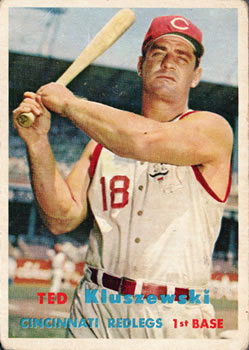

Ted Kluszewski

The area known as Argo is located eight miles west of Chicago’s old Comiskey Park in Summit, Illinois, a lowdown five-figure village in Cook County known for a corn milling and processing plant that is among the largest of its kind – and has the odor to prove it. It was also home to Ted “Klu” Kluszewski, the 6-foot-2, 225-pound mountain of a man with the famous 15-inch biceps, whose legend in baseball history will live even longer and go farther than the home runs he hit decades ago.

The area known as Argo is located eight miles west of Chicago’s old Comiskey Park in Summit, Illinois, a lowdown five-figure village in Cook County known for a corn milling and processing plant that is among the largest of its kind – and has the odor to prove it. It was also home to Ted “Klu” Kluszewski, the 6-foot-2, 225-pound mountain of a man with the famous 15-inch biceps, whose legend in baseball history will live even longer and go farther than the home runs he hit decades ago.

Kluszewski has often been referred to as one of the most underappreciated players of the post-World War II era; one whose accomplishments as a player and a coach have remained under the radar far too long. In the mid-1950s “Klu” was the original “Big Red Machine,” a long-ball hitter and run-producer without peer. In the four seasons from 1953 to 1956, he averaged 179 hits, 43 homers, and 116 RBIs, numbers every bit as impressive as those of Eddie Mathews (152-41-109) of the Milwaukee Braves and Duke Snider (180-42-123) of the Brooklyn Dodgers in the same period. It’s not a stretch to believe that if Kluszewski had stayed healthy and productive for four or five more seasons, he would have joined Mathews and Snider in the Hall of Fame. Despite an abbreviated career, his 251 homers while he was with rank fifth on the Reds’ all-time list.

Born on September 10, 1924, Theodore Bernard Kluszewski attended Argo High School in Summit, where he excelled in football. His father worked in a local factory. As a youth, Klu’s baseball experience consisted mostly of sandlot games. Indiana University recruited him primarily as a football player, but he also played baseball there, and his 1945 season ranks as one of the best for a two-sport athlete in the school’s history. As a center fielder, Kluszewski hit .443, a school record that stood for 50 years; then the star end and kicker helped lead the Hoosiers to their only outright Big Ten football championship. The squad, which also included future NFL players Pete Pihos and George Taliaferro, finished with a 9-0-1 mark, the only unbeaten Hoosiers football team.

If not for World War II, Kluszewski most likely would have embarked on a professional football career. During that time the Reds held spring training at the Indiana campus in Bloomington because major-league teams were forbidden to train in the South. One day they invited the kid to take some hacks at batting practice. As legend has it, “Big Klu” promptly launched a few rockets over an embankment nearly 400 feet away. After they picked up their jaws off the ground, team officials offered him a $15,000 contract, which he accepted.

With the bonus in hand, Kluszewski married Eleanor Guckel in February 1946. Eleanor was a fine athlete herself, excelling at softball, and Klu later credited her with helping his major-league career by taking films of him at bat and in the field from seats close to the field.

Making his professional debut for the Reds’ Columbia (South Carolina) farm team in the Class-A South Atlantic League in 1946, Kluszewski was an immediate sensation, leading the league with a .352 batting average and driving in 87 runs in 90 games. He made his Cincinnati debut in April 1947, but logged only 10 at-bats with the Reds, spending most of the season with Memphis of the Double-A Southern Association. Again he tore up the league, winning the batting crown with a .377 average.

In 1948 Kluszewski returned to Cincinnati to stay for 10 full seasons. It wasn’t long before his large biceps prompted Klu to cut off the sleeves of his jersey, one of the boldest fashion statements in baseball history. At first, he did it because the sleeves were restricting his swing, but after a while it became part of his persona. “I remember the first time that I saw Ted in those cut-off sleeves,” former White Sox teammate Billy Pierce said of his trademark style nearly a half-century later. “They were good-sized. He was a big man. A big man.”1

Despite those massive arms, Kluszewski did not immediately become a home-run hitter at the major-league level. He hit only 12 as a rookie in 1948, and just eight in 1949, though he showed overall improvement as a hitter by lifting his batting average 35 points from .274 to .309. He showed his power potential for the first time in 1950, hitting 25 home runs and driving in 111 runs to go along with a .307 batting average. After a dip in 1951 (.259-13-77), Klu had 16 home runs in 1952 while raising his average to .320. His big breakthrough came a year later.

