly who was hired to oversee the Boston club in the American Association. Kelly was then put in charge of a new Cincinnati franchise in the AA. He quickly sped off on a recruiting trip, stopping in Bloomington to ink Radbourn. Kelly left after signing the pitcher but received a shock when Rad signed with the National League Cincinnati entry on April 10. He was wooed by manager Tom Loftus, his first professional skipper back with Peoria, for $5,000 and a promise that he didn’t have to pitch on Sundays. He was promptly blacklisted by the AA, which was of no consequence since it was in its final season anyway.

Radbourn was shelled in his first outing on April 25, one of his worst performances as a professional. He lost 23-7 to Cleveland, ceding 26 hits and 6 walks. By July, Rad was seriously contemplating retirement. He took his turn in the rotation until August 11 which proved to be his last major-league appearance. That day, he gave up 15 hits in an 8-6 loss to Brooklyn. For the season, he produced an 11-13 record over 26 games pitched. For his career, Radbourn completed 489 of his 503 starts for a 309-195 won-loss record which included 35 shutouts. He tossed a no-hitter and seven one-hitters, still a record for National League pitchers. Versatile, he also appeared in the outfield in 118 games and in the infield another 32 times. In nearly 2,500 at-bats, he hit .235 with 259 RBIs.

Rad asked for and was granted his release on August 23. Cincinnati signed Ed Crane as his replacement. Old Hoss officially retired at age 36 to tend to his saloon. There are some indications that Cincinnati was reneging on his salary payments which may have hastened his departure. At the time of his retirement, he was said to be worth $25,000 in real estate and bank stocks, a significant sum for the era. The money allowed him to spend much of his time away from the office. He spent countless hours hunting and fishing, passions he had indulged since childhood. He was skilled with a rifle by an early age and was a renowned field shooter as an adult, once issuing an open $1,000 challenge to the any and all comers, even national champions. Rad kept a kennel of “thoroughbred pointers” that honed their skills on long hunting trips.

He lived with his longtime girlfriend Carrie Stanhope whom he met during his time in Providence. Her maiden name was Clark and she had previously been married to Providence resident Charles Stanhope. The couple had a son, Charles Jr., born in 1875. The Stanhopes were separated by 1880; thus, Rad was not involved in their marital difficulties. Carrie, two years younger than Radbourn, was born in Ireland. Mother and son left Providence for good with Rad after the Grays’ franchise folded. She assisted in the running of the Bloomington saloon, especially so after Radbourn’s hunting accident. After his death, Radbourn’s parents and seven siblings contested her claim to his estate. They were apparently unaware that Radbourn and Stanhope eventually did marry — on January 16, 1895 in Boston. The couple didn’t have any children of their own.

A little bored, Radbourn considered coming out of retirement in 1893, but priced himself out of the market. The next season, he was a little more serious. He contacted at least six managers including Chicago, Washington, Boston, St. Louis, and New York stating that he was in excellent condition and ready to pitch. No major-league club jumped at the opportunity so he signed with King Kelly’s Allentown Colts, popularly known as Kelly’s Killers, in the Pennsylvania State League. The team also included Mark Baldwin, Pete Browning, Mike Kilroy, Ted Larkin, and Sam Wise. The potential comeback ended before it began.

On April 13, 1894, Rad was accidentally shot in the face by a friend while hunting. He had stepped from behind a tree when his friend fired a shotgun. Radbourn lost sight in his left eye and received considerable damage to his face, including partial paralysis and some speech loss. Once a big, strong, good-looking athlete, his disfigurement weighed on him the rest of his life. Similar accidents weren’t all that uncommon. Back in 1879, Rad’s brother William shot himself in the left side and in both hands while hunting.

The ex-pitcher’s waning years were unpleasant. Because of his face and ill-health, he became somewhat of a recluse at his apartment. He suffered from the effects of the paresis of the eye and other ailments and drank heavily. During at least his last year, Radbourn had severe cognitive troubles, perhaps brain damage from syphilis. He was also subject to convulsions and abnormalities with his nervous system. In 1895, it was falsely rumored to be dying of tuberculosis. He was ill though. As the Boston Globe described in December 1896, “Charley Radbourn…is now at his old home in Bloomington, Ill., a wreck of his former self, owing to sickness.”31 As his obituary in the local Bloomington Pantagraph described, he “…grew sick, lingered on from year to year as disease gnawed at his mental and physical being, robbing him of speech, feeling and locomotion long before the final day arrived.”32 The Brooklyn Eagle claimed that “his brain has been affected more or less for about a year.”33

On February 3, 1897, Radbourn suffered another convulsion which ultimately left him in a comatose state. He never woke up, dying at age 42 around 2 PM two days later at his residence in the Windsor Hotel. He was buried at Evergreen Memorial Cemetery in Bloomington. The local newspaper kindly described him as “a great favorite in Bloomington. He was a sociable, humorous, good-natured man, and a charming story teller.”34 In 1939, he was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in his proper slot among the first group of inductees.

An updated version of this biography is included in “20-Game Losers” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Emmet R. Nowlin.

Sources

Special thanks for a valuable exchange of emails with Edward Achorn, author of Fifty-Nine in ’84: Old Hoss Radbourn, Barehanded Baseball and the Greatest Season a Pitcher Ever Had.

Archivist/Librarian Bill Kemp at the McLean County Museum of History was especially helpful; in gathering information for this article, as was colleague Rochelle Gridley.