In 1953 Kluszewski finally blossomed as big-time slugger, as his .316 batting average, 40 home runs, and 108 RBIs translated into a seventh-place finish in the Most Valuable Player vote. A career year followed in 1954, when he led the NL with 49 home runs. He hit .326 (fifth overall), slugged .642 (third), drove home 141 runs (first), and finished a close second to New York Giants outfielder Willie Mays in the MVP vote. In the All-Star Game at Cleveland, he delivered an RBI single and a two-run homer in consecutive innings, the latter of which broke a 5-5 tie in an eventual 11-9 loss. Klu was at his best when the stars came out, as he hit .500 in four midsummer classics.

Kluszewski did the brunt of his damage at the cozy confines of Crosley Field, which produced one of the highest home-run rates of the decade, but he wasn’t known for front-row jobs. What separated Kluszewski from the rest of the musclemen was his off-the-charts discipline at the plate. He totaled 31 fewer strikeouts (140) than home runs (171) in his four peak seasons. Of the ten times in major-league history that a player hit at least 40 homers with fewer strikeouts, three were by Kluszewski. The others on the list: Lou Gehrig (twice), Johnny Mize (twice), Mel Ott, Joe DiMaggio, and Barry Bonds.

“Everybody moves at his own pace,” Billy Pierce said many years later. “I mean, we had a Nellie Fox who jumped around all the time. Sherm Lollar couldn’t move very fast no matter what happened. But both gave you everything they had on the field and Ted was the same way. He worked at his own pace, and he had a pretty good career that way.”2

Kluszewski didn’t make many mistakes in the field, either, although his detractors argued that the low error totals were the result of an inability or reluctance to move more than one step either way. If you believe in range factors, though, Big Klu was well above average in this regard before his achy back came into play. He led the league in fielding percentage in a record five consecutive seasons, largely the result of excellent hands and nimble footwork.

“Everybody knows Ted could hit a baseball,” said the late Bill “Moose” Skowron, the former New York Yankees first baseman who crossed paths with Big Klu many times in their careers. “What some people don’t know is that he was a hell of a first baseman and a hell of a nice guy, too. And he always played in those short-sleeve shirts. He was built like a rock, you know.”3

Kluszewski might have had a long run as one of baseball’s top sluggers if not for a back injury that resulted from a clubhouse scuffle during the 1956 season. The disc problem proved to be Delilah to Klu’s Samson, as he would never be the same power hitter again. After the 1957 season, one in which Klu was limited to a half-dozen homers and 21 RBIs in 69 games, he was dealt by the Reds to Pittsburgh in return for Dee Fondy, another veteran first baseman.

In 1958, his only full season with the Pirates, Kluszewski produced a mere four home runs and 37 RBIs in 100 games, but he had a positive influence on a young, talented team that was on the move. Before he left, Klu made history at Forbes Field on May 9, when he went deep against Philadelphia Phillies pitcher Robin Roberts leading off the 12th inning, the 19th walk-off homer to decide a 1-0 game since the turn of the century.

Big Klu began the 1959 season with the Pirates, but was reduced to part-time status behind Dick Stuart and Rocky Nelson. He had started only 20 games and logged just 122 at-bats by late August when the White Sox, looking to add power for the stretch and (hopefully) the World Series, traded outfielder Harry “Suitcase” Simpson and minor-league pitcher Bob Sagers for Kluszewski on August 25.

While the 34-year-old Kluszewski was deep into the back nine of his career at the time, news of his return to Chicago was well received by South Siders. “Certainly, the attitude of the fans was positive about the trade,” said John Kuenster, who covered the 1959 pennant-winners as a Chicago Daily News beat writer. “Ted was a nice guy, a popular guy. He was well known in the area and his return was very well received there.”4 At the very least, the consensus went, Klu could do no worse at the position than 35-year-old warhorse Earl Torgeson, a .226 hitter at the time, or 24-year-young prospect Norm Cash, a .231 hitter who was new to the pressure of a pennant race.

Besides, the righty-dominated lineup had been rather “Kluless” for months. The veteran lefty provided a much-needed option for a “Go-Go” Sox team that was overly dependent on speed and defense at the time. “We didn’t have a regular first baseman,” Pierce recalled. “When we got Ted, we all thought it was a very, very good thing for us, because he gave us a strong left-handed hitter with a good reputation. We never thought he was past his prime but that he would help us. We were very glad to have him on our ballclub.”5

What Kluszewski lacked in glitzy numbers, he made up for in stature. His mere physical presence gave the Second City a sliver of security, a reason to flex its own muscles for a change. “Ted was a quiet fellow, but he had been with a winner in Cincinnati and had many accomplishments in his career,” Pierce said. “A fellow like that is a kind of automatic leader on the team. He gave us stability, which was very good for us.”6

As it turned out, Kluszewski didn’t quite turn back the clock in the final weeks of the regular season, but he had his moments. The most significant took place in Chicago on September 7, when the White Sox defeated the Kansas City Athletics in a Labor Day doubleheader. In the opener Kluszewski contributed a key run-scoring hit in a 2-1 victory; in the nightcap he slugged a pair of homers and drove home five runs in a 13-7 rout. As a result of the sweep, the White Sox maintained a 4½-game lead over the second-place Cleveland Indians, who scored an emotional sweep of the Detroit Tigers by 15-14 and 6-5 scores the same day.