Bob LeMoine was of great help in tracking down citations to help document quotations in the original biography.

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted:

Bell, David, The Nineteenth Century Transaction Register, SABR

Browning, Reed. Cy Young: A Baseball Life (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2000).

Ivor-Campbell, Frederick, Robert L. Tiemann and Mark Rucker. Baseball’s First Stars (Cleveland: The Society for American Baseball Research, 1996).

Kahn, Roger. The Head Game: Baseball Seen from the Pitcher’s Mound (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2001).

Leitner, Irving A. Diamond in the Rough (New York: Criterion Books, 1972).

Spatz, Lyle, ed. Society for American Baseball Research. The SABR Baseball List and Record Book New York: Scribners, 2007).

Kemp, Bill, “Famed 19th Century Ballplayer ‘Old Hoss’ Came from Bloomington,” Pantagraph.com, April 6, 2008.

Ancestry.com, Baseball-reference.com, Retrosheet.org, and the following newspapers: Alton (Illinois) Telegraph, Atchison (Kansas) Daily Globe, Bismarck Daily Tribune, Cincinnati Enquirer, Daily Bulletin (Bloomington, Illinois), Daily Evening Bulletin (San Francisco), Daily Iowa Capital, Daily Miner (Reno, Nevada), Daily Nebraska State Journal, Daily Northwestern (Oshkosh, Wisconsin), Daily Republican-Sentinel (Milwaukee), Decatur Daily Republican, Decatur Review, Dubuque Herald, Evening Gazette (Sterling, Illinois),

Fitchburg (Massachusetts) Sentinel, Hamilton (Ohio) Daily Democrat, Hartford Courant, Iowa State Reporter, Janesville (Wisconsin) Gazette, Lincoln (Nebraska) Evening News,

Logansport (Indiana) Journal, Logansport Pharos, Los Angeles Times, Milwaukee Journal, Newport (Rhode Island) Daily News, New York World, Oakland Tribune, Penny Press, (Minneapolis), Rocky Mountain News, San Antonio Light, Spirit Lake (Iowa) Beacon, Sporting Life, The Sporting News, St. Louis Exchange, St. Paul Daily News, and the Weekly Gazette and Stockman (Reno, Nevada).

Notes

1 E.E. Pierson, “‘Old Hoss’ Radbourne: The Famous Old Time Veteran Who Pitched Seventy-Two Games in a Single Season,” Baseball Magazine, Vol.19 Issue 4 (August, 1917):423-424.

2 Bloomington Pantagraph, September 2, 1876: 3.

3 Ibid.

4 Per Archivist/Librarian Bill Kemp at the McLean County Museum of History.

5 E. E. Pierson, “’Old Hoss’ Radbourn,” Baseball Magazine, Vol. 19, Issue 4 (1917): 423.

6 Ibid.

7 Bloomington Daily Pantagraph, January 9, 1880: 3.

8 Alfred H. Spink, The National Game: A History of Baseball, America’s Leading Outdoor Sport, From the Time it was First played up to the Present Day, With Illustrations and Biographical Sketches. (St. Louis: National Game Pub, 1911), 150, 152; Bill James and Rob Neyer, The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers: An Historical Compendium of Pitching, Pitchers, and Pitches (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2004), 349-350.

9 Cleveland Herald, date unknown.

10 Topeka State Journal, May 1, 1891: 7.

11 Milwaukee Sentinel, date unknown.

12 “Outdoor Amusements,” Washington Post, May 6, 1883: 8.

13 Cleveland Herald, date unknown.

14 Providence Journal, July 14, 1884.

15 “One More Victory for the Boston Club,” Boston Advertiser, July 17, 1884: 8.

16 “A Good Clean Lead,” Boston Globe, July 17, 1884: 4.

17 Ibid.

18 “Radbourne’s [sic] Twirling Feat is Still Unrivaled; Won 63 Games and N.L. Pennant, 37 Years Ago,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 13, 1921:9.

19 “Old Providence Manager Tells Inside History of Old Hoss Radbourn Winning 26 out of 27 Games,” New Castle Herald (Pennsylvania), July 7, 1908:2.

20 “The Baseball Field,” New York Times, October 24, 1884: 2.

21 Ibid.

22 “No Deserters Wanted Back,” New York Times, November 20, 1884:5.

23 “Notes of the Game,” New York Times, September 13, 1885: 2.

24 Ibid.

25 “Notes of the Game,” New York Times, September 24, 1885: 2.

26 Tyrone Daily Herald (Pennsylvania), September 9, 1887:1; “Base Ball Notes,” Indianapolis News, September 7, 1887:3.

27 “Radbourn Indefinitely Suspended,” Hartford Courant, September 7, 1887: 1.

28 “The Sporting World,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, January 7, 1988: 5.

29 “Bat and Ball,” Daily Inter Ocean (Chicago), January 2, 1888: Section 2: 12.

30 “Soden and Radbourne,” Inter Ocean, April 18, 1888:2.

31 “Baseball Notes,” Boston Globe, December 21, 1896: 7.

32 Daily Pantagraph, February 6, 1897: 7.

33 “Hurst and the Rules,” Brooklyn Eagle, February 5, 1897: 10.

34 Bloomington Pantagraph, date unknown.

Full Name

Charles Gardner Radbourn

Born

December 11, 1854 at Rochester, NY (USA)

Died

February 5, 1897 at Bloomington, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.