While Kluszewski had rather modest statistics in the final 32 games of the regular season – .297 batting average, 2 homers, 10 RBIs – the hidden numbers suggest the White Sox were deeper and better because of him. “Ted was a great asset for us,” Pierce said. “He was an important cog in the middle of the lineup.”7 With Klu as protection in the cleanup spot, outfielder Jim Landis immediately picked up the pace in the third hole. The offense produced more runs (4.5 vs. 4.3 per game) and team won at a higher rate (.625-.607) with Big Klu than without him.

But it was his performance in the 1959 World Series against the Dodgers that made South Side fans forever remember the Kluszewski trade as one of the greatest Brinks jobs in White Sox history; a local boy who made very, very good one unforgettable season. In the six World Series games, Kluszewski hit .391, slugged three home runs and drove in 10 runs. His 1.266 OPS (on base plus slugging) was just plain silly.

Kluszewski smashed two home runs in an 11-0 rout of the Los Angeles Dodgers in the Series opener. “Oh, man, the two home runs that Ted hit…,” Pierce smiled at the thought of them. “That was exciting. I mean, there we were in the World Series. … The fans were excited, we were excited, everybody was excited.”8 Witnesses said Comiskey Park never rocked the way it did in the moments after Kluszewski took reliever Chuck Churn for a ride to the upper deck in the fourth inning. The two-run blow not only sealed the victory, but it did much to “chuck” Churn, as it turned out. The pitch was his last in the big leagues.

Until outfielder Scott Podsednik went deep to decide Game One of the 2005 World Series, the monster blast stood as the most memorable home run in team history. “There was a similar feeling with the two home runs,” said John Kuenster. “They gave White Sox fans a reason to think, ‘Maybe we will win this thing after all,’ although in the case of the 1959 team, it didn’t turn out that way.”9 Alas, the Dodgers won four of the next five games to become world champions.

Kluszewski left the team for the Los Angeles Angels in the expansion draft after the 1960 season – he had hit .293 with 5 homers in 81 games – but not before he was involved in the most controversial play of the 1960 campaign. In a game at Baltimore on August 28, Kluszewski hit a dramatic pinch-hit, three-run homer against Orioles starter Milt Pappas in the eighth inning to give his team a 4-3 lead. Or so it seemed. The umpire crew agreed that time had been called before the pitch was thrown and the home run was wiped out. After teammate Nellie Fox was ejected from the game, Kluszewski flied out to end the threat. The White Sox went on to drop a 3-1 decision and fell three games out of first place.

Before Kluszewski retired one year later, he exacted a sliver of payback at the same site. In the first game in Los Angeles Angels history, Big Klu took Pappas deep with a man on base in the first inning, the first home run in franchise history. One inning later he greeted rookie John Papa with a three-run homer to set the wheels in motion for a 7-2 victory. Kluszewski finished his final big-league season with a .243 batting average, 15 home runs, and 39 RBIs in 107 games.

Kluszewski returned to the Reds after retiring as a player, and his impact on the team was no small one. He was the Reds’ hitting coach for nine seasons in the 1970s, a decade that the Big Red Machine dominated as few other offenses in NL history had done. In 1986, after he had become a hitting instructor in the Reds’ minor-league system, Kluszewski suffered a heart attack and underwent emergency bypass surgery. On March 29, 1988, a massive heart attack took his life. He was 63 years old.

That the funeral service in suburban Cincinnati was a virtual Who’s Who said as much about Kluszewski the person as Big Klu the athlete. Rose, Johnny Bench, and Tony Perez were among those who paid their respects. Stan Musial and Joe Nuxhall did, too. During the 1988 season the Reds wore black armbands in memory of their late teammate. There wasn’t an arm large enough to do justice to Big Klu, a big man in more ways than one.

An earlier version of this biography originally appeared in SABR’s “Go-Go To Glory: The 1959 Chicago White Sox” (ACTA, 2009), edited by Don Zminda, and “Time for Expansion Baseball” (SABR, 2018), edited by Maxwell Kates and Bill Nowlin.

Notes

1 Billy Pierce, interview with author, August 2008.

2 Ibid.

3 Bill Skowron, interview with author, August 2008.

4 John Kuenster, interview with author, September 2008.

5 Pierce.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Kuenster.

Full Name

Theodore Bernard Kluszewski

Born

September 10, 1924 at Argo, IL (USA)

Died

March 29, 1988 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.